Nepal needs to fix its budget process, remove hurdles to infrastructure development and cut down excess liquidiity.

At first glance Nepal’s economic fundamentals appear sound. Economic growth this year is expected to recover to 4.5%, after a lackluster FY13. On the fiscal and external fronts, indicators are well in the green. This year again, Nepal is likely to be the only country in South Asia to post a budget surplus (0.3% of GDP). Continued growth in revenue mobilization and higher grants will more than make up for the increase in government spending. In FY14, public debt is expected to fall below 30% of GDP, and Nepal’s risk of debt distress may fall from a “moderate” rating to “low”.

Unlike other South Asian countries, Nepal has remained largely unscathed by global monetary tightening, reflecting its limited integration into global financial markets as well as its healthy external balances. Nepali analysts often highlight the growing trade deficit as a cause for concern, but remittances (projected at over 30% of GDP) should push the current account to a comfortable surplus position of 2.4% of GDP.

The only apparent dark spot is inflation, which remains stubbornly high. With inflation close to double digits in January (year-over-year), it appears unlikely that the NRB’s target of 8.5% will be reached.

In short, Nepal appears to be doing well. Many European countries today can only dream of posting similar growth, fiscal or debt numbers. So what is the problem?

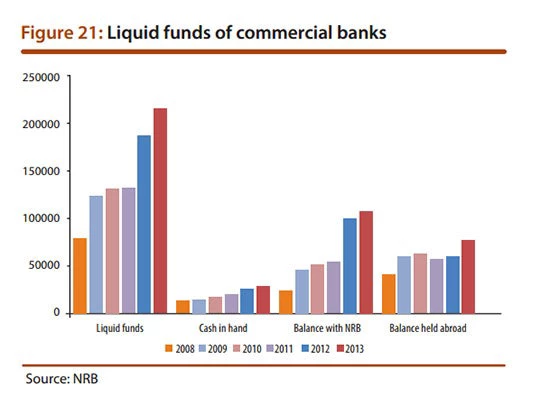

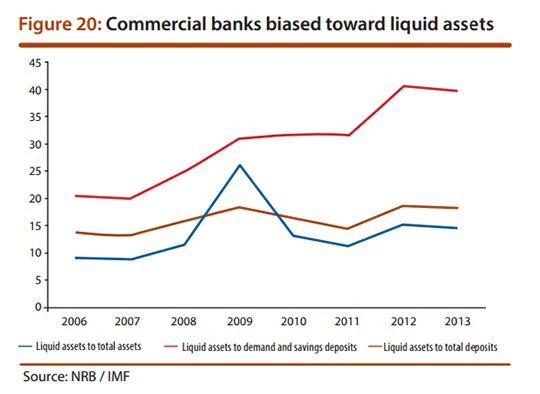

The problem is that Nepal is not making full use of the significant resources it has to hand, despite large needs and potential. The opportunity cost of one rupee sitting idly in the government’s Treasury account is not just one rupee, because that amount wisely spent could generate returns that are effectively forgone when unused. Now multiply that loss by 50 billion – the size of the treasury surplus at mid-year – and you get a sense of the lost opportunity to make Nepal’s significant fiscal space work for development. Alternatively, think of the vast amounts of liquidity that Nepali banks are currently holding or ‘parking’ at negligible rates of return (in fact real negative returns) in the form of Treasury Bills. The latest issue of NPR 19.5 billon was oversubscribed by NPR 44 million with rates below 0.1%.

To sum up, Nepal has ample resources, but the economy cannot use them in a productive manner to enhance the welfare of its citizens. Removing these bottlenecks should be at the forefront of the government’s agenda.

A first priority is to fix the budget process, which is in disarray. While dismal levels of spending in FY13 had been blamed on delayed adoption of the budget, the results for FY14 – when the budget was adopted relatively early – have also been disappointing. Nominal spending increased significantly in the first half of the year, but the ‘burn rate’ – the extent to which resources are effectively utilized – remained low at 37% for recurrent expenditures and only 13.5% for capital projects. The fate of National Pride projects is illustrative: at mid-year, only 13% of resources allocated to them had been used and several projects had zero or marginal disbursements.

A second priority is to remove obstacles to infrastructure development, most notably in energy and transportation. To take just one example, the NEA today is simply too weak financially to carry-out the vast investments that are needed to enhance transmission and distribution or to provide the necessary reassurance to private power producers that it, as the monopoly off-taker, will be able to pay for the energy that is supplied to it. Restoring the financial health of the NEA will not be easy, but it is imperative. To take another example, while the government has successfully extended the road network across much of Nepal, it needs to do much more to maintain the roads that it now has. One rupee spent on maintenance saves three rupees in rehabilitation costs down the line.

A third priority concerns the financial sector. Excess liquidity in the sector reveals Nepal’s weak investment climate, but also significant inefficiencies in the credit markets. The NRB recently initiated an in-depth diagnostic study of Nepal’s banks, and this study should provide invaluable information on their true health. But NRB has also directed banks to expand credit to “deprived” and “productive” sectors as well as to limit the spread that banks can maintain between deposit and lending rates. While these measures are well-intended, they could have unintended consequences in terms of financial sector stability and development. In our April edition of the Nepal Economic Update, we argue that the NRB’s intended objectives would be better served by removing the market inefficiencies that cause banks to curtail lending in the first place. Low hanging fruits include improving the services of the Credit Information Bureau, implementing a secured transactions framework and collateral registries, and revamping the debt enforcement and insolvency framework.

Nepal’s reform agenda is daunting, but the government has both the mandate –and the resources!- to carry it forward.

This article first appeared in The Kathmandu Post on April 22, 2014.

Join the Conversation