Yesterday, in Part I of this post, we argued the extant empirical evidence suggests that the conditions cause a substantial amount of the desired behavior change intended by CCT programs. In other words: the “substitution effect” due to the condition may well be larger than the “income effect” of the transfers. For example, in the case of the Malawi experiment, the income effect was responsible for less than half of the total impact on school enrollment.

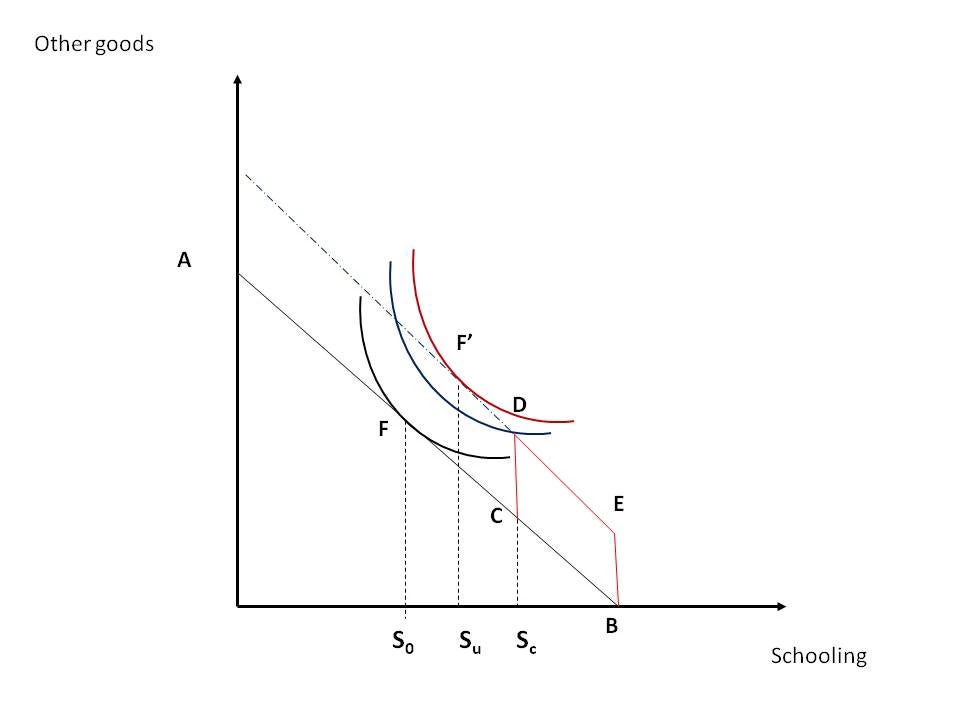

However, a greater enrollment rate (or even higher learning achievement) is not the same as higher welfare. Back in the simple world of our Figure 1, in fact, folks are better off at F’ (when they are given a UCT) even though they consume less schooling, than at D, where “attendance” is higher. That is, of course, as you would expect: people’s choice sets are larger when cash is given without conditions, and welfare cannot be lower when choice sets are larger.

Well, of course, Figure 1 may be a bad depiction of the real world, where people are not necessarily fully rational or perfectly informed; where different people in the household have their own agendas, and so on. For starters, CCTs were dreamt up by people thinking of long-term gains for these children, in terms of higher future wages and the like. The static picture in Figure 1 is really too simplistic. And yet, some of the new evidence from places like Malawi gives pause for thought. Another paper from the same experiment suggests that girls given UCT offers were significantly less likely to suffer from psychological distress in comparison to girls who were offered CCTs. Perhaps the trade-off between points D and F’ is not just a figment of the imagination of undergraduate textbooks. Higher educational attainment may indeed come at a cost in terms of current well-being, and some of these costs might have impacts that are as persistent in the long run as an extra year of schooling.

A cost in current well-being in order to reap future benefits is, of course, the essence of saving and investment behavior. The question is: why do we think that the individual’s own choice (at F’) is not optimal? There are a number of possible reasons: perhaps the individual making the decision at home (the father? both parents?) does not have the child’s long-term interests fully at heart. Perhaps those decision makers underestimate the actual future returns to schooling. Or perhaps there are positive spillovers from having more educated people around, so that long-term social welfare will improve more than it would have with UCTs. The point is: imposing a condition distorts behavior. That may be a good thing, if it helps internalize market or information failures, or principal-agent problems within the household. However, both the existence of those problems and the fact that CCTs are the optimal policy response remain to be convincingly established.

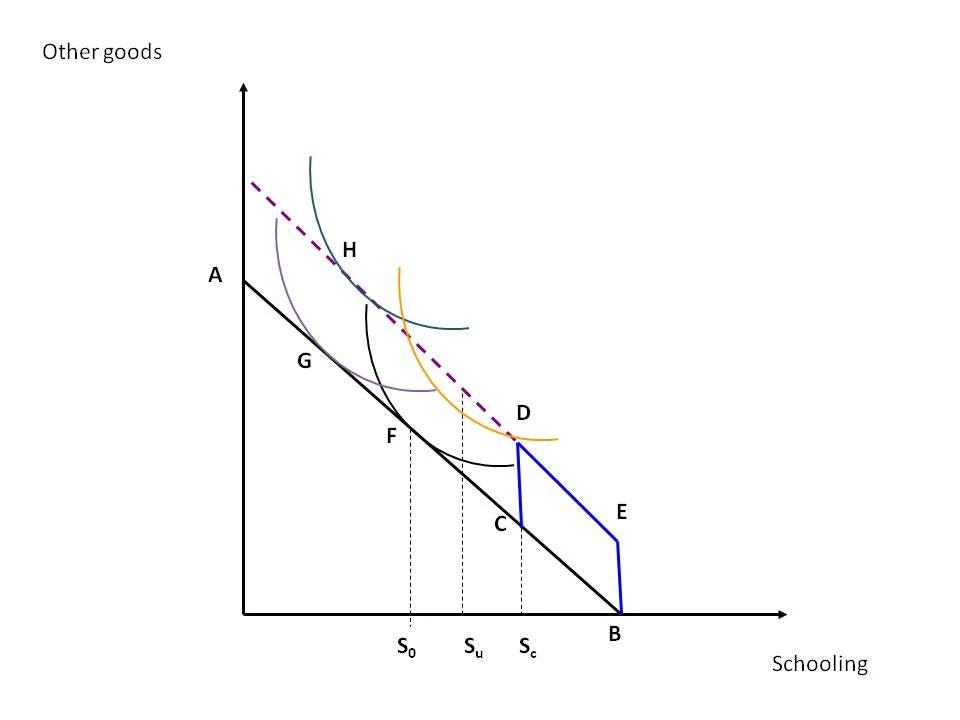

And there is more: The aforementioned trade-off focuses on compliers in the two programs – on gains and losses at points D and F’. However, there is a second source for potential UCT advantages relative to CCTs: we know that many families do not take up a CCT offer, i.e. children do not attend school even in the presence of a CCT offer. This may be because the target population is heterogeneous in terms of ability, distance to school, or other determinants of the opportunity cost of schooling. In Figure 2 below, unlike families that begin at F, those in a point such as G would not take up the CCT at all: they are better off at G than at D. Yet a UCT would move them to a point such as H. There, they might benefit from the increased age at marriage or delayed (potentially reduced) fertility found in Malawi. They, and their children, may be healthier in the long run. Or, who knows, they may even be able to set aside some of the extra money, to invest in (physical, rather than human) capital for the future, as this forthcoming paper (gated, working paper) by Gertler, Martinez, and Rubio-Codina suggests happened to transfer recipients in Mexico. Such trade-offs may well start stacking the deck in favor of reliable unconditional support to poor people in comparison to the CCT programs found in many countries. The trade-offs in this case will depend on the relative sizes of the complier and non-complier groups, and the long-term welfare effects from increased income among the non-compliers, and from increased schooling and learning among the compliers. An important point to remember is that the size of the non-complier group is larger than the compliers in many countries ranging from Cambodia to Malawi to Mexico.

CCT programs create incentives for individuals to change their behaviors by denying transfers to those who don’t satisfy the conditions. However, at least some of these individuals come from vulnerable households and are also in need of income support. UCTs to such households can improve important outcomes even though they are not as successful in improving schooling outcomes as CCTs. Hence, while CCT programs may be more effective than UCTs in obtaining the desired behavior change, they can also undermine the social protection dimension of cash transfer programs.

These trade-offs raise some interesting questions for the future of these cash transfer programs. Even when CCTs are correcting a market failure, they may only be a second- or third-best solution. If we could really pinpoint the externality (or information or agency failure) being addressed by the conditionality in CCT programs, could we design alternative programs that would provide unconditional cash alongside another cheap intervention designed to address the market failure? For example, if information or attitudes are part of the problem for school dropouts, would a UCT plus a social marketing campaign aided by communication scientists, psychologists, and behavioral economists perform better than a CCT by avoiding the trade-offs presented above? We believe that alternative designs should be squarely on the table when the next generation of cash transfer programs is being designed.

Join the Conversation