Co-authorship has become increasingly common in economics

, rising from 28 percent of publications in top journals in 1973 to 55% in 1993 and 79.6% in 2011. But

are people collaborating as much as they should, or do search frictions prevent productive collaborations from taking place?

In a new paper presented in the innovation session of the NBER summer institute, Kevin Boudreau and 6 co-authors (yes, itself an example of large collaboration involving both economists and medical researchers) examine this question through a field experiment with researchers from Harvard Medical School.

The Experiment

I was surprised to learn that Harvard Medical School and its 17 affiliated hospitals and research institutes collectively employ 11,000 faculty. In order to promote early-stage research, the school competitively awards pilot grants of $50,000 to enable researchers to generate the preliminary data needed for larger grant applications to outside funders.

The experiment takes place in the context of a call for grants centered around proposals to use advanced imaging technologies to address unmet clinical needs. Such research requires both expertise in imaging technology, as well as knowledge of the health problems to which they can be applied, which is often met by people with different specializations collaborating together.

The population for the experiment was then 402 clinical and imaging researchers who had indicated interest in applying for these grants. As part of the grant application process, potential applicants had to participate in a research symposium where they would find out about grant rules and administration, learn about the advanced technologies behind the grant, and attend an information-sharing session. These 90 minute sharing sessions were held in break-out rooms with about 30 researchers in them, where each researcher had an interactive poster presentation to the others in the room, along with time to chat among themselves.

The experiment then proceeded as follows:

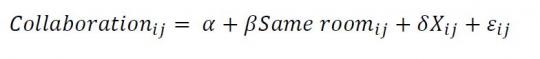

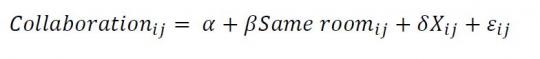

The authors estimate the following model for all possible pairings of individuals i and j from among the 402 participants:

Where the question of interest is whether being randomly assigned to be in the same break-out room as another person makes you more likely to collaborate on a subsequent grant proposal with them.

The majority (66%) of applications were for a collaboration with other people who had not been to the symposium. The authors then find that:

My thoughts

On the substantive side, I was somewhat surprised by these results, given the relative low-intensity of the intervention. I’ve recently worked on a couple of interventions intended to reduce search frictions ( one for migrants in the Philippines, and one for job-seekers in Jordan (to be blogged about soon)), and in both cases have discovered there is a reason the market hasn’t reduced these search frictions, with it being very hard to find effects of efforts to do so. So the fact that being in a room with someone for a 90 minute session can influence whether you end up working with them is interesting.

On the impact evaluation side, trying to measure the effects of pairings raises a couple of important issues which the paper doesn’t completely deal with:

This paper does highlight the importance of face-to-face interaction in spurring collaborations. So use it to justify attending that next conference, or at least as an excuse to have lunch with people from another building…

In a new paper presented in the innovation session of the NBER summer institute, Kevin Boudreau and 6 co-authors (yes, itself an example of large collaboration involving both economists and medical researchers) examine this question through a field experiment with researchers from Harvard Medical School.

The Experiment

I was surprised to learn that Harvard Medical School and its 17 affiliated hospitals and research institutes collectively employ 11,000 faculty. In order to promote early-stage research, the school competitively awards pilot grants of $50,000 to enable researchers to generate the preliminary data needed for larger grant applications to outside funders.

The experiment takes place in the context of a call for grants centered around proposals to use advanced imaging technologies to address unmet clinical needs. Such research requires both expertise in imaging technology, as well as knowledge of the health problems to which they can be applied, which is often met by people with different specializations collaborating together.

The population for the experiment was then 402 clinical and imaging researchers who had indicated interest in applying for these grants. As part of the grant application process, potential applicants had to participate in a research symposium where they would find out about grant rules and administration, learn about the advanced technologies behind the grant, and attend an information-sharing session. These 90 minute sharing sessions were held in break-out rooms with about 30 researchers in them, where each researcher had an interactive poster presentation to the others in the room, along with time to chat among themselves.

The experiment then proceeded as follows:

- Applicants applied for the program, and were told they needed to attend the research symposium on one of three days, indicating whether there were any days they couldn’t attend.

- Applicants were then randomly assigned to one of the 12 break-out sessions (4 per day), taking account of any constraints on them attending.

- They attended the sessions, met with the others and presented their ideas.

- Shortly afterwards, participants got an email invitation to submit applications for the pilot grants, along with a complete list of the participants from all three nights of the symposia, and all information detailed on all posters in the breakout rooms. The intention was to provide identical information to all participants about potential collaborators apart from any information specifically received in the break-out room discussions.

- They could then apply for the grants, which required a principal investigator and at least one co-investigator, and required at least one person on the grant to have attended the research symposium.

- The authors then look to see whether randomly being matched in a break-out room with another researcher makes you more likely to collaborate with them in applying for a grant.

The authors estimate the following model for all possible pairings of individuals i and j from among the 402 participants:

Where the question of interest is whether being randomly assigned to be in the same break-out room as another person makes you more likely to collaborate on a subsequent grant proposal with them.

The majority (66%) of applications were for a collaboration with other people who had not been to the symposium. The authors then find that:

- Treatment (being randomly assigned in the same room) raises the likelihood of a pair collaborating from 0.16 to 0.28 percent (a 75 percent increase), which is significant at the 10 percent level.

- In terms of magnitude, this is about one-third the associated effect (from the X’s) of working in the same hospital or working in the same clinical area as another researcher, but two orders of magnitude smaller than the associated effect on collaboration of having previously co-authored together.

My thoughts

On the substantive side, I was somewhat surprised by these results, given the relative low-intensity of the intervention. I’ve recently worked on a couple of interventions intended to reduce search frictions ( one for migrants in the Philippines, and one for job-seekers in Jordan (to be blogged about soon)), and in both cases have discovered there is a reason the market hasn’t reduced these search frictions, with it being very hard to find effects of efforts to do so. So the fact that being in a room with someone for a 90 minute session can influence whether you end up working with them is interesting.

On the impact evaluation side, trying to measure the effects of pairings raises a couple of important issues which the paper doesn’t completely deal with:

- The first is how to deal with standard errors in the regression. The authors use standard Eicker-White (robust) standard errors, although claim the results are similar with grouped dyadic standard errors (if so, I’m not sure why they prefer the robust errors).

- The more important concern is how to think about treatment effects in this context. The standard assumption for causal inference here is the stable unit treatment value assumption (SUTVA) which assumes that the treatment status of any individual does not affect the potential outcomes of other units. But this seems unlikely to hold here. For example, suppose I am randomly assigned to be in the same room as Berk. Whether or not we collaborate after I see Berk’s poster may depend on whether Markus was also randomly assigned to the same room and I end up seeing his cooler project and deciding to work with him instead. If this is the case, then my potential outcomes may depend on the whole vector of treatment allocations for every other researcher. This isn’t an area I have worked on, so I’m not sure what current best practice is when attempting to look at randomization within networks where the whole purpose is to generate interactions between individuals, and where the number of collaborations any one researcher can do is necessarily limited.

This paper does highlight the importance of face-to-face interaction in spurring collaborations. So use it to justify attending that next conference, or at least as an excuse to have lunch with people from another building…

Join the Conversation