Farmer African girl walking in farm field in Chad N'Djamena travel, located in Sahel desert and Sahara. Hot weather in desert climate on the Chari river in Africa.

Farmer African girl walking in farm field in Chad N'Djamena travel, located in Sahel desert and Sahara. Hot weather in desert climate on the Chari river in Africa.

It is commonly thought that a shock affecting agricultural production will translate into food insecurity a few months later––during the next lean season. However, high-frequency data from the Sahel shows that food security can drop much earlier, raising questions on how best to strengthen households’ capacities to absorb shocks.

Shocks and stressors, such as extreme weather events, economic downturns, and the COVID-19 pandemic, have adversely impacted people’s well-being across the Sahel, where households are among the poorest in the world. As a region constantly battered by shocks, there is substantial policy interest in strengthening people’s resilience––their capacity to absorb shocks, adapt to changing environments, and improve food security and well-being over time. Targeted interventions implemented at the right time can strengthen resilience: cash transfers can promote resilience to droughts, and cash transfers with complementary productive interventions can facilitate livelihood diversification.

The World Food Programme’s (WFP) integrated program in the Sahel aims to improve resilience through interventions that focus on strengthening resilience capacities. The program combines Food Assistance for Assets activities that address immediate food needs through cash, voucher, or food transfers, while simultaneously promoting the building or rehabilitation of assets that aim to improve long-term food security, with school feeding, nutrition, and Smallholder Agriculture Market Support interventions.

The WFP Office of Evaluation and the World Bank’s Development Impact Evaluation (DIME) department are working on the Climate and Resilience Impact Evaluation Window, which seeks to understand how WFP’s programming helps families build resilience to shocks. In Mali and Niger, with collaboration from the World Food Programme’s Country Offices and Regional Bureau in Dakar, impact evaluations will assess how WFP’s integrated resilience program strengthens resilience. These impact evaluations are part of a broader effort to strengthen the evidence agenda for resilience in the Sahel, funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). This blog coincides with the publication of the baseline report results for Mali and Niger.

Households are interviewed via in-person surveys before the program's start, every other month during program participation, and after the end of the program. Frequently surveying households allows us to capture both the immediate and the medium-term effects of shocks and assess how programming supports households as they recover. Before the program began, 4,841 households in Mali (January–March 2021) and 4,741 households in Niger (December 2020–January 2021) were surveyed. Since then, approximately 1,600 households were surveyed every other month in each country.

Sample households (in villages not participating in WFP’s integrated resilience program) are highly exposed to shocks, including floods and droughts/irregular rain. For instance, at baseline, between 33 and 38 percent of households in Mali and Niger experienced a flood, and between 27 and 38 experienced a drought during the year before the survey. However, exposure to shocks highly varies by season and depends on climatic shocks.

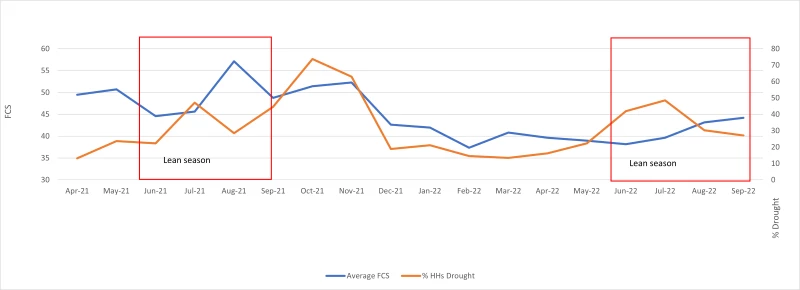

Most households in Mali and Niger are engaged in subsistence agriculture, and it is commonly thought that a rainfall shock affecting agricultural production will translate into food insecurity a few months later––during the lean season. However, the high-frequency data shows that food security (measured through the food consumption score or FCS) dropped immediately after the shock.

In October 2021, 74 percent of sample households in Niger reported a drought shock (orange line), where rainfall suddenly stopped before harvest. By December 2021, the average food consumption score had already dramatically decreased almost ten points (blue line). This shows that households quickly adjusted their food consumption in response to shocks and did so well before the next lean season. This suggests it is important to have programs that assist households in absorbing shocks before they hit and to build their resilience for future lean seasons.

Figure 1: Rapid Decline in Food Consumption Score Following Drought in Niger in October 2021

Assisting people at the right time ensures households don’t rely on negative coping strategies. As this impact evaluation work continues, we will assess how the WFP resilience programs help households absorb and adapt to shocks, including diminishing both the number of food insecurity spells and the use of adverse coping strategies. You can also find broader information about WFP’s impact evaluation work here.

The blog benefited from inputs from colleagues in the Climate & Resilience Window

Join the Conversation