How does Serbia fare on gender equality in the labor market? Did it manage to sustain some of the achievements of the former socialist regime, such as equal access to education opportunities, equal treatment of men and women in the labor law and high employment rates of men and women? The analysis of the recent labor force and enterprise surveys shows that although men and women have similar education levels and enjoy equal treatment in the labor legislation, there are major gender disparities in access to economic opportunities:

- The employment rate of working age women is 26% lower than men’s while the inactivity and unemployment rates are much higher.

- There is a significant wage gap between men and women in a number of sectors and occupational groups with low educated women being particularly disadvantaged.

- Women are markedly underrepresented in the business world, comprising less than 30% of the self-employed and company owners.

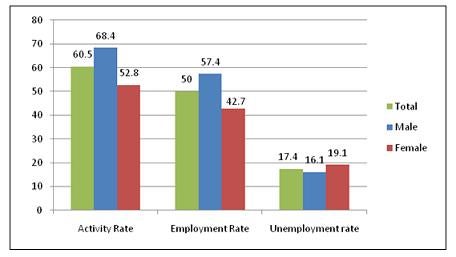

Although the overall labor market situation is difficult, women appear to be disproportionately affected with only 43 percent of working age women being employed (Figure 1). The reasons that hamper women’s employment and career advancement include 1) lack of childcare institutions, particularly in rural areas, which limits women’s labor market participation; 2) lack of flexible work arrangements; 3) relatively long average working hours (42 for women and 45 for men); 4) low market demand for female labor (particularly unskilled) and 5) stereotypes about traditional roles of men and women.

Figure 1. Labor market indicators for working age men and women in Serbia, 2009

Source: LFS 2009

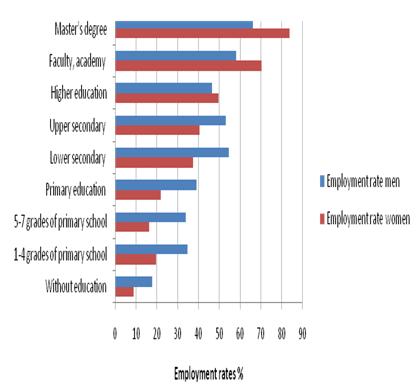

Education is a major determinant of employment outcomes (Figure 2). Only 22% of women with primary education versus 84% of those with a master’s degree have a job; the respective rates for men are 19% and 71%. Low activity and employment rates of less skilled women can potentially be explained by several factors. First, women with low educational attainment may be more likely to follow traditional social roles where a man is seen as the breadwinner and a woman’s role is limited to household’s responsibilities.

Figure 2. Employment Rates and Educational Attainment of Working Age Men and Women in Serbia, 2009

Source: Serbia LFS, 2009

When asked about reasons for not seeking a job, over one-fifth of low educated women versus one-tenth of women with tertiary education name household responsibilities as the reason for inactivity. Second, there may not be enough jobs offering attractive remuneration rates for low skilled women making it worthwhile for them to enter the labor force. Studies from other countries, e.g. the export-oriented flower industry in Ecuador show that when opportunities for women’s gainful employment arise, households reallocate family responsibilities, with men spending much more time doing housework allowing women to get advantage of paid employment. Third, salaries of low educated women are much lower than those of low educated men; with women who have completed only primary education (eight years) receiving 24% less than men with similar education levels, which may be a disincentive for women to enter the labor force.

Women are paid less than men in all occupation groups and in most sectors. The highest gender-based wage differentials are observed among skilled agricultural workers, where the average wage gap reaches 27%. However, the overall wage gap, controlled for individual worker characteristics, is rather small by regional and global standards - 5% in 2009 down from 9% a year earlier. The decrease in wage differentials was likely due to the financial crisis that had a greater impact on male-dominated sectors such as construction. Regression analysis has shown that employed women on average have better characteristics (e.g. better education levels) than men but receive lower returns on these characteristics. In fact, if employed men possessed the same qualities as employed women, the wage gap would have been larger. The analysis has also demonstrated that the wage gap is indicative of discrimination against women in the labor market as earnings differentials cannot be explained by differences in observed characteristics of male and female workers.

Serbian women also face constraints in starting and developing their businesses and may be subject to a greater regulatory burden than their male counterparts. Female-owned businesses are more likely to consider customs and trade regulations, tax administration, licensing and permits as a major or severe obstacle to firm operation. They are also almost twice as likely to report providing additional payments or gifts to get things done when dealing with government officials (Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey, 2009).

These findings suggest that Serbia has a significant and largely untapped economic potential represented by those women who either do not enter the labor force or who do not have the opportunities to start up and grow their businesses. Two facts make women’s greater participation in the labor force attractive for the economy: almost 70% of the population is in the working age group offering a potential for increased economic growth; and more than 60% of GDP comes from services, a sector that offers greater opportunities for female employment.

For more information, please see the paper “Gender Inequality in the Labor Market in Serbia.”

Join the Conversation