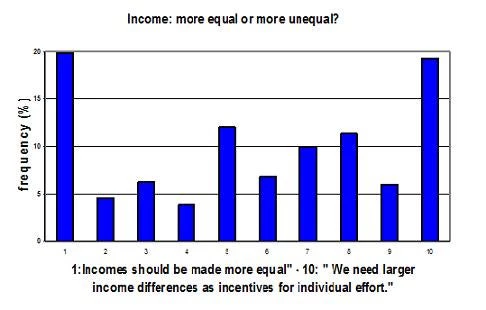

More than ten years ago Ronald Inglehart, of the University of Michigan, and his team at the World Values Survey asked thousands of respondents around the world to rate their views, on a scale of 1 to 10, on whether they felt inequality in their countries should go up or down. The way they phrased the question was that 1 corresponded to full agreement with the statement that “incomes should be made more equal”, whereas 10 stood for “we need larger income differences as incentives for individual effort”. The pooled results, across 69 countries, are given in the Figure below.

Not many questions in the World Values Survey (or any other) yield such an extreme bimodal distribution: the two most common responses were at polar ends of the spectrum, with about a fifth of the population each strongly supporting either more equality or more inequality! And although there was some inter-country variation, the same basic bimodal pattern actually held within most countries. The reason, I wager, is that income inequality is a composite of many sources. Some of it arises from differences in individual effort or responsibility – and many people find that those inequalities are justified, and in fact that more of them might provide the right sort of incentives.

But income inequality also reflects differences in basic life chances. In most countries in the world, the children of the rich and highly educated are much more likely to be rich themselves than the children of the poor, or of those with little formal education. These kinds of inequality, associated with circumstances beyond people’s individual control, are often thought of as much more objectionable. And, quite aside from any ethical objections, this ‘bad kind’ of inequality may also be detrimental to growth and efficiency if people with lots of potential are denied the basic opportunities to contribute to the prosperity of their economies and societies, some privileged people might benefit, but the overall pie is smaller.

These different kinds of inequality – inequality of incomes, educational inequality and inequality of opportunities – are the subject of the World Bank’s second conference on equity, which takes place at the Bank’s Washington headquarters today and tomorrow. Some of the pioneers in thinking about inequality of opportunity in economic terms, like John Roemer and Dirk van de Gaer, will be in attendance, alongside other big names in the poverty and inequality field, like James Foster.

The topic of the conference - “Inequality of What? Outcomes, Opportunities and Fairness”– harks back to Amartya Sen’s famous question at his Tanner Lectures, more than three decades ago. And you may think such a conference was to be expected, at a time when inequality is high on the agenda, both in countries where it has been rising relentlessly, like China and the US, and in those where it has fallen markedly, like Brazil, Peru and Mexico. And in an institution which, since the WDR 2006, has devoted much paper and cyberspace to inequality of opportunity, and the Human Opportunity Index.

My own hope, however, is that this conference will dig deeper into these issues and help to steer the debate forward. Here are some of the questions I would like to see answered or, at least, addressed:

• What are the differences between the Human Opportunity Index and other measures of inequality of opportunity, such as those more commonly used in the academic literature? Are they complements or substitutes? Why?

• Amartya Sen’s own answer to his question about what inequality really mattered had to do with functionings and capabilities. These concepts are inherently multidimensional, whereas much of the work following Roemer and/or van de Gaer focuses on a single dimension of ‘advantage’. Does that matter?

• In places like Egypt, where one often hears that “inequality” contributed to spurring the Arab Spring, both income inequality and inequality of opportunity – as currently measured – are relatively low. Are our measures of inequality of opportunity really credible? Do they miss some fundamental aspects of ‘process fairness’ that should be reflected?

• There is some evidence that income inequality and economic mobility are negatively correlated (as per Miles Corak’s “Great Gatsby Curve”). And that income inequality and inequality of opportunity are positively correlated, which makes sense, since inequality of opportunity and (the inverse of) mobility are closely related. If that is so, are all these distinctions splitting hairs? Should the Bank assist governments in reducing inequality of opportunity, inequality of incomes, or both? Or neither?

It should be an interesting couple of days.

Conf. LIVE STREAM LINKS

Opening, Keynote Address & Plenary: Windows Media | Flash

Parellel Session: Windows Media | Flash

Join the Conversation