In many ways, girls’ education is a success story in global development. Relatively simple changes in national policies – like making primary schooling free and compulsory – have led to dramatic increases in school enrollment around the world. In Uganda, for example, enrollment increased by over 60 percent following the elimination of primary school fees.

As more young people have enrolled in school, gaps in educational attainment between boys and girls have closed. According to UNESCO, by 2014, “gender parity (meaning an equal amount of men and women) was achieved globally, on average, in primary, lower secondary, and upper secondary education.”

Yet, more than 250 million children are not in school. Many more drop out before completing primary school. And many young people who attend school do not gain basic literacy skills. These challenges remain particularly acute for poor girls.

In a new paper, published in Population and Development Review, we explore recent progress in girls’ education in 43 low- and middle-income countries. To do so, we use Demographic and Health Survey data collected at two time points, the first between 1997 and 2007 (time 1), and the second between 2008 and 2016 (time 2).

This is what we discovered---

There has been global success on one very narrow indicator: gender parity in educational attainment. But a broader understanding of gender equality in education reveals how much work is yet to be done. Despite achieving gender equality globally, progress has stagnated, and girls continue to be at a disadvantage, in many countries.

A more nuanced approach is needed to monitoring progress in achieving gender equality in education. There needs to be more data on: each country’s stage in educational development, the levels of schooling at which gaps emerge and grow, gender-related barriers to school enrollment, progression, and learning, and gender differences in the return on investments in schooling.

Global trends can be unreliable

Choices about how progress is measured affect our ability to both understand challenges to achieving gender equality, and to design the most effective policies and interventions to address those challenges.

For more than a half century, low and middle-income countries have seen steady progress in increasing school enrollment and closing gender gaps. But global trends mask important variations between and within countries.

To understand patterns of progress across settings, we looked at changes in two indicators between time 1 and time 2 for countries in our study: educational attainment for girls and gender gaps. Out of 43 countries, only three (Comoros, Ghana and Sierra Leone) made substantial progress on both fronts. One third of countries (14) made no notable progress in either closing gender gaps or increasing educational attainment for girls. The remaining countries made progress in either closing gender gaps (17) or increasing attainment (6), but not both. Three countries (Jordan, Indonesia, Zimbabwe) had high levels of attainment and gender parity at time 1.

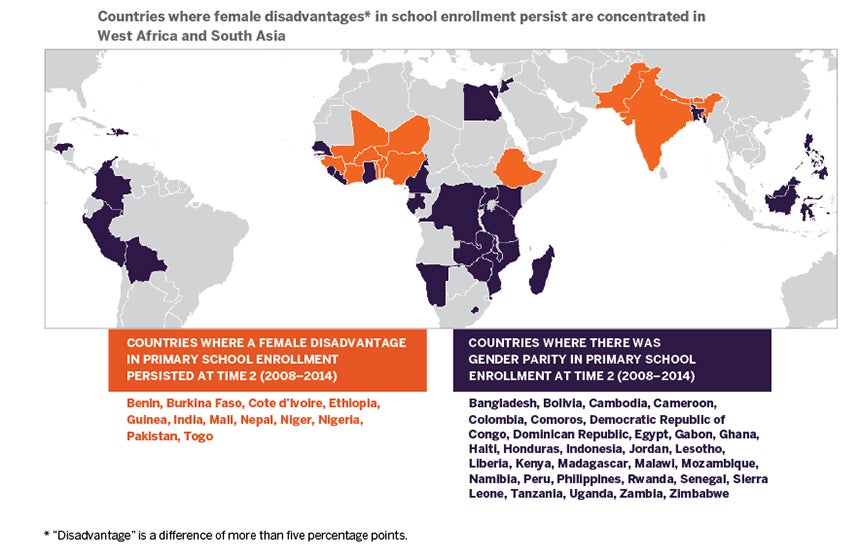

Perhaps even more telling, at time 2, girls in twelve countries - concentrated in West Africa and South Asia - were still at a disadvantage relative to boys in primary school enrollment.

Gender parity in educational attainment may mask other important inequalities

While still out of reach for many countries, gender parity in attainment is a low standard of success in education. We should not settle for “equal to boys” if both boys and girls are held back by subpar education.

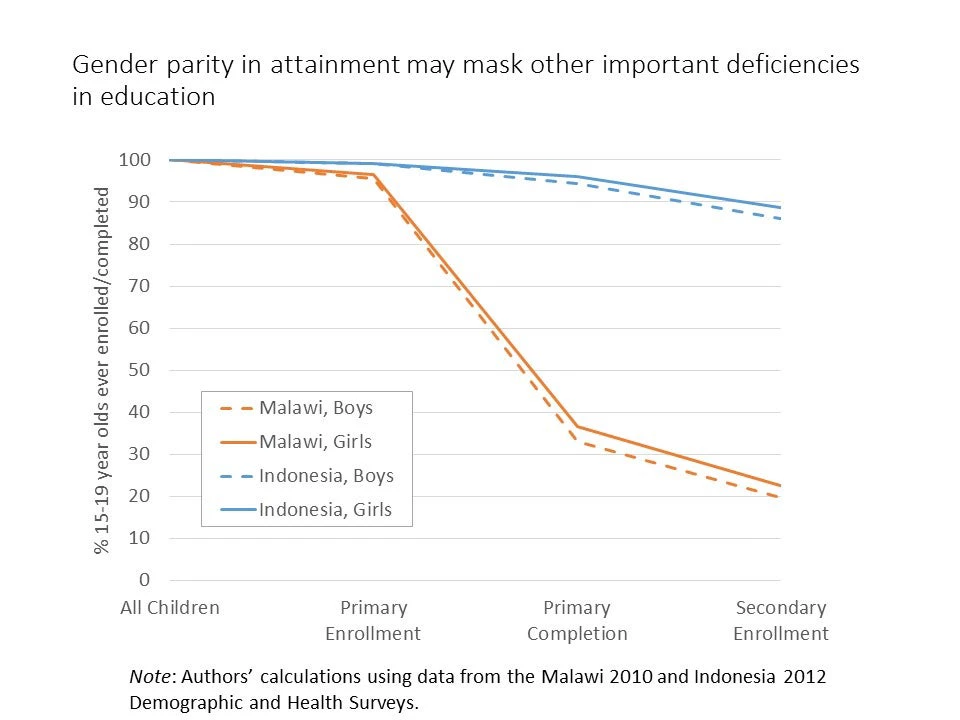

Consider countries where schooling levels are low for both girls and boys. In Malawi in 2010, nearly all young people are enrolled in school, but nearly two thirds dropped out before completing primary. Despite gender parity in schooling, a country such as Malawi, where fewer than 40% of girls – and boys – complete primary school, should not be considered a girls’ education success.

More broadly, low levels of school enrollment and completion undoubtedly reflect gender-related barriers, even in the absence of gender gaps. For example, high levels of primary school dropout may reflect unplanned pregnancies for girls, and pressure to earn an income for boys. As school enrollment levels increase in these countries, new disparities may well emerge.

In short, gender parity in attainment does not indicate success unless it occurs at high levels of school enrollment and attainment, as is the case in Indonesia in time 2.

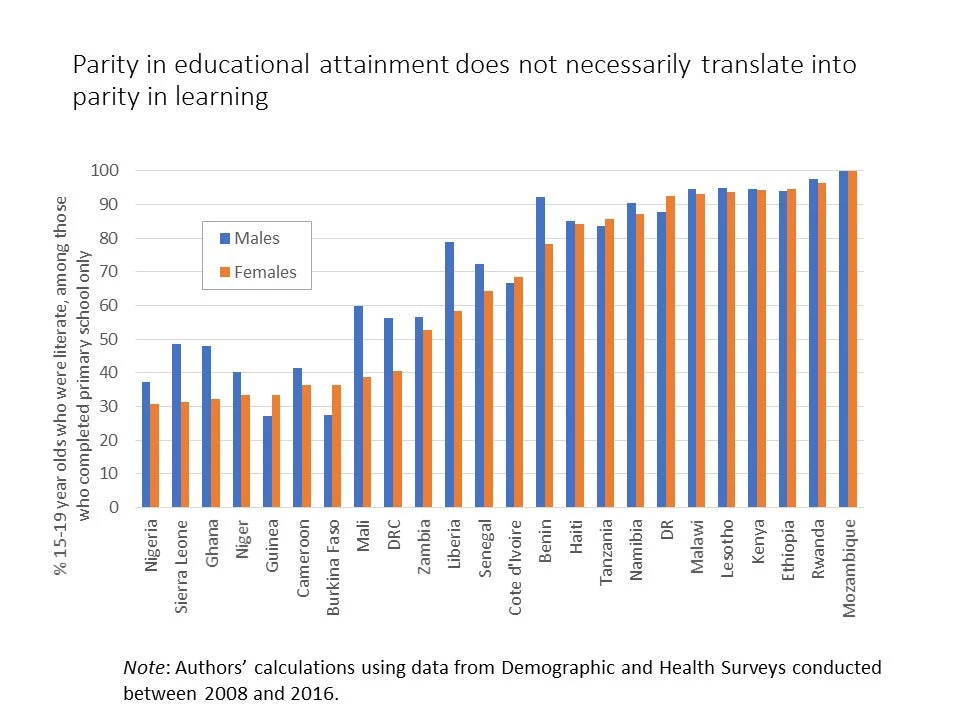

Gender parity in attainment does not necessarily translate into parity in learning

Even when gender parity is achieved at high levels of attainment, it may not translate into gender parity in learning. As other researchers have shown, many young people are not gaining even basic skills in school. In our study, we found stark gender differences in learning. Among 15-19-year-olds who had completed primary school but did not continue to secondary, boys were more likely than girls to have basic literacy skills in nine of 24 countries. In no country were girls substantially more likely to have basic literacy skills than boys.

Even more striking, in ten countries, including Cote d’Ivoire, Nigeria and Kenya, both girls and boys with a primary school education were even less likely to be able to read at time 2 than at time 1 – indicating a possible deterioration in the quality of schooling as enrollment has increased. As more children enter school, the challenge of ensuring they are gaining the skills they need for healthy transitions to adulthood becomes even greater.

Ultimately, the way we measure success for girls reflects how we value girls – and translates into how we invest in girls

In 1990, the Education for All movement set a narrow, but achievable, goal of universal primary school enrollment. Judged by that goal, enormous success has been realized. But judged by the goal of ensuring that all young people receive a quality education, as set out in the Sustainable Development Goals, much more work is required. Many young people, especially girls, are still not in school. Many of those who enroll in school drop out prematurely. And many who stay in school are not learning.

The global focus on gender parity fails to capture much of what is actually necessary to achieve gender equality. Raising our standards to include broader measurements of gender equality will enhance our efforts to accelerate progress for girls – and boys – around the world.

This is a guest post. The views & opinions expressed in any guest post featured on our site are those of the guest blogger/s and do not necessarily reflect the opinions & views of the World Bank as a whole.

Find out more about World Bank Education on our website and on Twitter.

Join the Conversation