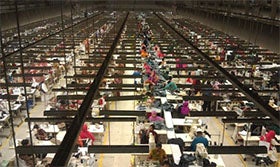

How have China and other countries resolved the binding constraints in light manufacturing to create jobs and prosperity? This vital question is answered in a new book based on unprecedented access and detailed interviews at hundreds of Chinese firms in more than 15 cities (including the coastal regions that have fuelled the export boom), as well as visits to a dozen countries in Africa and Asia. The book, Tales from the Development Frontier: How China and Other Countries Harness Light Manufacturing to Create Jobs and Prosperity, focuses on labor-intensive manufacturing (apparel, leather goods, agribusiness, woodworking, and metal products). It is part of the Light Manufacturing in Africa Project being undertaken by a World Bank team in the Development Economics Vice Presidency. We draw from analytical reviews, case studies, and the testimony of individual entrepreneurs to show how developing countries can grow manufacturing to create jobs and foster prosperity.

How have China and other countries resolved the binding constraints in light manufacturing to create jobs and prosperity? This vital question is answered in a new book based on unprecedented access and detailed interviews at hundreds of Chinese firms in more than 15 cities (including the coastal regions that have fuelled the export boom), as well as visits to a dozen countries in Africa and Asia. The book, Tales from the Development Frontier: How China and Other Countries Harness Light Manufacturing to Create Jobs and Prosperity, focuses on labor-intensive manufacturing (apparel, leather goods, agribusiness, woodworking, and metal products). It is part of the Light Manufacturing in Africa Project being undertaken by a World Bank team in the Development Economics Vice Presidency. We draw from analytical reviews, case studies, and the testimony of individual entrepreneurs to show how developing countries can grow manufacturing to create jobs and foster prosperity.

How is it possible that the owner of the world’s largest producer of roller ball pens never finished elementary school and could not even write his name well? The tale about Zhang Hanping and the Aihao Writing Instruments Co. in our book shows how resiliency helps an uneducated person to keep on trying until he rises to the top. Similarly, how does a small village in Qiaotou, Zhejiang Province, produce roughly 60 percent of the world’s buttons and sell about 15 billion buttons a year? Who started the business? What helped transforming this dirt poor village into its present position? The black high-heeled shoes worn by the U.S. First Lady, Michelle Obama, at her husband’s 2009 inauguration became a popular item overnight: 500,000 pairs were sold within a short time. The shoes were produced by Roeblan, a footwear enterprise in Chengdu owned by Wu Deguo. How did Wu and Roeblan grow from a small family workshop to a modern company? The book tells these tales and many more.

Tales from the Development Frontier is divided into three parts. Part I focuses on China’s 20th century experience in developing light manufacturing, with particular emphasis on developments under the reforms and opening up policies which begun in the late 1970s. The book highlights the obstacles facing early entrepreneurial start-ups and explains how government initiatives and emerging public-private cooperation combined to help light manufacturing take off. The application of these tools is illustrated through numerous case studies of individual Chinese entrepreneurs, firms, and industries.

Part II uses case studies of firms and industries in other African and Asian developing countries to further illustrate the role of government policies in accelerating light manufacturing growth, but also the dangers of ignoring the binding constraints facing the respective industries.

Part III summarizes the policy lessons drawn from the book for the development of light manufacturing elsewhere. These lessons illuminate the prospects for rapid industrialization in developing countries through the creation of an environment for manufacturing, the narrowing of knowledge and financial gaps through foreign direct investment and networks, the use of substitution policies and the sequencing of reforms, starting small and building gradually, and establishing islands of success by keeping targeted policies selective and within a country’s limited resources.

The book offers vivid insights into how China has become the world’s second largest economy. While focusing on domestic competition and international openness as key drivers of growth, the study also highlights the contribution of underappreciated policy tools such as industrial parks, industrial clusters, and trading companies and emphasizes the centrality of cooperation between the public and private sectors in promoting the remarkable expansion of light manufacturing in China. Development started in China and can begin elsewhere through the emergence of small, private businesses that are able to grow even if overall economic conditions remain far from ideal. Once new clusters begin to emerge, the government can respond by supporting market-tested winners: an approach that is different from seeking to identify winners from the outset.

The current erosion of China’s cost advantage is producing substantial possibilities for the rest of the developing world. However, instead of adopting an economy-wide, first-best approach that attempts to tackle a wide array of development problems simultaneously across entire national economies, developing countries would be better off to implement sharply focused policy initiatives aimed at specific industries and locations to inject new elements of prosperity and growth without trying to roll back all the constraints affecting large segments of the economy. Development and industrialization begin somewhere, not everywhere. Without initial breakthroughs in specific sectors or locales, poor countries are unlikely to avoid a protracted stalemate between poverty and growth.

Of course, it is true that prospective entrants into the fiercely competitive world of light manufacturing now confront a higher standard than China, Japan, or the Republic of Korea faced in the past. But the steep decline in international transaction costs, the size and visibility of global markets for products such as garments, toys, and furniture that are within the technical grasp of low-income producers, and the greater availability of footloose capital, entrepreneurship, and market knowledge that can help poor nations create viable platforms to serve domestic and overseas markets represent a confluence of circumstances that can and should support a new round of tales of development success.

Join the Conversation