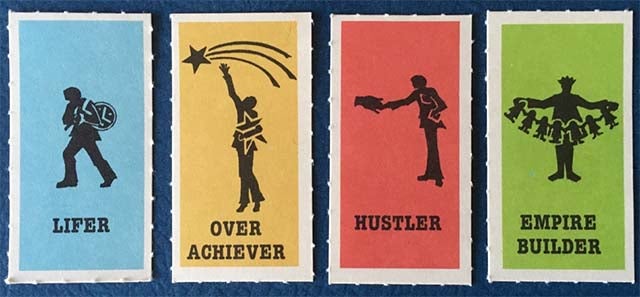

In the world of public sector bureaucracy, what type of bureaucrat are you?

In the board game 'Bureaucracy', you must assume the role of the ‘Lifer’, the ‘Over Achiever’, the ‘Empire Builder’, or the ‘Hustler’. Each character must use different tactics associated with their personality to rise up the ranks of the bureaucracy to achieve the position of director. For example, by amassing contacts, the Hustler can attempt a 'power play' on players above her in the hierarchy.

Though a rather tongue in cheek look at the everyday lives of so many of us working in large organizations, this board game has given me a different lens through which to understand the world of the public sector bureaucracy.

In a new World Bank Working Paper, 'Who Serves the Poor?', I use eight surveys of civil servants from six countries - Ethiopia, Ghana, Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan and the Philippines - to explore the characteristics and experience of life as a public official in the developing world. Evidence from these surveys implies that the board game isn’t too far from reality.

So what kind of bureaucrats are out there? Across the civil service, ‘Lifer’ seems the dominant personality type. In almost all of the countries surveyed, officials entered the service when they were in their mid-twenties, worked for a couple of years before joining their current organization and stay there for a decade or more. But staying doesn’t necessarily mean they are satisfied. Officials seem to get stuck, with half of those interviewed in Nigeria wanting to have been moved more. A dominant reason for promotion across the surveys is simply that the official has been around long enough, and it’s her turn for promotion.

That's not to say there isn't room for some ‘Over Achievers’. In Ghana, in particular, two-thirds of officials believe that ability is an important predictor of promotion. I found evidence consistent with the idea that ability is one route to success in the public sector, which echoes previous research. However, what it means to be an overachiever varies across settings. The surveys imply that there is a quite a bit of variation in the average level of education across and within civil services.

The other route to success would seem to be hustling, criss-crossing the civil service in an ascent to the top. This small minority of such officials is more likely to state that they had control over their career progression and that they had had ‘influence’ on securing their current posting. These officials, as in the board game, have more of a network, and use it to their advantage.

Hardest to identify are the ‘Empire Builders’. This might partly be because empires arise opportunistically. As one spot on the board game puts it, 'Crisis! Payoff: 3 staff, 3 civil service ratings'. One strategy is to proxy empire by the amount of time officials spend at work beyond their contracted hours, assuming that empires take investment. Though around 17% of staff are said to be working less than their contracted hours, a third work more, perhaps looking for their moment to empire build.

The surveys I study imply that these personality types are quite consistent across services, echoing some of the surprising similarities across bureaucracies. Perhaps it is these commonalities of bureaucracy that make it possible to have a board game whose rules are a 'Code of Bureaucratic Regulations' or 5 'stylized facts' of the civil service that I conclude the paper with. But I also find that the implied mix of personalities varies a lot, with lots of politics, favoritism and hustle in Nigeria and Pakistan contrasted with relatively frequent isolationism in the Philippines.

It’s crucial to understand the personalities that make up the developing world's public sectors. They are instrumental in ensuring the world's poorest people have access to public services. Understanding "the glamor and excitement of civil service inaction," as the 'Bureaucracy' board game tagline puts it, is central to securing services for the world’s poorest.

Tweet these:

New World Bank working paper explores the characteristics of life as a bureaucrat.

In the world of public sector bureaucracy, what type of bureaucrat are you?

It’s crucial to understand the personalities that make up the developing world's public sectors.

Join the Conversation