You may have heard about Tyler Cowen’s interview with Chris Blattman earlier this month. You would be forgiven, however, to have missed important news about cash transfers because, as far as I can tell, no one tweeted about this:

“BLATTMAN: We recently went back to some cash transfers that were given almost 10 years ago, following up a randomized control trial in Uganda in the north, and we’re just, in some sense, putting out those results.

What we found is, the initial result after two and four years was like other places seeing big advances in incomes. People get cash. They’re poor. They couldn’t invest in some of their ideas, but they had good ideas, and so they take off.

Now what we’ve seen is, essentially, they’ve converged with the people who didn’t get the cash. The people who didn’t get the cash have caught up because they saved and accumulated slowly and got up to the point where they have the same levels of success.

They converged to a good level. But this means that cash transfers are much more of a temporary acceleration than they are some sort of permanent solution to poverty.”

Now, I am not surprised at the finding. An increasing number of studies show short-term effects of cash transfers dissipating over time, at varying speeds of decay. But, more on that below… What did surprise me is that I had to read the transcript of the interview to find out about this new finding (no working paper yet, it seems, but here is an abstract). No one was tweeting about the massive four-year effects disappearing: remember that women almost doubled their income compared to the control group five years earlier. It’s not news that these effects are gone?

We are all guilty. If the quote had been about the durability of the effects of cash transfers – even at half of the short- and medium-term levels – many of my tweeps would be shouting it from the rooftops. Why? Because, we disseminate evidence that reinforces our view of the world, but choose to ignore or rationalize away stuff that does not. That may help to keep oneself sane these days, but a good public academic it does not make. Most of us think we’re better than that but we are fooling ourselves. Yes, many of you will politely retweet one of my posts about this or that hype about cash transfers, but deep down you know what you think: unconditional cash transfers are great and there is not a thing any researcher can do about it…

Another study, this one with a working paper, you would not have seen make the rounds on Twitter is the three-year follow-up of the original GiveDirectly experiment, following up on the nine-month impacts published a little over a year ago. Here is an excerpt from page 2:

“Comparing recipients households to non-recipients in distant villages, we find that recipients of cash transfers have 40% more assets than control households three years post transfer. This amount (USD 422 PPP) is equivalent to 60% of the initial transfer (USD 709 PPP). However, we do not find statistically significant across-village treatment effects on other outcomes. This difference could stem …from potential spillover effects at the village level. Indeed, non-recipient households in treatment villages show differences to pure control households on several dimensions. The point estimates suggest spillover households spend USD 30 PPP less than pure control households, or about 16% based on a pure control mean of USD 188 PPP, and score ˜0.25 SD less on an index of food security than pure control households. Spillover households also score ˜0.18 SD less on an index of psychological wellbeing than pure control households.”

Two months after being posted online, there are no newspaper articles, blog posts, or Twitter threads about the findings [update (3/27/2018): there was this short blog post from GiveDirectly, published on 2/14/2018]. In contrast, this working paper from the same experiment was made available simultaneously with an article in the Economist (I blogged about it here). Again, why isn’t GiveDirectly’s Twitter feed full of threads about this new paper? Say it with me: “Because, it’s dissonant to the song we want to be singing.” But, if we’re honestly going to talk about publication bias and transparency, we need to disseminate the successes and the failures with equal vigor. Otherwise, what are we doing here?

By the way, what’s the message you should be taking from the more recent paper by Haushofer and Shapiro (2018)? It may be worse than the short-term effects dissipating over time…

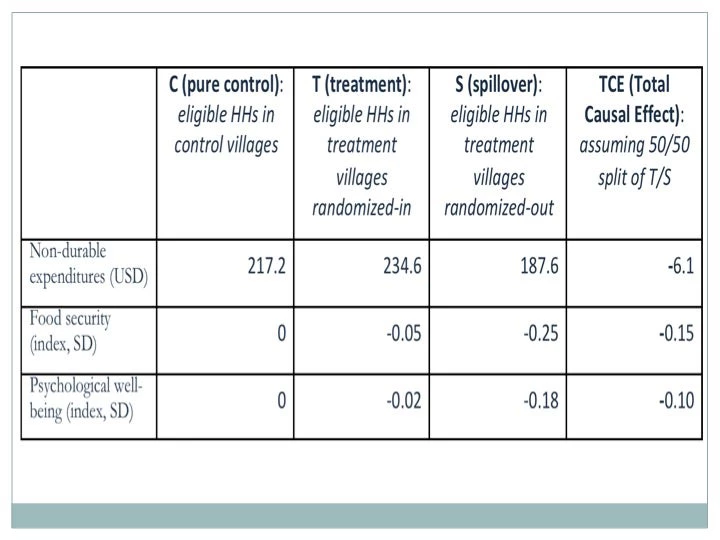

Here is a table I put together of the relative means of three outcomes at the three-year follow-up in three counterfactual groups (pure control, treatment, and spillover). As you can see in Table 5 of the paper, the treatment group is not doing better than the control group. Worse, the spillover group is not faring well at all – lower levels of expenditures, food security, and psychological wellbeing that are shown to be statistically significant in Table 7. Spillover effects are larger in absolute magnitude than the ITT effects, meaning that the total causal effect is negative in each case:

[The study design-minded readers, please refer to the methodological footnote below] [1]

Even in the most favorable interpretation of these new findings, however, the fact remains that there is no treatment effect of cash transfers on beneficiary households other than a sizeable increase in non-land assets, which are held mostly in improved roofs and livestock. This new paper and Blattman’s (forthcoming) work mentioned above join a growing list of papers finding short-term impacts of unconditional cash transfers that fade away over time: Hicks et al. (2017), Brudevold et al. (2017), Baird et al. (2018, supplemental online materials). In fact, the final slide in Hicks et al. states: “Cash effects dissipate quickly, similar to Brudevold et al. (2017), but different to Blattman et al. (2014).” If only they were presenting a couple of months later…

Cash transfers do have a lot of beneficial effects – depending on the target group, accompanying interventions, and various design parameters, but that discussion is for my next post…

The authors estimated program impacts by comparing T to S, instead of the standard comparison of T to C, in the 2016 paper because of a study design complication: researchers randomly selected control villages, but did not collect baseline data in these villages. The lack of baseline data in the control group is not just a harmless omission, as in “we lose some power, no big deal.” Because there were eligibility criteria for receiving cash, but households were sampled a year later, no one can say for certain if the households sampled in the pure control villages at follow-up are representative of the would-be eligible households at baseline.

So, quite distressingly, we now have two choices to interpret the most recent findings:

- We either believe the integrity of the counterfactual group in the pure control villages, in which case the negative spillover effects are real, implying that total causal effects comparing treated and control villages are zero at best. Furthermore, there are no ITT effects on longer-term welfare of the beneficiaries themselves - other than an increase in the level of assets owned. In this scenario, it is harder to retain confidence in the earlier published impact findings that were based on within-village comparisons – although it is possible to believe that the negative spillovers are a longer-term phenomenon that truly did not exist at the nine-month follow-up.

- Or, we find the pure control sample suspect, in which case we have an individually randomized intervention and need to assume away spillover effects to believe the ITT estimates.

Join the Conversation