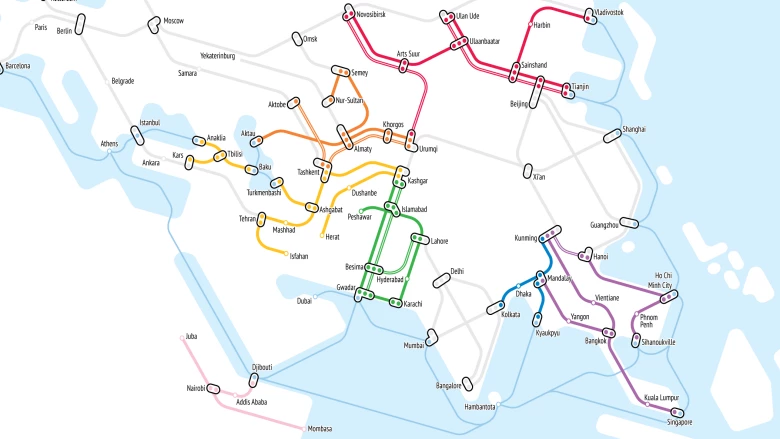

丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路的六条陆上走廊可以改善交通,并连接许多国家。

丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路的六条陆上走廊可以改善交通,并连接许多国家。

China’s signature foreign policy project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has seen many successes. Over 125 countries have signed up, and projects are being implemented across Asia, Europe, Africa and beyond. In April, the 2nd Belt and Road Forum reaffirmed the government’s commitment to the initiative, as well as its desire to address the unique challenges inherent in large, cross-border infrastructure.

But largely absent from the discussion so far is hard evidence of what the BRI can—and cannot—do to improve trade, increase incomes, and reduce poverty. Also missing is a careful assessment of the risks that these projects might entail. In the absence of empirical analysis, the initiative has attracted the greatest attention from its most ardent supporters and vociferous critics.

Quantifying impacts for the BRI is a major challenge, given the initiative’s size and scope and limited data available. When infrastructure crosses borders, the benefits from increased connectivity are magnified—but so are the risks. That is why the World Bank has spent the last two years studying BRI transport projects through empirical research, economic modeling, and rigorous evaluation.

Our aim has been to provide countries an independent analysis of the risks and opportunities of Belt and Road transport corridors. This will allow all participants, including China, to choose the kinds of investments and reforms that will best meet their development needs. The study also aims to inform the public debates surrounding BRI, by grounding the discussion in data and analysis.

The World Bank’s study concludes that the Belt and Road transport corridors could substantially improve trade, foreign investment, and living conditions for citizens in participating countries—but only if China and BRI participants adopt deeper policy reforms that increase transparency, expand trade, improve debt sustainability, and mitigate environmental, social, and corruption risks.

Countries along the BRI corridors are highly diverse. But they share one key characteristic: they require large investments to improve transport and logistics infrastructure. Moreover, many BRI corridor economies, particularly low-income countries, are poorly integrated into regional and world markets. In BRI corridor economies, trade is estimated to be 30 percent below potential, and FDI is 70 percent below potential.

BRI transport corridors will help in two critical ways: by lowering travel times and by increasing trade and integration. Along the corridors, transit times are expected to decline by up to 12 percent. This matters: one day less in transit would increase trade by 5.2 percent. Transit times are also estimated to decrease by an average of 3 percent with the rest of the world, showing that even countries that don’t participate in the BRI will benefit from roads, rails, and ports built in BRI corridor economies.

We estimate trade could grow from between 2.8 and 9.7 percent for BRI corridor economies, and between 1.7 and 6.2 percent for the world. Not all countries would see positive trade effects, but aggregate effects would be positive—because all countries would experience a decline in trade costs. Sectors that are time-sensitive (such as fresh fruits and vegetables) or require time-sensitive inputs (such as electronics and chemicals) will benefit the most. Low-income countries could see a 7.6 percent increase in foreign direct investment.

Increased trade is expected to increase global real income by 0.7 to 2.9 percent. The largest gains are expected for BRI corridor economies, with real income gains between 1.2 and 3.4 percent. BRI transport projects could help lift 7.6 million people out of extreme poverty (those earning less than $1.90 a day) and 32 million people from moderate poverty (those earning less than $3.20 a day). Most of the poverty reductions would be in BRI corridor economies.

But even though the total economic impacts would be positive, gains would be unevenly distributed. In Kyrgyz Republic, Pakistan, and Thailand, real income gains could be above 8 percent. But for Azerbaijan, Mongolia, and Tajikistan, the high costs of infrastructure could exceed the gains from greater connectivity and economic integration, in the absence of other reforms.

Complementary policy reforms are essential for countries to unlock BRI benefits. Participating countries will need to make it easier to import and export goods. Real incomes for BRI corridor economies could be two to four times larger if trade facilitation is improved and trade restrictions are reduced. In addition, countries will need to strengthen investment protection and improve the environment for private sector participation.

Policy reforms will also be necessary to mitigate the considerable risks associated with large infrastructure projects. About one-quarter of Belt and Road corridor economies already have high debt levels—and for a handful of these economies, our analysis shows that medium-term vulnerabilities could increase. Even for countries without high debt levels, the tradeoffs of a BRI investment must be considered carefully. Projects should be consistent with national development priorities. The value of individual transportation projects depends on realizing others. And where benefits of transport investments would accrue mostly to neighboring countries looking to transit, these neighbors could be asked to shoulder the risk, for instance through public private partnership.

Large infrastructure projects create governance risks, including corruption and failures in public procurement. The limited data available indicate that Chinese firms account for the majority of BRI contracts—according to one estimate, more than 60 percent of Chinese-funded BRI projects are allocated to Chinese companies. Little is known about the processes for selecting firms. Moving toward international good practices such as open and transparent public procurement would increase the odds that BRI projects are allocated to the firms best placed to implement them.

Environmental and social risks also must be considered. Many BRI routes pass through areas vulnerable to degradation, flooding, and landslides. BRI transport infrastructure is estimated to increase carbon dioxide emissions by 0.3 percent worldwide—but by 7 percent or more in Cambodia, Kyrgyz Republic, and Lao PDR as production expands in sectors with higher emissions.

Enacting the necessary reforms will not be easy. Reforms to open trade and reduce delays at the border will require dealing with vested interests. Managing fiscal risks will require improvements in data reporting and transparency, which depend on better coordination among government bodies, lending institutions, private sector firms, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China.

China is well-positioned to facilitate these reforms. It has vast experience building large-scale infrastructure projects. It has grappled with formidable obstacles in project financing, community engagement, and coordination issues. Today, it is sharing these experiences with other BRI participants. China also announced a series of initiatives at the BRI Forum in April to improve transparency, combat corruption, and address environmental concerns.

These are important steps. But bolder and deeper policy reforms will be required for the ambitions of the BRI to be realized and its risks mitigated. Three core principles must be upheld:

Transparency: Providing more public information on project planning, fiscal costs and budgeting, and procurement will improve the effectiveness of individual infrastructure investments and national development strategies.

Country-specific reforms: Making it easier to import and export goods is essential for countries to reap the benefits of BRI investments. In addition, countries should adopt open procurement processes, strengthen governance, and establish fiscal and debt-sustainability frameworks that allow them to fully account for the costs of debt-financed infrastructure.

Multilateral cooperation: Multilateral frameworks can help countries work together to improve trade facilitation and border management, unify standards in building infrastructure, agree on legal standards and investor protections, and manage environmental risks.

The BRI represents an enormous opportunity—particularly for countries that have long been at the periphery of the world economy. It should not be squandered.

Related links:

- Down the Report: Belt and Road Economics

- Press Release: Success of China’s Belt & Road Initiative Depends on Deep Policy Reforms, Study Finds

(Originally published on Caixin)

Join the Conversation