Vietnam has achieved remarkably high and inclusive GDP growth since the late 1980s. GDP growth per capita increased three-and-a-half-fold during 1991-2012, a performance surpassed only by China. The distribution of growth has been as remarkable as its pace: the bottom 40% of the population’s share in national income has remained virtually unchanged since the early 1990s, ensuring that the rapid income gains got translated into shared prosperity and significant poverty reduction.

GDP growth, however, has been operating on a lower trajectory since 2008. This has led to questions regarding the sustainability of the growth process, and, with it, Vietnam’s ability to bounce back to about 7-8% per capita growth. Analysts have voiced concerns over declining total factor productivity growth and growing reliance on capital accumulation. Moreover, a number of competitiveness issues routinely get raised by private investors, including: a widening skills gap, limited access to finance, relatively high trade and transport logistics costs, an overbearing presence of the SOEs, and heavy government bureaucracy that makes it difficult for businesses to operate in Vietnam.

One of Vietnam’s great advantages is its location – within the world’s most dynamic region. The rapid ascents of Japan, Korea, Malaysia, and China are steeped in the Vietnamese mindset. Therefore, success, to a large extent, gets defined as much in a relative sense as in an absolute sense. While the initial long spell of rapid growth was taken in stride, there is now a concern that Vietnam risks getting left behind by the regional superstars.

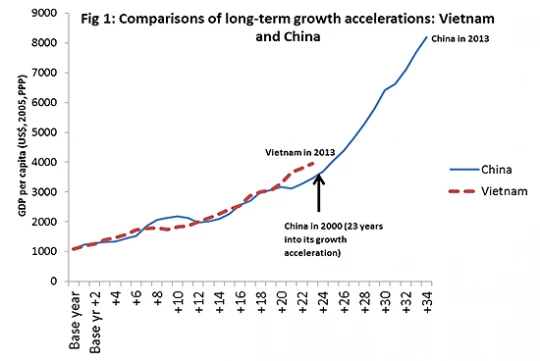

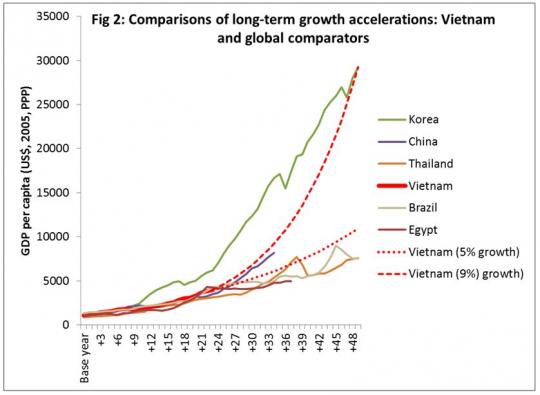

Has long-run growth in Vietnam run out of steam sooner than in its celebrated regional peers? To answer this, we would need to compare Vietnam today with where the peers were at this stage of their growth acceleration. Figure 1 makes that comparison with China, and is striking on two counts. First, growth accelerations in both China and Vietnam started at roughly the same per- capita income level. Second, by 2013 Vietnam had kept pace with China also 23 years into its growth acceleration. Figure 2 adds other successful countries to the comparison and considers a 50-year period. The story remains broadly similar. Vietnam’s current position is broadly at par with that of the other economies at a similar stage of growth acceleration.

Of even greater consequence than past comparisons is what happens from hereon. It seems that roughly 25 years into their respective growth accelerations – Vietnam’s current stage – was where the successful countries such as Korea, and China started to pull ahead of the rest. Vietnam, therefore, stands at a consequential juncture. If it can pull up its GDP growth to the peak rates of 9% or thereabouts, then it can realistically aim to become an industrialized nation within a generation – with income levels equaling those of Korea today. On the other hand, if it continues on recent-year growth rates of just over 5 percent, then that will take its average income to levels slightly above those of Thailand, Brazil or Egypt today.

In navigating future policy challenges, Vietnam will find useful lessons in the experiences of the successful countries in the region. For example, in the 1980s, South Korea significantly reduced government intervention and liberalized the import and foreign investment regimes to promote competition. Concerned over rural-urban imbalances, the government ramped up public investment in infrastructure, and promoted farm mechanization. In similar vein, China introduced a number of measures in the early 2000s that began to reform the banking sector and allowed the formal private sector to develop.

What kinds of policy choices is Vietnam faced with? The immediate impediments to private sector growth identified above will clearly need to be tackled. Resolution of the long-standing issues of SOE and banking sector restructuring will also remain important. To follow the example of its successful East Asian neighbors, Vietnam will also need to ensure greater value addition from exports and continual quality enhancements of its exported goods – areas where it has been lagging. Much like its successful East Asian peers; Vietnam’s main resource is its people. Investing in promoting a universally strong human capital base, therefore, is a prerequisite for Vietnam’s long-term growth. Finally, a powerful lesson from the successful countries is that a much stronger focus will be needed on improving urban management (building cities for the future) and on modernizing agriculture and making it more private sector oriented.

These issues, and policy options to address them, will be part of joint work between the Government of Vietnam and the World Bank on a study that will explore how the country can achieve its longer term aspirations to become a modern industrialized economy that is more resilient and inclusive.

Source: Penn World Tables 8.0. Note: Base years are 1990 for Vietnam, 1977 for China, 1962 for Korea, 1951 for Brazil, 1958 for Thailand, and 1969 for Egypt.

Join the Conversation