By educating girls, we reduce poverty, improve maternal and child health, prevent HIV and AIDS, and raise living standards for everyone. Despite the overwhelming evidence of the benefits of girls’ education, however, 37 million school-age girls around the world are not in class.

Factors such as poverty and distance from schools limit access to education, but even in situations where all children face such barriers, a gender disparity is evident. In India, among the socially marginalized groups designated as scheduled castes (SC) and scheduled tribes (ST), approximately 76% of SC and 81% of ST girls, as compared to 47% of SC and 61% of ST boys, do not complete secondary school.

A program called Samata (equality) aims to understand and overcome some of the reasons for this unequal access. A collaboration between Karnataka Health Promotion Trust (KHPT) and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), Samata is both a research study and a program to support girls from SC/ST communities to delay marriage and avoid entry into sex work by continuing in high school.

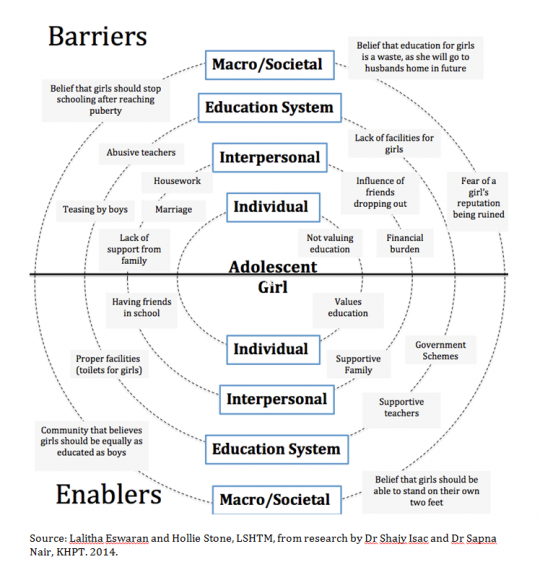

In exploratory studies, project researchers have interviewed adolescent girls, their parents and their teachers to document the barriers and enabling factors affecting girls’ education in north Karnataka. They learned that girls are expected to care for their younger siblings, do the household chores and often also provide financial support through manual labour or sex work.

Lack of adequate facilities, poor quality of teaching and physical abuse by teachers all discourage girls from attending school. From interviews, it is clear that many of the girls themselves do not value school and are influenced by peers who have dropped out and got married. Added to this is a pervasive normative pressure to marry girls early.

Students transition into secondary school around the time when girls reach puberty – the age at which parents fear that their daughters will experience ‘eve-teasing’ (sexual teasing) on their way to school or become involved in romantic relationships. The risk of a ‘bad reputation’ – together with family reliance on girls’ domestic labor and their earnings outside the home – encourages parents to withdraw girls at this crucial point in their schooling. This offers a good example of social and gender norms at work: Evidence of the benefits of education are unlikely to sway parents if they believe that everyone else in their community sees early marriage, for example, as the best way to ensure a daughter’s safety and future.

If information about the benefits of education will not, on its own, persuade communities to keep girls in school, what will work? Initial studies found that addressing structural and contextual factors has the potential to improve the rates of girls’ entry and retention in high school.

Based on these findings, Samata introduced a pilot intervention to reach 3,600 SC/ST girls in 69 high schools across 119 villages in Bagalkot and Bijapur Districts in north Karnataka. The project addresses the individual girl as well as the wider society and includes specific measures aimed at overcoming barriers and strengthening enabling factors. These include:

- providing special tuition, career counselling and leadership training to improve girls’ academic success and broaden their aspirations

- establishing reflection sessions for girls to share experiences and build solidarity and confidence

- sensitizing parents to value girls and recognize the importance of educating them

- linking families to government programs that provide incentives for educating girls

- using sports to encourage boys to respect girls and appreciate their rights

- training school management committees and school staff to institute measures to increase girls’ safety and academic success

- supporting community structures to understand the importance of girls’ education and take action

The Samata project, as well as its research and evaluation components, is supported by the World Bank Group, the government of Karnataka and – through the STRIVE consortium – UKaid / Department for International Development. The views expressed in this post do not necessarily reflect partners’ official policies.

Follow Samata on Twitter at @Samataforgirls

Follow the World Bank education team on Twitter at @WBG_Education

Related

Join the Conversation