Sally McGregor was a newly trained physician when she moved to Jamaica in 1965 from England for what she called a one-year “adventure.” She ended up marrying and staying 35 years. It’s a good thing she did. The impact evaluation of a program she designed to improve the development of chronically malnourished toddlers in Jamaica is changing how the development world views – and tries to improve – the problems faced by disadvantaged children all over the world.

The Jamaica study, as it’s known, sent trained health workers into poor and disadvantaged households in Jamaica’s capital Kingston to teach mothers how to stimulate their toddlers by playing, talking and praising them. Some children also received nutritional supplements. Both groups were compared with similarly disadvantaged children who received only supplements, or nothing. Twenty years later, a follow-up study led by economist Paul Gertler and nutritionist Sue Walker – and supported by the World Bank’s SIEF impact evaluation trust fund-- found that children who received extra stimulation, whether with nutritional supplements or not, had more years of college and were earning 25% more money than similarly stunted babies whose mothers received just nutritional supplements or no intervention. The 25% earnings boost put them on the same level as their non-stunted peers – a sign that early intervention isn’t just good for children, but it’s an economic gain for the country.

The findings are now the basis for early childhood development (ECD) programs and ongoing impact evaluations around the world. McGregor recently took the time to talk about what the Jamaica study has taught the development world, what’s still not known and why not all picture books are equal when it comes to teaching kids.

Q.What sparked your interest in ECD all those years ago?

When I got married and had young children, I didn’t want to work nights and weekends, so I went into research at the University of the West Indies. As part of my research, I tracked the development of 300 children born in Kingston. These were children I knew because when I was working as a doctor, I saw them regularly in the hospital during their infant check-ups. Their development had been fine when they were babies, but not when they were toddlers, and they had deteriorated. When I went to their homes, I saw that they weren’t getting the right stimulation.

Q.What does ‘right stimulation’ mean?

The children were doing nothing. They had no toys or books. The whole family lived in one room and kids often slept under beds if there wasn’t room on the bed. I saw that mothers, depending on their own socio-economic background, interacted with their children very differently when it came to playing a sorting game. The educated middle class women were naming concepts as they played, explaining to their children what goes where and why. The poor women just watched their children try to sort the toys and just kept saying ‘no, no, no’ when the child sorted incorrectly. The difference was phenomenal.

Q.Where did you get the idea of using play to try to give children a development boost?

At that time, the Head Start Program in the U.S. was reporting long-term benefits, which encouraged me to think about the issue of how to give poor children extra stimulation. A center-based program, like Head Start, where people with Masters degrees were playing with children, wasn’t feasible for developing countries. But I wondered if it could be adapted. People said home-based interventions wouldn’t work in Jamaica because the homes were so bad and the mothers were barely literate. But some common sense and the reading I had done gave me ideas.

Q.What did people think about your research at first?

I had a very hard time when I started. My husband used to say, “When will you be a proper doctor and stop messing around with toys?” People told me that child development couldn’t be measured and that it was a “soft science.” Looking back, it was quite a battle.

Q.Did you ever start to doubt the program?

At 7 years old, the children who received the stimulation were doing only slightly better on the measurements of their cognitive, emotional and psycho-social skills, and it looked like all the positive effects were washing out. I had hoped the effects would be sustained, but I wasn’t expecting it: the homes were so bad and the schools were not particularly good either. By age 12, though, the results were encouraging: IQs were up and the kids looked better. This was even better at age 17. I didn’t expect to do a follow up so quickly after that, but then Paul Gertler approached Sue Walker and me wanting to look at the economic situation of the children.

Q.Is the Jamaica study the answer to improving children’s development?

The fact is, while we know a great deal about the importance of early childhood interventions for poor families, we actually don’t know whether the Jamaica model’s results are replicable. There are important differences between Jamaica and some other countries trying similar programs. For instance, in Jamaica, most of our kids went to nursery school. The schools weren’t very good, but having them attend some kind of basic school helped. Nutrition throughout Jamaica also improved. We have had benefits in trials in Bangladesh and Colombia, but we don’t know if they are sustainable.

Q.What’s been the impact of the study outside of Jamaica?

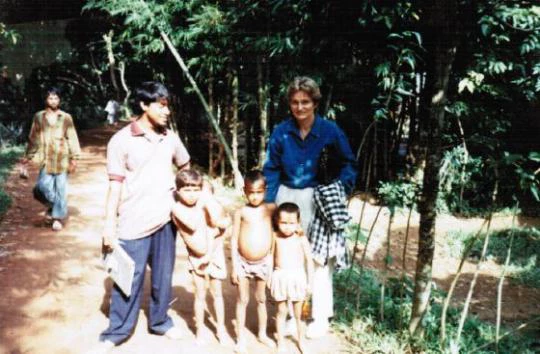

The great news is that the results have led to programs in many countries that are testing whether this works in their specific context. In some cases, former Ph.D. students I trained such as Jena Hamadani are working on projects elsewhere. In other cases, it’s ad hoc. People read about the work we’re doing, come to me and say “Can you help me?” Sue Walker and the Jamaican team got funding from Grand Challenges Canada to put all the training materials, with videos and curriculum, on the web and assist at least three countries in launching it.

Q.Are the programs tailored to fit different country contexts?

Yes. For every country, we translate to the local language, redraw the illustrations, and look at the environment children are living in so that all the books and pictures reflect their lives, ethnic origin and family structure. For example, we won’t include animals that the children won’t see around them. We also include local games and songs and modify pretend games to reflect their experiences.

Q.The Jamaica study involved expensive home visits. Are you working on testing less expensive models?

That is a big challenge. When we first started, we were visiting once a week, which at the time was considered ridiculously little in terms of an intervention. Now, programs are being tested with less input to make them even less expensive. Some models have mothers bringing their babies into clinics, instead of home visits, which is another cost-saving measure. In general, programs are trying to reach more people for less effort, and that is a concern. There must be a minimum level of inputs to be effective.

Q.What continues to be your biggest challenge?

A lot more money goes into nutrition programs than into stimulation. Funders put money into malnourishment because they want to save lives, but as I see it, if you have a disease, they are only treating some of the symptoms.

Q.Were you surprised at the attention the study received after the latest results pointing to increases in earnings for these now-young adults?

Economists helped spread the word when they got involved and added the spin of investment and cost effectiveness. Early childhood stimulation is in vogue now—no doubt about it. We’ve finally come out of the wilderness—it’s just a shame I’m so old. I’d love to go to all these places around the world to help train people. I plan to go on assisting where I can but depend on the Jamaican team and other collaborators I have worked with to continue spreading the idea.

Follow the World Bank education team on Twitter: @WBG_Education

Join the Conversation