It is estimated that more than 250 million school children throughout the world cannot read. This is unfortunate because literacy has enormous benefits – both for the individual and society. Higher literacy rates are associated with healthier populations, less crime, greater economic growth, and higher employment rates. For a person, literacy is a foundational skill required to acquire advanced skills. These, in turn, confer higher wages and more employment across labor markets .

Over the past decade, there has been growing evidence that shows that interventions for getting young children to read work. The mostly successful pilots should be brought to scale in all countries where early grade reading is an issue. To increase awareness of the need to do so, a global early skills assessment that tests reading abilities should be created and widely disseminated, serving as a global benchmark.

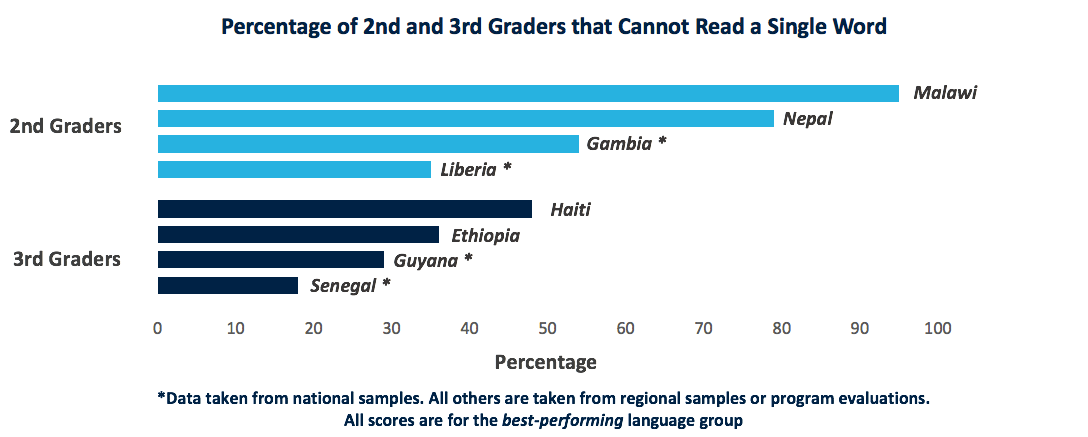

There is widespread illiteracy in the early grades

In order to address the high rates of child illiteracy that pervade in developing countries, we believe that education funding should be shifted towards early primary education reading initiatives.

Data from Early Grade Readings Assessments (EGRAs) show that huge swaths of populations in developing countries are not learning to read. Several cases illustrate how severe the problem is in some contexts: A program evaluation in Malawi found that 95 percent of second graders could not read a single word. Third graders do not necessarily perform much better. A regional sample in Haiti found that 48 percent of third grade students could not read a single word.

It is crucial that children learn to read in the early grades

In order to attain high literacy rates, children should be taught in the first few years of school. Research shows that it is more cost-effective to teach reading in early primary school than in higher levels. Cognitive research also shows that the optimal time to learn to read is the earlier grades. Shockingly, PISA test scores show that about half of the students that are finishing their primary education in middle-income countries are unable to comprehend the main message of basic texts. One way to address the illiteracy pandemic is through early grade reading interventions. Such interventions are typically geared towards first through third graders and are based on teacher training that improves the ability to teach literacy (for example, evidence-based, context-appropriate literacy curricula; simplified instructional content; follow-up coaching and support for teachers; supplementary instructional and reading materials; training and tools for student assessment).

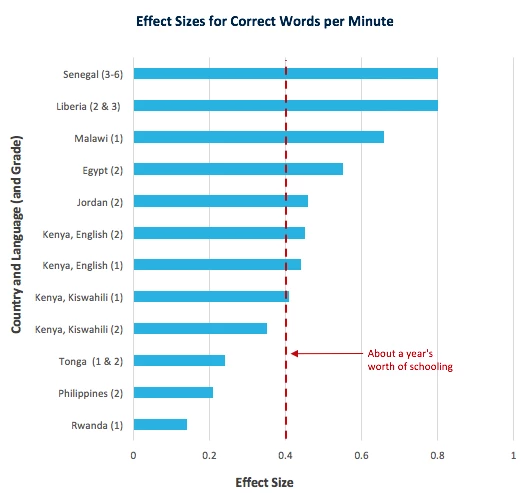

Early reading interventions have regularly proven cost-effective

Early reading interventions have had consistently large impacts, as is clear from the results from the impact evaluations from 13 countries that have that accrued over the past ten years from Egypt, Jordan, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Nepal, Papua New Guinea, Rwanda, Tonga, Rwanda, the Philippines, and Senegal. While the relative impacts vary, all early grade reading interventions almost always have major impacts on critical literacy indicators. The reading programs are cost-effective.

except for Malawi and Egypt and Jordan

Moving forward: Changing priorities and underscoring the problem

We know how to begin addressing this problem of high illiteracy rates – by scaling up early reading interventions. To do so, two steps should be taken.

- A global assessment should be created that tests students in the second to the fourth grade on basic reading skills. Such an assessment could be referred to as the Global Early Skills Assessment, or GESA. By highlighting the extent of illiteracy in simple terms (for example, the percentage of students that cannot read a single word) GESA may help give early grade reading the attention it deserves. It will also identify where the problem is most severe.

- Since people cannot take advantage of the high returns to secondary and tertiary education if they do not learn to read at a young age, education investments should be shifted heavily towards primary school. If there is a high rate of child illiteracy within a given country, public investment should prioritize primary education, especially results based on achieving early grade reading. Innovative financing approaches can be used to expand upper secondary and university education.

This blog is based on the report, The Case for Investing in Early Grade Reading.

Find out more about World Bank Group Education on our website and on Twitter.

Join the Conversation