There has been an increase in attention on Africa’s changing population. Academics, development organizations and the media (among others, BBC, The Guardian, Financial Times, The Economist) have highlighted Africa’s late demographic transition – the population is young and will remain so for a long time, as fertility rates are not falling there at the same rate as they have fallen in the rest of the world.

Many are now advocating for smaller families in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) by appealing to economic pragmatism: fewer children per worker can lead to an increase in output per capita - a demographic dividend.

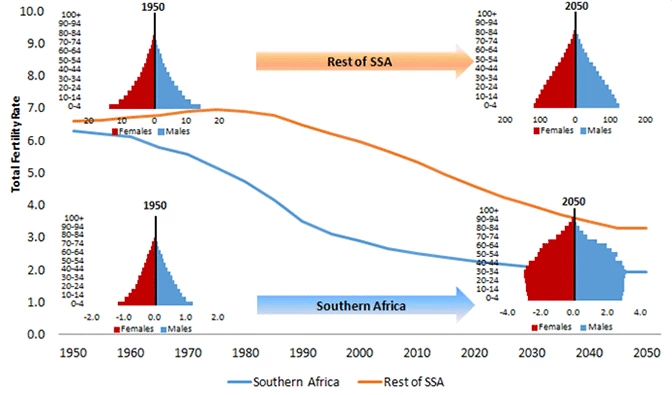

In a recent study we focus on a few African countries that are already at an advanced stage in the demographic transition, namely in Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, and Swaziland. In these countries, fertility started decreasing much earlier and faster than in the rest of the continent (Figure 1). As a result, Southern Africa is primed to enter a window of demographic opportunity.

Countries in Southern Africa provide a snapshot of how the population will look like for the rest of Africa in a few decades if fertility rates decline in a quick and sustained manner. As its recent experience shows, however, decreasing fertility is not enough to reap a demographic dividend. Creating good jobs and preparing youth for the labor market through sound social policies are equally important.

Figure 1: Differently from the rest of SSA, Southern Africa is already advanced in the demographic transition

Working-age, but not working

In Southern Africa, between 34 percent (Botswana) and 52 percent (Lesotho) of the working-age population is out of the labor force – they are neither working, nor looking for a job. Unemployment ranges between 17 percent in Botswana and 26 percent in Swaziland.

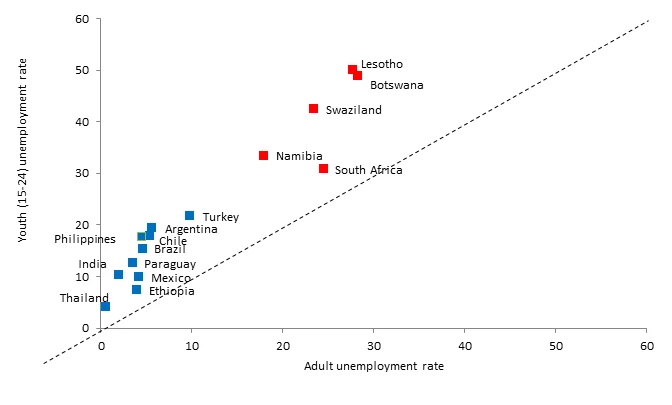

Matters are even worse among younger workers. The level of youth unemployment in Southern Africa is much higher than those of economically comparable countries and, with the exception of South Africa, the ratio of youth to adult unemployment is also higher (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Youth Unemployment Is More Severe than in Most Emerging Countries

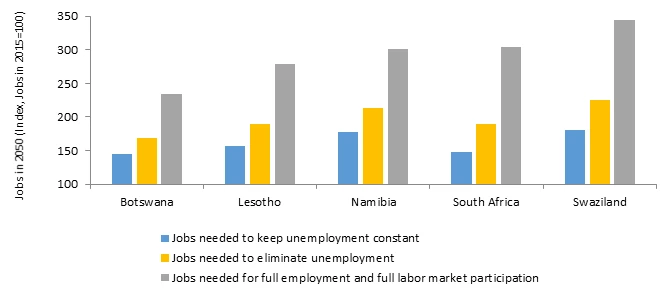

With the demographic transition comes millions of young workers looking for work. Just to keep (already low) employment rates constant until 2050, Southern Africa will need to create more than 7.6 million new jobs. And if countries were to employ the whole working-age population (including people who are now out of the labor market), the magnitude of the challenge would climb significantly further (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Harnessing the Demographic Dividend Requires Increasing Both Participation and Employment

The demographic transition is a slow process –generating good jobs, and providing youth with skills that are sought after in the labor market also takes decades. Inaction, however, would turn a potential demographic dividend into a demographic bomb with large cohorts of unemployed youth resulting to a tragic loss of human and economic potential.

Policies matter

It’s not too late for countries in Southern Africa to implement inclusive growth and social policies. Investing in these policies can benefit and boost gains for its current and upcoming large cohorts of working-age population (Figure 4). Improved educational attainment, for example, would allow the 2050 GDP per capita in Lesotho and Swaziland to be as much as 18 percent higher than under the current demographic and economic trends. And if South Africa were to converge to the current OECD male employment ratio by 2050, GDP per capita would quadruple.

Figure 4: Inclusive Growth Policies would Boost Gains from the Demographic Transition

Inclusive policies, unfortunately, do not always come cheap. They require substantial initial investments from countries that are often financially stretched.

Still, the Southern Africa experience may bring some positive news. Eventually, when fertility drops, the number of dependents shrinks, opening up fiscal space. Aggregate spending on education is forecasted to decrease between now and 2050 by two to three percentage points of GDP in all countries, thanks to the decrease in school-age population. And because the population is aging slowly, the demographic transition will take a substantial burden off health expenditures and social pensions in the next decades.

Countries in Southern Africa is at a cusp of reaping a demographic dividend. Investing in youth is key.

This blog is part of a blog series highlighting Southern Africa’s demographic transition.

Join the Conversation