We know that fiscal policy can be harnessed to reduce inequality in low- and middle-income countries, but until now, we knew less about its ability to reduce poverty. Our recent volume looks at the revenue and spending of governments across eight low and middle income countries (Armenia, Ethiopia, Georgia, Indonesia, Jordan, Russia, South Africa and Sri Lanka), and it reveals that fiscal systems, while nearly always reducing inequality, can often worsen poverty.

This volume can be viewed as a companion piece to the Public Finance Review issue The Redistributive Impact of Taxes and Social Spending in Latin America and to Commitment to Equity Handbook. Estimating the Impact of Fiscal Policy on Inequality and Poverty . Combined, the three publications present results for 30 countries, also featured in the CEQ Data Center on Fiscal Redistribution.

If policymakers are committed to ending poverty and improving the lives of their poorest citizens, they need to explore ways to redesign taxation and transfers so that the poor—especially the extremely poor—do not end up paying more than their fair share without reaping the benefits.

In our recent volume, we analyze the impact of fiscal policy on income inequality, by separating the “cash” portion of the system (direct taxes, direct transfers, indirect taxes, and indirect subsidies) from the “in-kind” portion (the monetized value of the use of government education and health services).

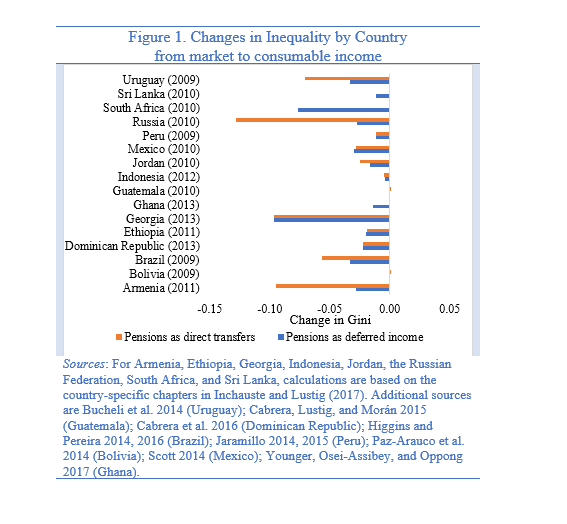

The results show that the reduction in inequality induced by the cash portion of the fiscal system is quite varied (Figure 1). Success is determined primarily by the amount of resources and their combined progressivity. We were not surprised to find that net direct taxes were always equalizing, but we were surprised to see that indirect taxes and subsidies also had an equalizing effect in six of the sixteen low and middle-income countries where a comparable methodology is available. When the analysis is expanded to the whole sample of 30 countries, this result is observed in 20 of the 30 completed countries.

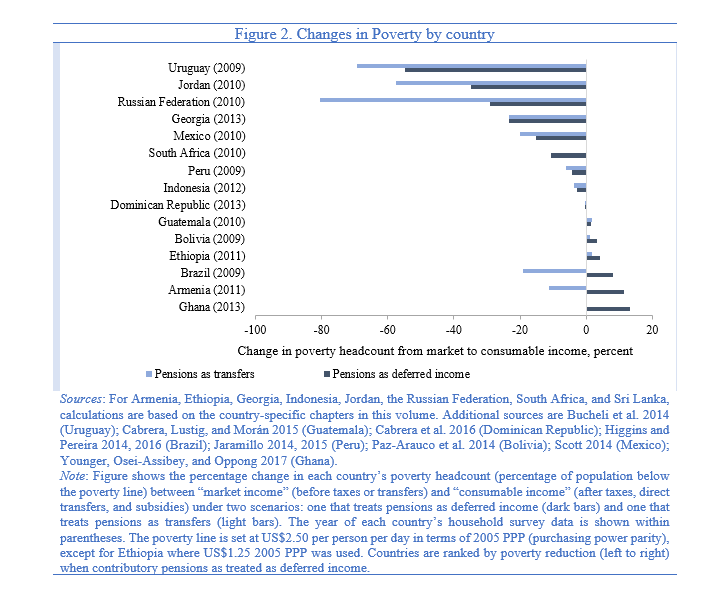

While the cash portion of the net fiscal system had a positive impact on reducing inequality, the same cannot be said for poverty. The results indicate that the poor in Armenia and Ethiopia, and the moderate poor in Sri Lanka are net payers into the fiscal system. This is because of high consumption taxes on basic goods in these countries (Figure 2). When we include the whole sample of 30 countries, the results indicate that the poor in Armenia, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Tanzania, and Uganda, and the moderate poor in Bolivia, El Salvador, Dominican Republic, Honduras, Peru, and Sri Lanka are net payers into the fiscal system.

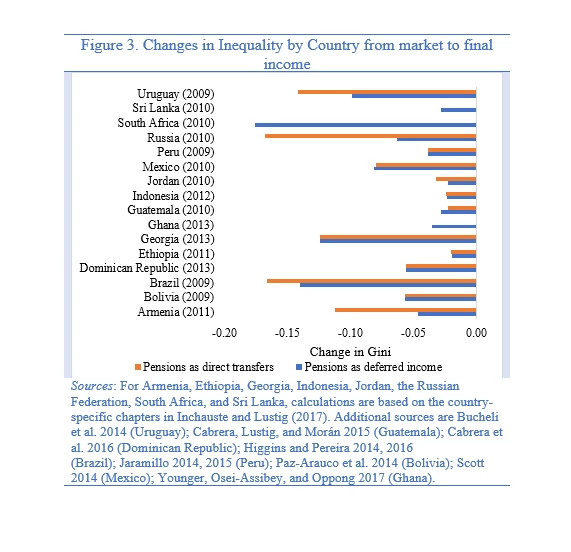

For the in-kind portion of the fiscal system, the set of case studies shows us that spending on education and health was equalizing and contributed largely to reducing inequality (Figure 3). This result is not surprising given that the use of government services is monetized at a value equal to average government cost.

While these results are encouraging for those who care about equity, it is important to note that they may be due to factors one would prefer to avoid. The higher use of government education and health facilities by the poor may be caused by the fact that the middle-class (and, of course, the rich) chose to use private providers, which often provide higher-quality services. This situation leaves the poor with access to what may be second-rate services. In addition, if middle-class people opt out of public services, they may be much more reluctant to pay the taxes needed to improve both the coverage and quality of services than they would be if services were used universally.

There are a few key lessons that emerge from our analysis. First, the fact that specific fiscal interventions can cancel each other out underscores the importance of taking a coordinated view of both taxation and spending rather than pursuing a piecemeal analysis. Efficient regressive taxes (such as the value-added tax) when combined with generous well-targeted transfers can result in a net fiscal system that is equalizing.

Second, to assess the impact of the fiscal system on people’s standard of living, it is crucial to measure the effect of taxation and spending not only on inequality but also on poverty. For instance, efficiently-designed regressive taxes can increase poverty even if combined with progressive transfers if the transfers aren’t large enough to compensate the poor.

Finally, policymakers can learn one fundamental lesson from our volume: governments should design their tax and transfer systems so that the incomes (or consumption) of the poor after taxes and transfers are not lower than their incomes (or consumption) before fiscal interventions. In short, fiscal policy should help improve the welfare of the least well-off, rather than pushing them into poverty or deepening their deprivation.

Join the Conversation