Inflation remains nestled within the target range of 3-6 percent and fiscal and debt management outcomes have been impressive.

Remarkably, there is broad political consensus on the issue of macroeconomic stability, recent calls for a looser stance by the labor unions notwithstanding.

A sustained pattern of high, broad-based and inclusive growth is yet to emerge, however. Despite a pick-up in per capita GDP growth from negative rates to an average of 1.6 percent per year during 1994-2011, per capita GDP is currently only 10 percent higher than in 1980: a period over which other developing countries have seen much more meaningful increases in their income levels.

Growth has been insufficient, and insufficiently inclusive to absorb the massive wave of new entrants into the labor market since the mid-1990s, resulting in unemployment rates persistently above 20 percent.

Over 1980-2010, the average South African’s real income increased less than 10 percent, while the average Chinese became 13 times richer (PPP constant price GDP in US$, 1980 normalized to 100)

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

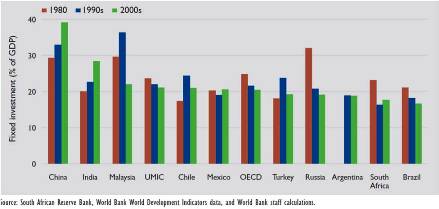

Among the main factors holding back a growth take-off are the country’s relatively low fixed investment rates. Currently at just under 20 percent, they are well below that of comparator countries, having dropped considerably since the last 1980s. This is explained by South Africa’s even lower national savings rates that, too, have also been on a declining trend (reasons for which may be found in the July 2011 South Africa Economic Update) as well as the tepid interest shown by foreign long-term investors. FDI as a share of GDP averaged only around 1.5 percent in the 2000s, being especially low in greenfield areas.

South Africa’s domestic fixed investment rate has slipped compared to other emerging market economies (click on the image to see it larger)

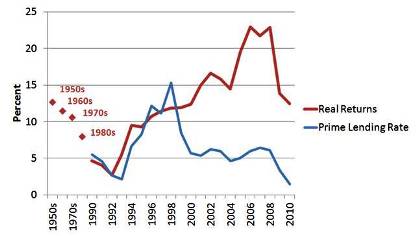

Why is the private sector hesitant to invest in South Africa’s future? Could it be that the returns on offer are not attractive enough? On the contrary, calculations of real returns to capital clearly show that South Africa is an attractive place to invest in (see the July 2011 South Africa Economic Update for details and sectoral breakdown of the returns). Real returns are high, have been sharply rising since the mid-1990s, and appear to be globally competitive. Moreover, the cost of borrowing (proxied by the real prime lending rate) has fallen sharply since the late 1990s. Clearly, something other than returns on investment is impeding private investment.

Real rates of return to capital in South Africa have risen sharply since the early 1990s.

Source: South African Reserve Bank data and World Bank staff calculations

An important impeding factor appears to be industrial competition, which is far weaker in South Africa than its international peers (as established by Aghion et al, 2008).

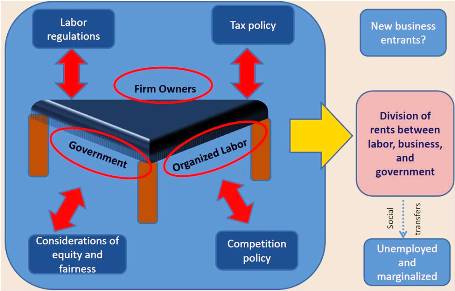

The three major (and most vocal) players in the political economy of reforms in South Africa – the government, organized labor, and existing business – appear not to be overly concerned. The status quo of industrial concentration and the associated exceptional returns works well from their point of view.

The triumvirate is locked in a continual, rambunctious public tussle over the distribution of the high rents being generated under the system. This tight-knit process does not call for entry of new businesses to normalize returns, and the noise it generates unintentionally drowns out the voices of masses that are unemployed and would like to see these exceptional returns translate into much higher investment, growth and job creation. The result is a suboptimal equilibrium that is hard to shift but may be at the heart of unlocking the much-desired path of higher, inclusive growth in South Africa.

A suboptimal political economy equilibrium (click on it to see it larger)

Join the Conversation