A malnourished child will face poorer outcomes as an adult.

That’s why improving nutrition, especially in the early stages of life, is critical .

The path toward better nutrition includes adequate maternal and child care, access to better sanitation facilities, health services, and naturally, nutritious foods .

But whether an individual consumes—or not—nutritious food is contingent upon a myriad of factors, ranging from the availability of certain foods, how convenient they can be turned into meals, or simply, if they meet consumers’ tastes.

But above all, the high cost of food remains the most critical barrier to proper nutrition and affects the poor more than the rich .

And in South Asia, where malnutrition persists in multiple forms, the cost of nutritious food is prohibitive .

Instead of merely analyzing what food costs, we specifically quantified what a good diet would cost— one that is not only nutritious but also balanced and promotes overall health.

To do so, we calculated the cost of an ideal diet based on national dietary guidelines (or food pyramid).

In 2017, the cost of meeting these guidelines was 187 rupees in Sri Lanka per adult per day, 87 rupees in Pakistan, and 45 afghanis in Afghanistan. This is roughly $1.2 to $2 per day.

In all these countries, we concluded that it is more expensive to meet national dietary guidelines than to eat the recommended amount of calories.

Since nutritious foods are expensive, many South Asians have poor diets: 49 percent of Sri Lankans and 58 percent of Pakistanis spend less on food than the cost of the recommended national dietary guidelines.

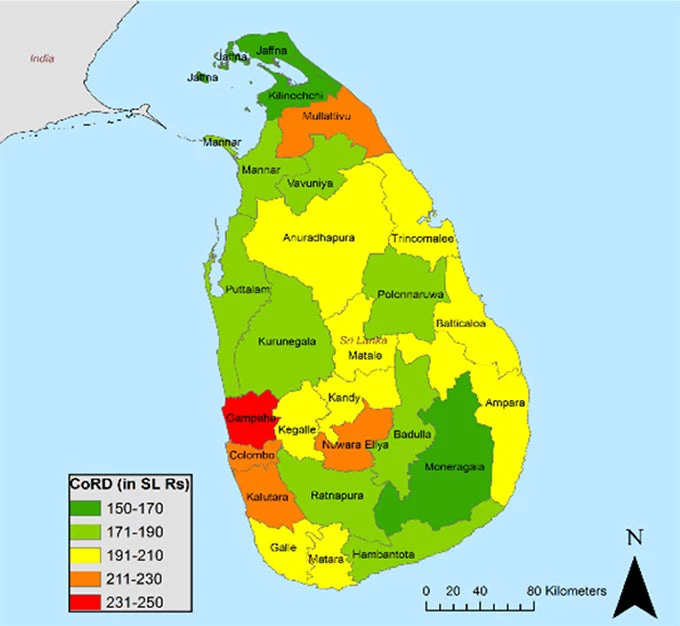

While a good diet is more expensive than a calorie-sufficient diet, its cost also varies within a country.

In Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, nutrient-rich perishable foods such as dairy and vegetables drive subnational cost disparities . Since perishable foods are more difficult to transport, their cost is subject to local production and availability.

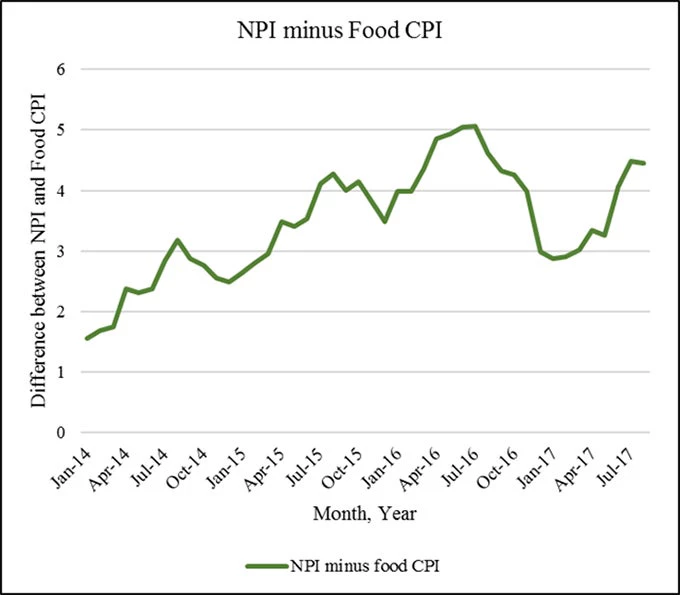

Yet what is worrying is that the cost of nutritious food has become increasingly prohibitive across South Asia .

Let us compare two food price indexes.

The first, the consumer food price index or food CPI, measures the change in the price of a typical food basket over time.

The second, called the nutritious food price index or NPI, measures the change in a nutritious food basket over time.

In both India and Pakistan, we found that the cost of a nutritious food basket increases faster than the cost of a typical food basket.

This trend is more pronounced in the lean season as food prices generally go up and the cost of a nutritious basket increases even more than a typical food basket.

Making nutritious food more affordable will involve a concerted effort from consumers, governments, and businesses

And central to that effort is to recognize the value of food first in terms of nutrients rather than calories.

True, food prices, like any other commodities, are determined by supply and demand.

On the demand side, consumers appear to eschew more expensive, nutritious foods for cheaper, less nutritious options.

While the poor might opt for cheaper foods because that is all they can afford, more well-off households follow a similar pattern.

While counterintuitive, this behavior stems from the fact that the benefits of a healthy diet occur much later in life, leading consumers who might otherwise afford them to underinvest in nutritious foods.

On the supply side, governments and firms have often favored cereals and other calorie-rich crops at the expense of nutritious, perishable foods.

Public subsidies in India and Pakistan have historically supported cereals.

At the same time, governments have made limited investments in storage and transport facilities that are needed to develop markets for perishable foods such as milk and vegetables.

Yet the public sector is not alone in the role they have to play to move from calories to nutrients.

Ultimately, as consumers purchase the bulk of their food from private markets, the private sector can and should play a crucial role in making nutritious foods available to all.

Join the Conversation