A clear pattern of 'two speed recovery' emerged from the global economic crisis: although the East Asian economies saw a drop of nearly 4 percentage points in their GDP growth to 8.5 percent in 2008 and a further decline to 7.5 percent in 2009, they rebounded quickly to 9.7 percent in 2010. At the same time, however, growth in high income countries fell by 6.6 percentage points during 2008-09, from 2.7 percent in 2007 to -3.9 in 2009. Moreover, these economies are not yet out of the woods given the sovereign debt crises in the Euro Area. This is one of the many fascinating patterns revealed in the newly updated online version of the World Development Indicators.

What is more striking is that low income countries (LICs) have been resilient during the crises, more so than in the past. The annual GDP growth rate for low income countries declined less than 1 percentage point in 2008, standing at 4.7 percent in 2009 and quickly recovered to 5.9 percent in 2010. In particular, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zambia have shown robust growth of 6 to 11 percent throughout this period. Similar conclusions were presented in Didier, Hevia and Schmukler April 2011.

GDP growth, East Asia, High-income, and Low-income countries

Data from World Bank

GDP growth, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zambia

Data from World Bank

One of the reasons appears to be that these low income countries have benefitted from strong spillovers from emerging market and other developing economies, particularly BRIC countries. Some would argue that LICs have been less affected by the global financial crisis because they are less integrated with the world economy. However, it should be noted that this lower degree of integration did not prevent low income countries from suffering sharp declines in economic activity in the past. Of course, improvements in macroeconomic management in recent years and strong international support helped mitigate the impact of the crisis, but it seems there is little doubt that low income countries' ever-increasing linkages with BRICs provided significant support to their growth during the crisis.

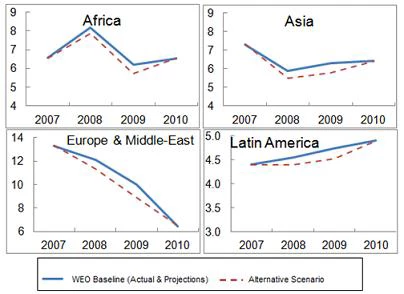

A recent IMF working paper by Samake and Yang provided empirical evidence on the spillover effects from BRICs to LICs. The authors estimated that the resilience of the BRIC economies during the financial crisis may have added 0.3 to 1.1 percentage points to LIC growth, as compared with a scenario in which BRIC GDP had declined at the same pace as advanced economies (See figure 1). This study employs several techniques to investigate the extent of business cycle transmission from BRICs to LICs through both direct and indirect channels. A global vector autoregression (GVAR) model is estimated to quantify the direct impact on LIC growth cycles of bilateral trade, FDI, productivity, and exchange rates, while a structural VAR model is used to estimate the effects of demand and technological change in BRIC economies on global commodity prices, demand, and interest rates, which in turn affect growth in LICs.

Figure 1 Real GDP Growth in Low Income Countries, Actual and Alternative Scenario

Sources: Samake and Yang, IMF Working Paper 11/267, 2011. Note: Blue line indicate actual & projection for 2010. The alternative scenario assumes that BRIC's growth declines at the same rate as that of Advanced Economies (2.5 percent in 2008, and 3.5 percent in 2009).

The estimation results show that there are significant direct spillovers from BRIC economies to LICs. The most important direct channel of transmission is trade, although productivity improvements in BRICs, and FDI flows from BRICs to LICs also matter. Trade accounts for around 60 percent of the impact on growth in LICs and is the most significant and persistent channel of transmission of shocks for all regions. The response in African LICs is particularly strong, reflecting the growing trade ties that these countries have forged with BRIC economies in recent years. The direct impact of productivity changes in BRICs, in turn, represents around 13 percent of the total impact. Asian LICs seems to subject to the strongest impact of BRIC productivity change, probably reflecting the closer integration of Asian LICs into global manufacturing supply chains, in which BRICs (particularly India and China) play a critical role. The FDI channel also matters but, compared with other spillover channels, its impact on LIC growth is more modest.

Spillovers from BRIC economies to LICs through global demand and price channels- namely indirect spillovers- are also significant, though generally smaller than the direct spillovers. BRIC's demand and productivity growth exert considerable influence over changes in some global variables. Spillovers through world commodity prices are the largest in the short run-roughly one third of changes in world oil prices can be attributed to shocks originating in BRIC economies. The indirect impact of BRIC demand and productivity through the global markets accounts for around 30 percent of the total impact of BRICs on LIC growth.

The overall (direct and indirect) impact of BRICs on LIC growth appears to be both substantial and growing. A one percentage point increase in BRIC's demand and productivity leads to 0.7 percentage point increase in LICs' output over 3 years and 1.2 percentage points over 5 years. These magnitudes are broadly similar to the direct impact of demand and productivity increases in advanced economies. The impact has increased from the pre-2007 period.

These results have significant policy implications. They point to the potential that increasing linkages with BRIC economies could change the volatility of LIC growth in the short run and contribute to their sustainable growth rates in the long run. Particularly, increasing LIC-BRIC trade and financial ties will only strengthen their business cycle synchronization over time. As long as BRIC business cycles are not fully synchronized with those of advanced countries, these growing ties should help dampen growth volatility in LICs.

As I have argued in my WIDER lecture that in an increasingly globalized world, opportunities for economic transformation abound - the coming graduation of China and other middle-income growth poles from low-skilled manufacturing sectors provides ample opportunities for low income countries to engage in labor intensive sectors and create millions of jobs. A recent IMF report reached the same conclusion that "Given China's large share in the world market for labor intensive manufactures, its upgrading to higher value- added products should leave sufficient room for low income countries and other latecomers, including India."

The emergence of a multipolar-growth world is clearly a blessing for the low income economies because it provides them the opportunities to reduce volatility and to enter a new age of industrialization and structural transformation. The more open these low income economies are to trade and investment and technology transfers, the bigger are the spillover effect.

The author wishes to thank Issouf Samake, Yan Wang and Yongzheng Yang for their contributions to this blog. The IMF Working Paper cited is part of a larger report by an IMF team, entitled “New Growth Drivers for Low-Income Countries: The Role of BRICs” prepared by the Strategy, Policy and Review Department in collaboration with the African Department, 2011.

Join the Conversation