Automation is heralding a renewed race between education and technology. However, the ability of workers to compete with automation is handicapped by the poor performance of education systems in most developing countries. This will prevent many from benefiting from the high returns to schooling.

Schooling quality is low

The quality of schooling is not keeping pace, essentially serving a break on the potential of “human capital” (the skills, knowledge, and innovation that people accumulate). As countries continue to struggle to equip students with basic cognitive skills- the core skills the brain uses to think, read, learn, remember, and reason- new demands are being placed.

In fact, the skills demanded by the labor market are evolving. Employers are demanding more flexible workers able to function at a high level. They are also demanding who can perform non-routine cognitive tasks. There is also a growing demand for social skills. There is a steady growth of jobs requiring high levels of social interaction in the labor force.

The limits of the East Asia growth model

In East Asia, we have reached the limits of the industrial model. What once worked for developed East Asia may not work for developing Asia. In fact, the technological revolution – or Fourth Industrial Revolution (#4IR) – and automation implies deskilling for many workers and a need for new skills for many.

Two essential parts of the East Asian growth story are trade reform and human capital. Policies that either incentivized exports or liberalized trade effectively activated a comparative advantage in low-cost, trainable labor. Korea, for example, had a GDP per capita in 1962 that was commensurate with many sub-Saharan African countries. But after a decade of labor intensive, export driven growth, real GDP per capita in Korea doubled.

The decline in the cost of automation technology and the breadth of tasks that are now able to be automated are expected to significantly disrupt labor markets in the coming decades. This poses significant challenges to developing countries.

Middle income countries tend to have the highest proportions of workers in automation-prone occupations (such as bookkeepers, mail carriers, tellers, among others). For low income countries, having low-cost, low-skill labor may no longer be a comparative advantage that they can exploit to achieve rapid economic growth as East Asia’s middle income countries did in the past.

The race between education and technology

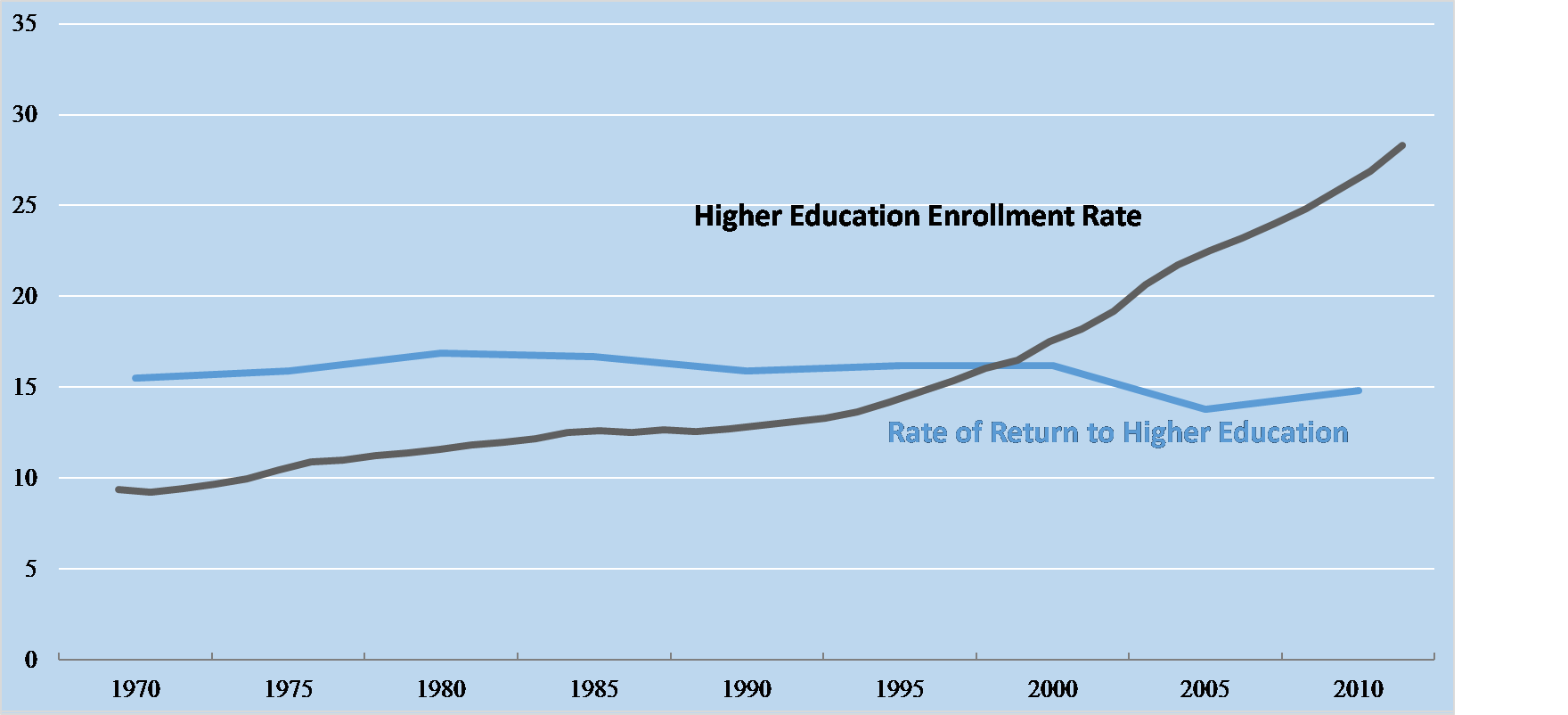

Nobel prize winning economist Jan Tinbergen in 1974 pointed to the skill-biasedness of technological progress with its consequences for income inequality. He also highlighted the pivotal role of education in mediating this relation.

During the 20th century, human capital acquisition boosted incomes and lowered inequality. However, the reverse has been true since about 1980. The educational slowdown that ensued was accompanied by rising inequality. Does this mean that education was losing its mediating effect?

This has profound implications for education systems, which find themselves in a constant struggle, indeed a race – a term coined by Tinbergen – to keep pace with the demand for skills and now an ever-growing change in the types of skills demanded.

What can be done?

Education can help, but countries will probably need a lot more of it, and it will need to be of higher quality, and facilitate access to new skills.

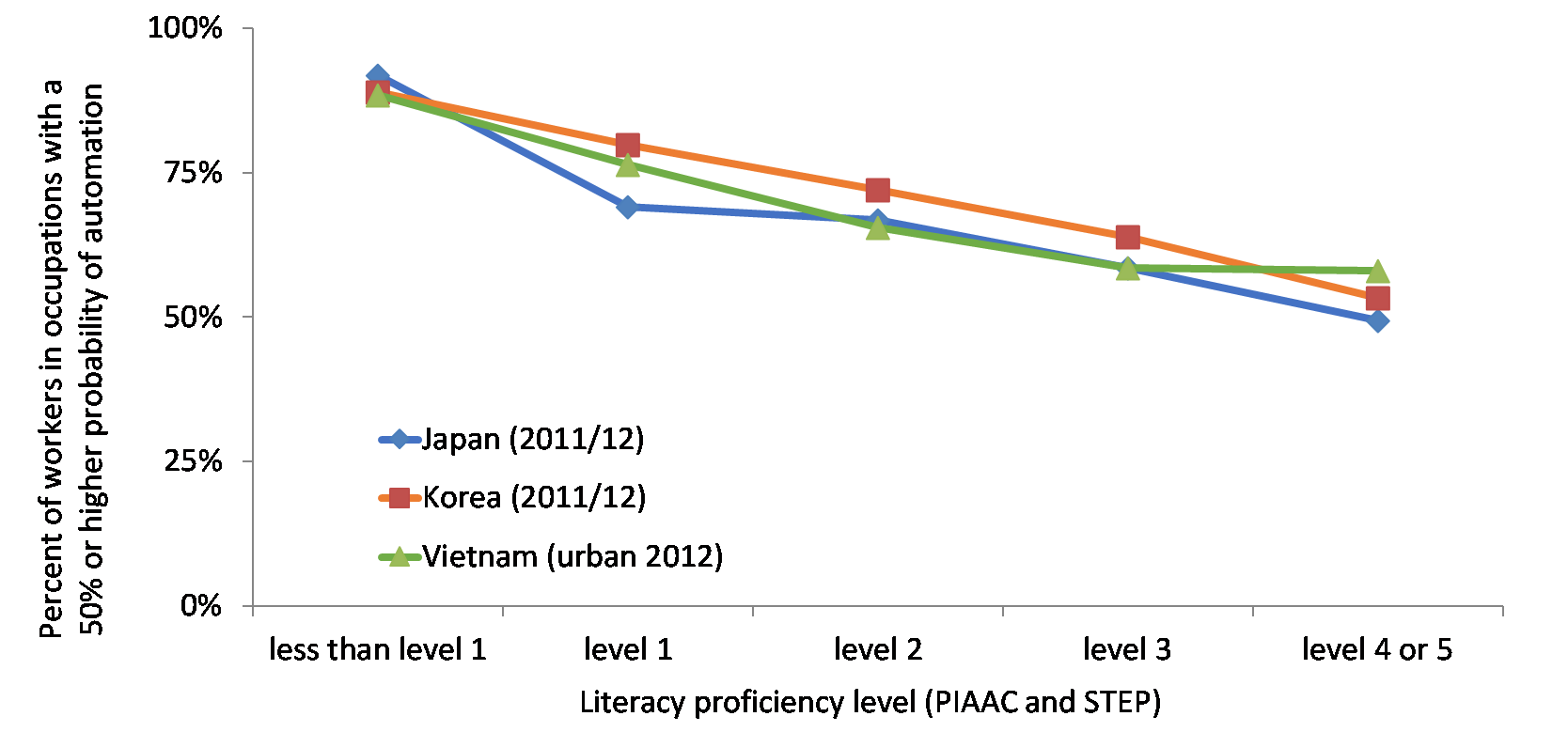

Post-secondary education graduates are at the lowest risk of losing to automation. Those with high levels of education are less likely to be in automation-prone occupations. Those with high literacy proficiencies are also at lower risk of losing their jobs to automation.

Economists studying the effects of automation are emphasizing the importance of “higher order soft skills” such as creativity and interpersonal skills. However, we believe that most countries still need to focus on getting the basics right.

The three biggest policy priorities that governments, investors and the development community should be doing to prepare for the future are:

- Focus on basic skills, early development, and measure and improve early reading;

- Give opportunities to workers to invest in relevant skills for the labor market that make them benefit from, and remain immune to, automation; and

- Use evidence from labor market returns to education to implement financial innovations and use future earnings to finance higher education

Find out more about World Bank Group Education on our website and on Twitter.

All our resources on skills and jobs are available here.

Join the Conversation