The notion that the generation and dissemination of information can be a tool to improve learning outcomes in developing countries has been around for a while. Barbara Bruns, Harry Patrinos and I recently published Making Schools Work, a book that reviews the evidence from recent impact evaluations of reforms that aim to promote accountability. We focus on three approaches to accountability that are increasingly being tried in developing countries—the generation and dissemination of information, the devolution of decision-making to the school level, and incentivizing teacher effort and performance.

There are several reasons why information dissemination might lead to better outcomes. First, it could increase the choice that people have about which is the right school for them. The subsequent “market pressure” can lead to more effort and better outcomes. Second, it can promote participation since information can shake up the belief that performance is adequate, spurring parents and others to action. Also, since information provides yardsticks, it can enable increased monitoring of performance. Third, it can increase the parents’ and students’ voice (by providing it with externally validated content) and empower them in their interactions with both school authorities as well as local political and administrative authorities.

So does it work in practice?

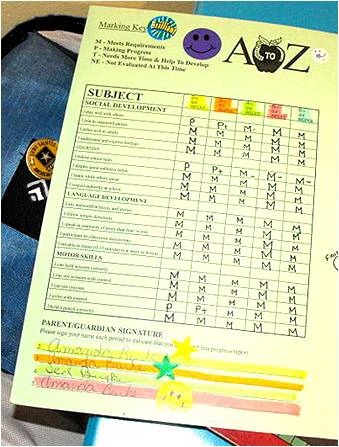

Information can improve outcomes. For example, one study in Pakistan showed that the provision of school report cards (comparing student, school and village scores) resulted in increased test scores in public and private schools, and reduced fees in private schools. Another study in three states of India showed that raising the awareness of the rights and responsibilities of village education oversight groups (such as Village Education Committees) increased several of the test scores measured as a part of the study. In Uganda researchers showed that a media campaign focused on disseminating the dates and amounts of school capitation grants led to lower leakage—and also to higher enrollments and test scores.

But information is not a panacea. In our book, we also point to another study in India which found no impacts on learning outcomes—or any other behaviors measured—of an awareness raising campaign. Disseminating the results of an Early Grade Reading Assessment in Liberia had no effect on learning outcomes—although when combined with training teachers in reading instruction impacts were large. In Chile, a study of the impact of the publication of league tables which rank schools found no effects on enrollments or any other school behaviors.

What made information effective in some settings but not others? Given the limited number of cases any conclusions have to be tentative at this stage. Two key features seem to be (1) keeping information simple, and (2) making sure that the intended recipients understand it. Also, being able to do something in response to the information is important. This can be either at the household level when it comes to school choice, or at the school level where schools and teachers need to know how to improve performance.

When the constraint on quality is relatively easily addressed—through squeezing out more instructional time as was the case in Pakistan, or reducing absenteeism as was the case in the Indian three-state study—this is relatively easily done. When constraints are harder to overcome—for example finding the most appropriate pedagogical approach to dealing with a heterogeneous classroom—it is unlikely that information on its own will be enough.

Clearly there is more to learn about how and when information can be effective at improving learning outcomes in developing countries. Digging deeper into why these school-based approaches worked in some places but not others is one big question. Also, how effective could national or regional level information be at stimulating debate, and pressure on the school system, for improved performance? This is the approach used in PREAL’s national report cards in Latin America, or Pratham’s approach to monitoring learning levels in India or Uwezo’s Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda.

I look forward to seeing the results of studies that look into these issues in the future. In the meantime I know that I’ll be using information to monitor my children’s school’s performance.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons/ Aburke0128

Join the Conversation