Jobs are central to our lives: after all, we spend most of our time at work, trying to make a living. And it’s not just about what we earn. As the 2013 World Development Report argues, our work fundamentally defines who we are as people with important implications for our social relations and psychological well-being.

Each year, there are one million new Kenyans. Unlike in the past, this rapid population growth is driven by people living longer instead of having more children. This means that an increasing share of the population is of working age. What does it mean for Kenya’s economy and social stability? How can these young adults find a job—ideally a good job—and what needs to be done to help them succeed?

Young people are job seekers but also jobs creators. This is precisely why the ongoing demographic transition is both a challenge and an opportunity. Job prospects will improve in Kenya as young adults increasingly move out of family farming, to seek better prospects in cities. At the same time, out of the 800,000 Kenyans who reach working age each year, only about 50,000 are likely to find a “modern wage job”, securing a stable source of income. Others will evolve professionally in a grey area between traditional family farming and modern blue or white color jobs.

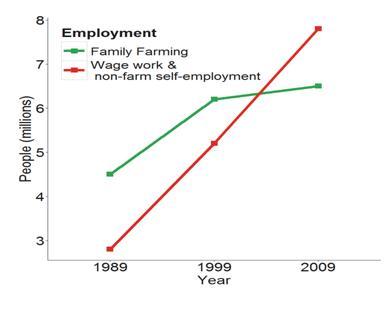

Twenty years ago, two-thirds of working Kenyans were on family farms (see figure). Today, that share has dropped to less than half, and it will fall further. The challenge is to create more opportunities for these youths to move to good wage jobs, and productive self-employment.

Figure – Kenyans are moving out of family farming

Young Kenyans face formidable hardships in finding work. Sadly, merit, skills and talent are not the main factors. With so many job seekers competing for scarce opportunities, employment often goes to those with connections, the “right” tribal affiliations or the ability to pay kitu kidogo. Women are particularly vulnerable to sexual abuse and harassment. Here is a first-hand account from an unemployed woman in Nairobi, from interviews we conducted with young Kenyans: “When people say that it’s God [who provides jobs] I don’t think it is God, your name must be there. Somebody needs to take your papers before you go for the interview.”

Kenya’s new Constitution outlaws discrimination and promotes equal opportunity for all Kenyans. This first legislative step is fundamental, but insufficient. As long as jobs are few, nepotism, favoritism and abuse will remain rife on the job market. What, then, can Kenya do to generate more and better jobs? Ninety percent of new jobs come from the private sector. So boosting job creation is chiefly about removing the obstacles that prevent dynamic Kenyan companies from flourishing. One key bottleneck is poor infrastructure. In Kenya, transport costs are prohibitive and power unreliable, putting the country at a clear disadvantage compared to competitors like China, India, and South Africa. The good news is that Kenya is on the right track: with new roads and power plants in the pipeline, these constraints are being addressed.

Another major impediment is corruption. On average, Kenyan firms devote 4 percent of their sales income on bribes. With what they pay on bribes, they could hire a quarter of a million people—roughly the number of young unemployed Kenyans in urban areas. This is just the tip of the iceberg. In fact the losses are much greater, because many companies do not come to Kenya in the first place, for fear of corruption. For example, British and American companies could face prosecution in their home countries if they were found to be paying bribes in Kenya. On the labor supply side, Kenyans will need to quickly and significantly ratchet up their skills. This means building on Kenya’s progress with Free Primary Education, improving school quality, and ensuring that more Kenyans finish secondary school. It also implies better aligning the education system with the job market.

In the foreseeable future, many Kenyans will continue to work in jua kali and other kinds of informal self-employment. To help these hard-working Kenyans prosper, local authorities and the new county governments should accept them as legitimate parts of the economy, rather than subjecting them to the harassment they often suffer.

These are some of the suggestions that came out of a recent World Bank analysis on jobs in Kenya. Now we want to hear from you! Participate in our poll and let us know your answer to the question “What is the biggest barrier to good jobs in Kenya?” Those in Kenya can participate in our poll by sending their answers via SMS to 0700 186 473. You can also participate by Twitter, using the hashtag #kenyakazini.

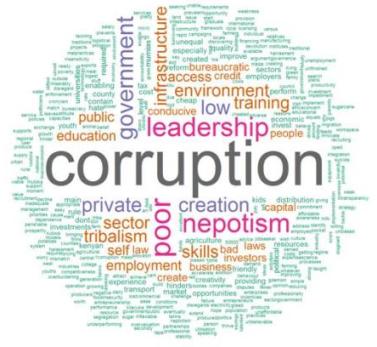

Below is a word cloud of the poll responses we’ve received to date. The most common barriers cited by participants were corruption, poor leadership and nepotism. Weak infrastructure (and the business environment more broadly), insufficient access to affordable credit, and the need to improve educational quality were also salient concerns. You can see a fee of the latest responses on the #kenyakazini Twitter page. For more detail on our analysis of jobs in Kenya, see the recent edition of the Kenya Economic Update.

Paul Gubbins contributed to this blog post.

Follow Wolfgang on Twitter @wolfgangfengler and Gabriel @gdemom

Join the Conversation