I came back from a week off at the start of this year to find 7 referee requests from different journals waiting for me , of which I accepted 5 and turned down 2 – clearly some people are working quickly on that New Year’s resolution to send out their papers. Getting so many requests in the same week got me thinking about both how much I want to referee this year and what I can do to be a better referee.

How much to referee?

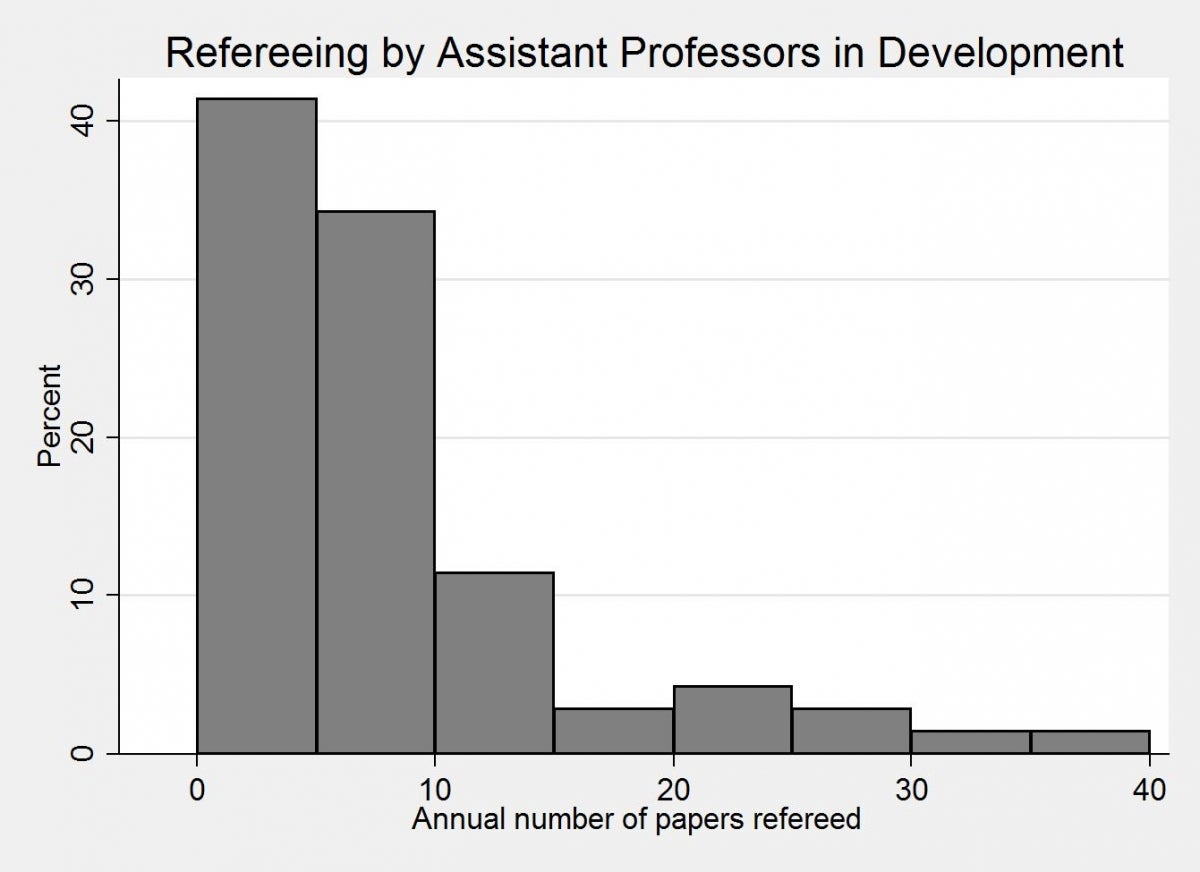

First, I thought I’d look back and take stock of how much I’d refereed the last couple of years. Looking through the folder where I store all my old reports, it seems I referred 37 papers last year, and 35 the year before. So about 3 a month on average. It is hard to know how this compares to the workload others are putting in since very little data seems to be available on how much we referee (although Dan Hamermesh has an interesting old (1994) Journal of Economic Perspectives article on refereeing which looks at issues such as who referees and how long they take to referee, but not how much they referee). In our survey last year of assistant professors in development, we did ask the amount people referee, with the mean being 7 papers and median 5 papers (see the figure below for the distribution).

Hamermesh reports that in his study, the average age for a referee was approximately 45, with requests to referee following an inverse U-shape in experience, peaking at 16 years post-Ph.D. So these assistant professors should be experiencing an increase in requests over their next few years. So when should you start turning papers down? In order to avoid free-riding, it seems polite to take requests from journals you’ve recently submitted to or published in, as well as those you plan to do so in the near future. Add to this papers at top journals directly on things you work on, those for journals you are on the editorial boards of (or would like to be in the future), revisions of papers you have already refereed once, and the numbers soon add up. If these numbers are adding up to more than 1 a month it might be time to start turning requests down. I don’t keep records of the papers I’ve turned down, but probably ended up turning down more papers than I refereed last year. My resolution for this year is to try and stay at a similar number of papers or less as the last two years.

How to referee?

There is no shortage of advice on how to referee – see, for example, the tips from Larry Katz in our recent Q&A with him; this old Marginal Revolution piece on how to be a good referee, which also links to this (a little dated) suggestion list. But we still all complain both about having to do reports, and about the reports we get. So here’s my tips which I’ll try to abide to in my own reports:

· Skim the paper within a couple of days receiving the request- my metro rides are good for this – you can quickly tell whether this is a paper that is well below the bar for some obvious reason and can be rejected as quickly as possible – it is bad enough as an author to have your paper to rejected, but certainly much more painful if you have had to wait months and months to hear this.

· Remember you are the referee, not a co-author: I love the “no revisions” policy at Economic Inquiry where you see whether the paper is interesting enough or not as is, without trying to get the author to rewrite it. I hear a lot that young referees in particular write very long reports (I received a 12 page report on one paper last year) which try and do way more than is needed to help make a paper clear, believable and correct. I think 2 pages or less is enough for most reports.

· Are we in a bad equilibrium where we are too harsh on each others’ papers: I’ve had conversations with several colleagues who are convinced that development economists are harsher reviewers of each other’s work than is the case in some other disciplines of economics. I think given the small number of papers on development published in top journals, a possible equilibrium is for people to think “journal A rejected my paper because if wasn’t generalizable enough/because of some other reason I didn’t think was a good one – but my paper was great – so I’ll certainly recommend rejection of this other development paper that I don’t think is as good as my one” – maybe we can all work on breaking this equilibrium and appreciating each others’ work a little more.

· Referee within one month – spend those few hours refereeing the paper now rather than waiting for the reminder emails: It is ridiculous how long our review processes are compared to sciences and finance. The Journal of Financial Economics has an interesting practice of publishing the names of the referees and their turnaround times (see here and here) – so we see many referees who provided reports within 28 days, while Andrea Buraschi of Chicago appears to be the slowest referee for 2011 at 218 days. It would be great if all journals did this, both as a way of naming and shaming those who take a long time, and as a way of providing greater transparency into the turnaround times.

Any other tips or anyone know of better data on how much people referee?

Join the Conversation