The first major trend is an increase in individual empowerment, stemming from declines in poverty, the growth of a global middle class and more widely available communications and other technologies. Second, power will become more diffuse across countries, as emerging markets grow rapidly and many rich countries age and grow sluggishly. Third, demographic changes will take place slowly but inexorably. The world population will continue to rise rapidly and reach 8.3 billion in 2030 mainly on account of increased life expectancy in developing countries despite declining fertility. While some countries will “shrink” (such as Germany) others, like Kenya, will experience significant youth bulges, and rapid urbanization. Finally, as populations grow and increased consumption levels strain existing resources, access to food, energy, and water will become ever more crucial.

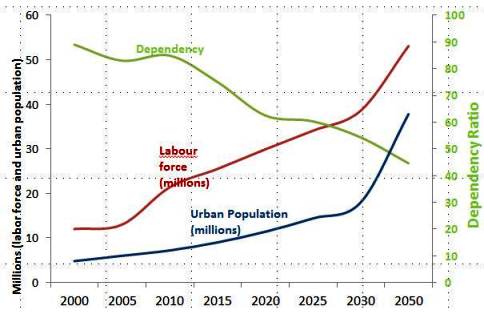

So how will the global megatrends play out in the Kenyan context? The 2030 horizon also has a special meaning for Kenya’s economic development, not least because its own development strategy is anchored in Vision 2030, Kenya’s aspiration to become a vibrant middle-income economy in the next 17 years. In line with global trends, Kenya will have many more people who will live longer, choose to reside in urban areas and benefit from more and better education. If current trends continue, Kenya will have 63 million people, about the same as the UK today. The country’s workforce will almost double: from 21 million today to about 39 million while the number of dependents (children and elderly) will grow much more slowly. In other words: the “dependency ratio” (dependents divided by workforce) will decline dramatically (see figure).

Figure: Kenya’s big transitions: Demography and geography

Source: World Bank projections

With these big transitions come better economic opportunities, which Kenya has yet to leverage. In other parts of the world, a rising workforce and urbanization have been synonymous with significant and rapid productivity gains and poverty reduction. With more workers and customers, companies are able to produce at scale with lower costs. The East Asian miracle describes a process of rapid industrial expansion which Kenya has not yet experienced. Over the last decade, the share of manufacturing in Kenya’s GDP stayed constant at around 10 percent. In 2000, manufacturing was still the second largest sector in the economy (behind agriculture), but now it is fourth, overtaken by transport and communications as well as wholesale and retail trade. Yet, in other parts of the world manufacturing has proven to be the most effective way to offer jobs to bulging youth populations.

In the social sectors these mega transitions will be underpinned by more complex development issues, which will increase further with an urbanizing and aging population. In education, service provision will shift from quantity to quality. In the health sector, Kenya is experiencing a dual disease burden: communicable diseases, such as malaria, diarrhea and AIDS, are still weighing on the country’s health system, while non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, high blood-pressure and cancer are emerging, presenting new challenges and higher costs to the health system.

These development challenges require the “second generation” of reforms. These are more complex because they no longer involve ‘brick and mortar’ development, but rely heavily on improving the quality of public institutions. The reform objectives include raising the quality of education and reducing child and maternal mortality, areas where other middle-income economies are also struggling.

By 2030, the world may have completed its shift away from the West and (back) to the East as well as from the North to the South. But this isn’t the zero sum game that some pundits like to describe. The emergence of Asia, Africa and Latin America can be to everybody’s benefit. The West stands to gain from increasing wealth in emerging economies because they will provide new markets for their products. For example, Germany’s auto industry has been steadily stepping up exports to Asia at a time when its traditional markets were looking gloomy.

By 2030, we will be in a different stage of our lives. The authors of this article will be close to retirement (and some of its readers as well). A new generation will be in charge and a new world will come about in making sure Kenya becomes one of the emerging economies of the 2030s.

------------------------------

Follow Wolfgang Fengler on Twitter @wolfgangfengler

Join the Conversation