It’s quite fun being picked up by a prime minister. Not literally of course. Unless you happen to be a baby seized from your mother’s arms during an election campaign, in which case it must be rather exciting, and quite possibly the highlight of the day. No, I mean being picked up in print.

In a recent Washington Post op-ed, former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown, and current United Nations’ Special Envoy for Global Education, cited a Let’s Talk Development blog post of mine asking whether inequality should be reflected in the new international development goals. Toward the end of the post I presented some rather shocking numbers showing how – in a large number of developing countries – the poorest 40% have made slower progress toward key MDG health targets than the richest 60%. Although I didn’t actually offer any evidence on education, I argued: “If inequalities in education and health outcomes across the income distribution matter, and if we want to see “prosperity” in its broadest sense shared, it looks like we really do need an explicit goal that captures inequality.”

Brown cited the health data, and concurred with my conclusion, writing: “While the public justification for all our efforts is to offer the most help to the poorest and most vulnerable, setting a universal goal without targeting the most disadvantaged is a recipe for them to be left behind. And when the next set of Millennium Development Goals – with more ambitious universal targets for learning outputs and secondary education – raise the ceiling before we have put the floor in place, then they will continue to lose out.”

Since Brown’s op-ed, current UK Prime Minister, David Cameron – along with co-chairs of the High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, President of Indonesia, and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, President of Liberia – has thrown his weight behind the idea that without explicit targets for them, poor children will be left behind. In their recently-published report, Cameron and his fellow panelists wrote: “We propose targets that deliberately build in efforts to tackle inequality and which can only be met with a specific focus on the most excluded and vulnerable groups. For example, we believe that many targets should be monitored using data broken down by income quintiles and other groups. Targets will only be considered achieved if they are met for all relevant income and social groups.”

As I read all this, I felt I needed to some dotting of i’s and crossing of t’s. Yes, we know that poor children were left behind by the health MDGs. But were they actually also left behind by the education MDGs?

The basics

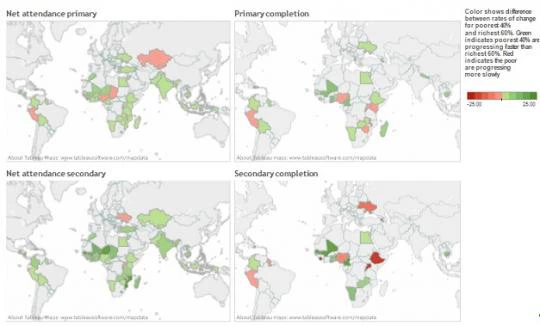

The task of completing the picture on the progress among the poor for the education and health MDGs isn’t an arduous one. My education colleagues in the World Bank have already produced the necessary data. They have computed quintile-specific data for key education indicators – attendance and completion of primary and secondary education, and years of schooling among young people aged 15-19 – for a large number of countries, often for several years. It’s just a few steps from these data to average annual rates of growth for the poorest 40% and richest 60% for each country, and maps of the results.

The first set of maps below show whether progress on primary and secondary attendance and completion has been slower (red) or faster (green) among the poorest 40% than the richest 60%. There’s quite a lot of green, which is encouraging and shouldn’t be forgotten. But there’s also quite a lot of red. So, yes, it is true that in education – as in health – poor children haven’t always made as fast progress as the better off toward the MDG goals.

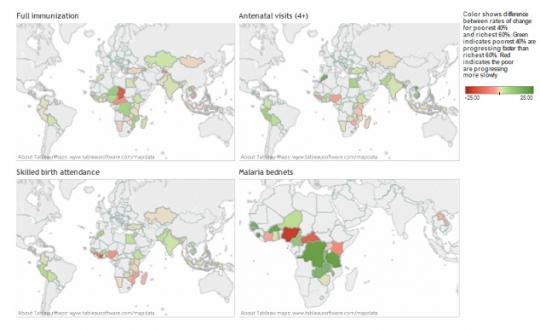

To allow some comparisons with health, the second set of maps show “excess growth” among the poorest 40% for four of the health MDG indicators. There’s actually slightly more red in these maps. So if Brown is right to raise the alarm for education, his health counterpart at the UN would be at least as right – if not more so – to raise the alarm for health.

More countries and a more demanding education indicator

Unfortunately far fewer countries have trend data on primary school completion (28) than on primary school enrollment (50). So there are lots of countries that have a pro-poor growth of primary school enrollment for which we don’t know whether their growth of primary completion is also pro-poor. The secondary attendance data help here, but only so far – a lot of children drop out of school after primary school. And in any case, as Brown argues, the primary completion target isn’t terribly ambitious.

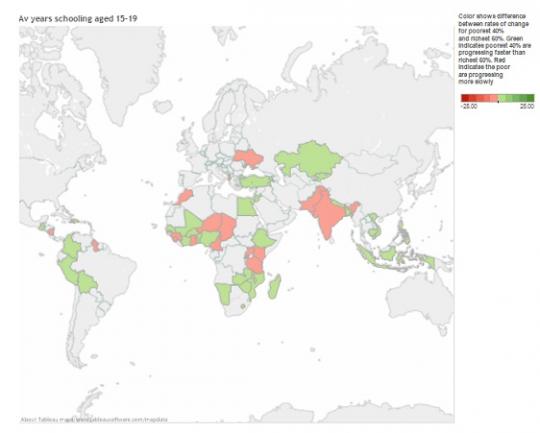

Years of schooling among young people aged 15-19 is an indicator that has been computed for 50 countries, and is a more demanding indicator than primary completion. The map below shows that is a sizeable fraction of countries (one third) the poorest 40% have seen slower progress in years of schooling than the richest 60%. That’s quite a sobering statistic.

Next stop UN General Assembly

The maps above suggest I wasn’t barking up the wrong tree in urging the devisors of the post-2015 targets to think about explicit human development targets for the poorest. So it’s good we have a couple of prime ministers and a large group of eminent persons now making that case.

All eyes are now on UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. At the end of September he is expected to present his vision for post-2015 development agenda at the UN General Assembly. The world’s poor will be watching closely.

Join the Conversation