Alternative title (since that one sounds a bit 1984 doublespeak-ish): Can Governments Leverage Tax Morale to Increase Tax Compliance?

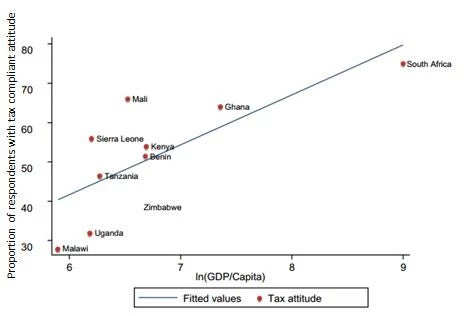

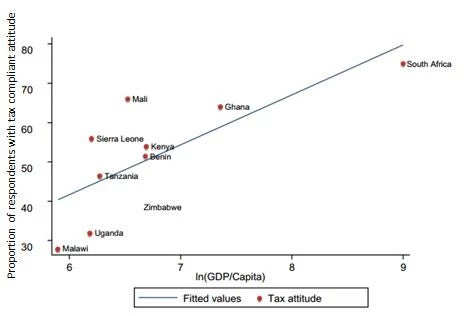

A recent paper ( Ali et al. 2014) examined “tax compliant attitudes” in a number of African countries, using Afrobarometer data. Individuals were coded as tax-compliant if, when asked how they felt about people not paying taxes on their income, they replied that it was “wrong and punishable” as opposed to “not wrong at all” or “wrong, but understandable”. In the figure from the paper (below), you can that several countries don’t have very tax compliant attitudes. And if you believe that people are more likely to talk tax compliant than to act tax compliant, this is likely an upper bound on actual tax compliance.

from Ali et al. 2014

For four countries (South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda), the authors summarize the answer that respondents give to why some people (not you, of course) evade taxes. In all four countries, the most common responses are that taxes are too high or are unaffordable, but a significant number of individuals also say that the tax system is unfair (8-11% of respondents, across countries), that the government wastes or steals taxes (8-11%), or that public services are poor (9-16%).

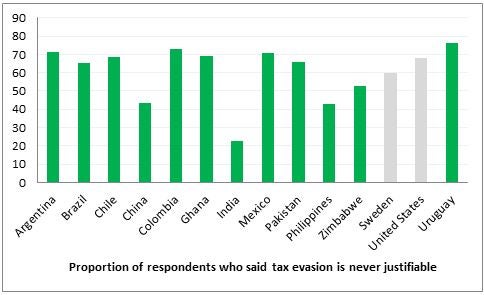

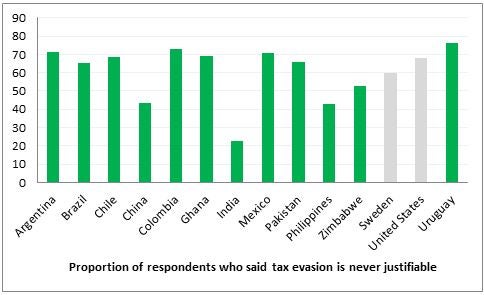

The latter three motives in particular relate to “tax morale,” which Luttmer & Singhal (L&S) define as “non-pecuniary motivations for tax compliance as well as factors that fall outside the standard, expected utility framework” in their recent, extremely helpful critical review of the evidence (upon which the rest of this post relies heavily). They show that paying taxes is driven by much more than individuals’ simple calculation of the benefits of tax evasion (more money now) minus the costs of tax evasion (probability of getting caught times the penalty), all adjusted for risk aversion. (This model builds on Becker’s model of crime, which was adapted to taxes by Allingham & Sandmo in 1972 and has been used for many years.) Indeed, a quick look at the World Values Survey data for whether it’s justifiable to cheat on taxes if you have a chance – for a convenience sample of developing countries with a couple of high-income comparators – shows that lot of people feel strongly about paying taxes.

from World Values Survey – my calculations

L&S break tax morale into five mechanisms:

For intrinsic motivation, appealing to taxpayers’ (or non-payers’) civic duty, field experiments thus far seem not to have been very effective. One example is this intervention in Austria, which sent a letter including the language “Those who do not conscientiously register their broadcasting receivers not only violate the law, but also harm all honest households. Hence, registering is also a matter of fairness.” No impact.

For reciprocity, the evidence is mixed. An intervention in Minnesota sent a letter concluding “So when taxpayers do not pay what they owe, the entire community suffers.” A study in Germany encouraged payment of a church tax with a letter including the line “With the local church tax you notably fund the work of your parish.” In some of the only work from developing countries, an intervention in Argentina included a message in the tax bill highlighting the “number of streetlights, and the number of water and sewerage connections installed by the local government” in the previous six months. None of these interventions had a significant impact on compliance.

On the other hand, a letter to taxpayers in Norway (specially selected among those likely to have misreported in previous years) included either a fairness appeal or a “public service” appeal (“Your tax payment contributes to the funding of publicly financed services in education, health and other important sectors of society”): The pooled effect of these two appeals relative to a neutral letter was significant on the level of reported income. Another study, in the UK, found that a public service appeal decreased tardiness in payment.

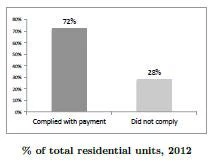

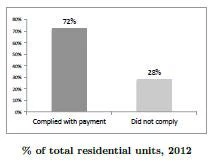

For peer effects and social influences, notifying taxpayers in generally high-compliance contexts (e.g., the USA) that everyone else is paying their taxes does not seem to have been influential, perhaps because people already know that. In a lower compliance environment, a study in Peru involved sending a letter saying that “the large majority of residents in our district comply voluntarily with the property tax,” accompanied by the figure below, as well as another, similar letter and figure. In that case, the impact was sizeable and significant; survey data revealed that recipients updated their beliefs about how much other people pay in taxes positively (i.e., compliance was relatively low, but people thought compliance was even lower).

from Del Carpio 2014

I’ll leave long-term cultural factors out of this discussion, although there is some interesting evidence that they matter. For information imperfections, the above Peru study found a strong effect of a very simple letter reminding residents to pay (“We remind you that the second installment of your 2013 property tax is due on May 31”).

What do we take away? First, appeals to morality and reciprocity have a pretty mixed track record (not negative; just mixed). Second, simple reminders can sometimes have a significant impact (as in Peru). Third, keep in mind – as Luttmer & Singhal highlight – that enforcement is likely to be the primary driver, and then tax morale can affect compliance within a context of enforcement. (Let’s not get so excited about nudges that we forget the environment within which those nudges work.)

Fourth, one of the weaknesses of these interventions may be the power of the intervention: Maybe a line in a letter isn’t enough to change people’s sense of morality or social norms. It would be interesting to see whether media campaigns to reinforce social norms (like these billboards in Italy) have more power. Finally, the evidence – especially for low- and middle-income countries – is pretty thin. I counted two studies (taking place in Peru and Argentina -- each with more arms than I've discussed here). So there is much room to learn. Baseline tax compliance, tax enforcement, and beliefs about how taxes are used may be very different in low- and middle-income contexts relative to high-income country contexts, so it makes sense to keep an open mind as to what might work.

Bonus reading

A recent paper ( Ali et al. 2014) examined “tax compliant attitudes” in a number of African countries, using Afrobarometer data. Individuals were coded as tax-compliant if, when asked how they felt about people not paying taxes on their income, they replied that it was “wrong and punishable” as opposed to “not wrong at all” or “wrong, but understandable”. In the figure from the paper (below), you can that several countries don’t have very tax compliant attitudes. And if you believe that people are more likely to talk tax compliant than to act tax compliant, this is likely an upper bound on actual tax compliance.

from Ali et al. 2014

For four countries (South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda), the authors summarize the answer that respondents give to why some people (not you, of course) evade taxes. In all four countries, the most common responses are that taxes are too high or are unaffordable, but a significant number of individuals also say that the tax system is unfair (8-11% of respondents, across countries), that the government wastes or steals taxes (8-11%), or that public services are poor (9-16%).

The latter three motives in particular relate to “tax morale,” which Luttmer & Singhal (L&S) define as “non-pecuniary motivations for tax compliance as well as factors that fall outside the standard, expected utility framework” in their recent, extremely helpful critical review of the evidence (upon which the rest of this post relies heavily). They show that paying taxes is driven by much more than individuals’ simple calculation of the benefits of tax evasion (more money now) minus the costs of tax evasion (probability of getting caught times the penalty), all adjusted for risk aversion. (This model builds on Becker’s model of crime, which was adapted to taxes by Allingham & Sandmo in 1972 and has been used for many years.) Indeed, a quick look at the World Values Survey data for whether it’s justifiable to cheat on taxes if you have a chance – for a convenience sample of developing countries with a couple of high-income comparators – shows that lot of people feel strongly about paying taxes.

from World Values Survey – my calculations

L&S break tax morale into five mechanisms:

- Intrinsic motivation (Pride at fulfilling your civic duty; guilt associated with cheating)

- Reciprocity (I pay my taxes, and the government provides education, roads, and security)

- Peer effects and social influences (Everyone else is paying, so I should too)

- Long-run cultural factors (I’m an [insert nationality], and we pay our taxes!)

- Information imperfections (People misestimate the likelihood of getting audited, or they forget)

For intrinsic motivation, appealing to taxpayers’ (or non-payers’) civic duty, field experiments thus far seem not to have been very effective. One example is this intervention in Austria, which sent a letter including the language “Those who do not conscientiously register their broadcasting receivers not only violate the law, but also harm all honest households. Hence, registering is also a matter of fairness.” No impact.

For reciprocity, the evidence is mixed. An intervention in Minnesota sent a letter concluding “So when taxpayers do not pay what they owe, the entire community suffers.” A study in Germany encouraged payment of a church tax with a letter including the line “With the local church tax you notably fund the work of your parish.” In some of the only work from developing countries, an intervention in Argentina included a message in the tax bill highlighting the “number of streetlights, and the number of water and sewerage connections installed by the local government” in the previous six months. None of these interventions had a significant impact on compliance.

On the other hand, a letter to taxpayers in Norway (specially selected among those likely to have misreported in previous years) included either a fairness appeal or a “public service” appeal (“Your tax payment contributes to the funding of publicly financed services in education, health and other important sectors of society”): The pooled effect of these two appeals relative to a neutral letter was significant on the level of reported income. Another study, in the UK, found that a public service appeal decreased tardiness in payment.

For peer effects and social influences, notifying taxpayers in generally high-compliance contexts (e.g., the USA) that everyone else is paying their taxes does not seem to have been influential, perhaps because people already know that. In a lower compliance environment, a study in Peru involved sending a letter saying that “the large majority of residents in our district comply voluntarily with the property tax,” accompanied by the figure below, as well as another, similar letter and figure. In that case, the impact was sizeable and significant; survey data revealed that recipients updated their beliefs about how much other people pay in taxes positively (i.e., compliance was relatively low, but people thought compliance was even lower).

from Del Carpio 2014

I’ll leave long-term cultural factors out of this discussion, although there is some interesting evidence that they matter. For information imperfections, the above Peru study found a strong effect of a very simple letter reminding residents to pay (“We remind you that the second installment of your 2013 property tax is due on May 31”).

What do we take away? First, appeals to morality and reciprocity have a pretty mixed track record (not negative; just mixed). Second, simple reminders can sometimes have a significant impact (as in Peru). Third, keep in mind – as Luttmer & Singhal highlight – that enforcement is likely to be the primary driver, and then tax morale can affect compliance within a context of enforcement. (Let’s not get so excited about nudges that we forget the environment within which those nudges work.)

Fourth, one of the weaknesses of these interventions may be the power of the intervention: Maybe a line in a letter isn’t enough to change people’s sense of morality or social norms. It would be interesting to see whether media campaigns to reinforce social norms (like these billboards in Italy) have more power. Finally, the evidence – especially for low- and middle-income countries – is pretty thin. I counted two studies (taking place in Peru and Argentina -- each with more arms than I've discussed here). So there is much room to learn. Baseline tax compliance, tax enforcement, and beliefs about how taxes are used may be very different in low- and middle-income contexts relative to high-income country contexts, so it makes sense to keep an open mind as to what might work.

Bonus reading

- Joana Naritomi’s post on Development Impact evaluating a Brazilian government program providing tax rebates and lottery tickets to consumers who collect receipts from businesses (obligating the businesses to issue electronic receipts and accurately report income).

- David McKenzie’s post on Development Impact on what kinds of information interventions are likely to have impact.

Join the Conversation