Volatility in financial markets gets wide attention in the public eye. Less noticed is what we in the development world call macroeconomic volatility—faster-than-desired swings in the broad forces which shape an economy. Think investment, government spending, interest rates, foreign trade and the like.

There are three key questions to analyze: how do these forces interact, what is their effect on overall growth, and what policies are best to follow? All this is of more than academic interest: macroeconomic volatility can bring substantial hardships to millions of people

In this blog post and others to follow, we’ll offer some answers, with a focus on the small island nations of the eastern Caribbean.

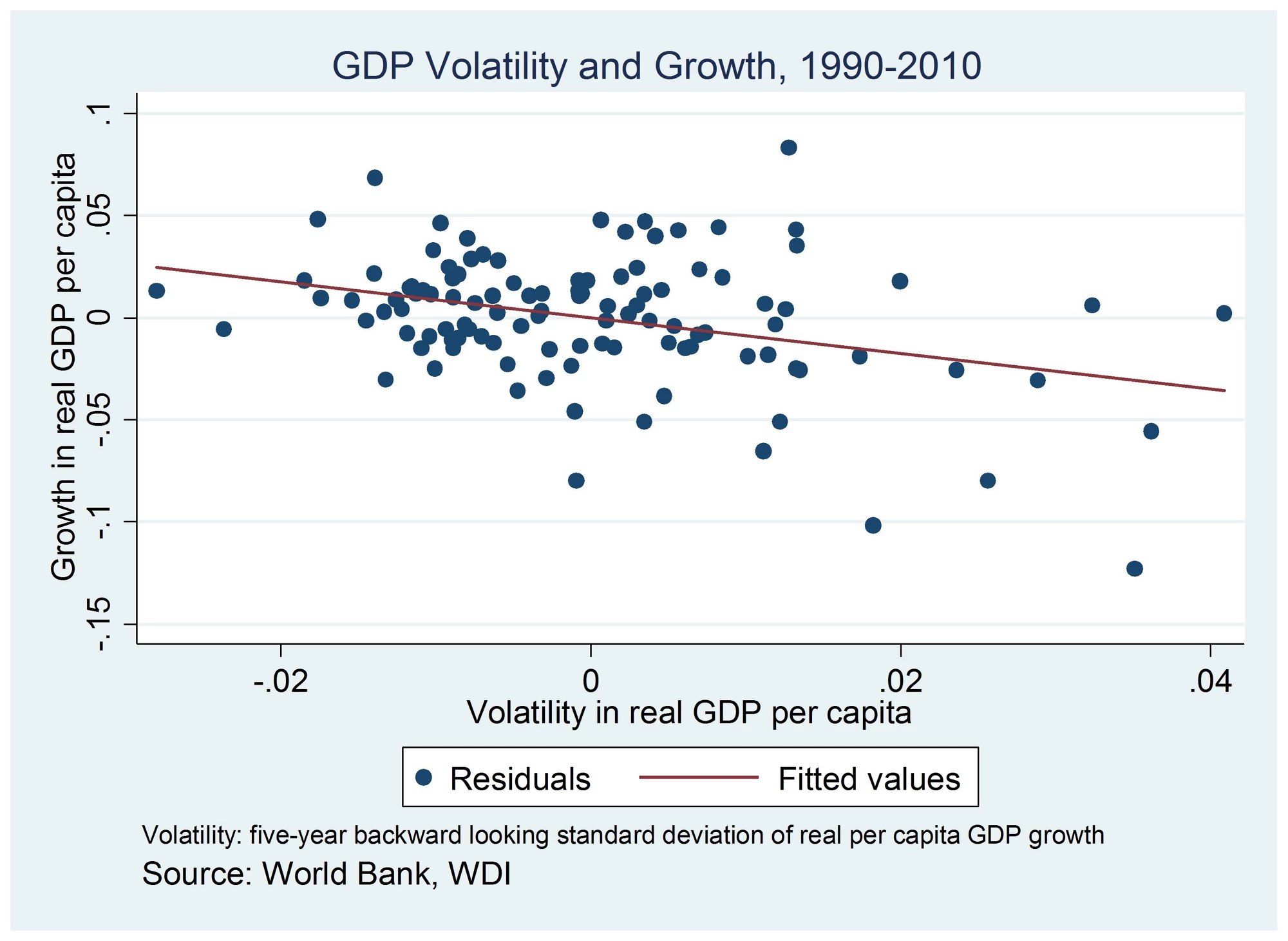

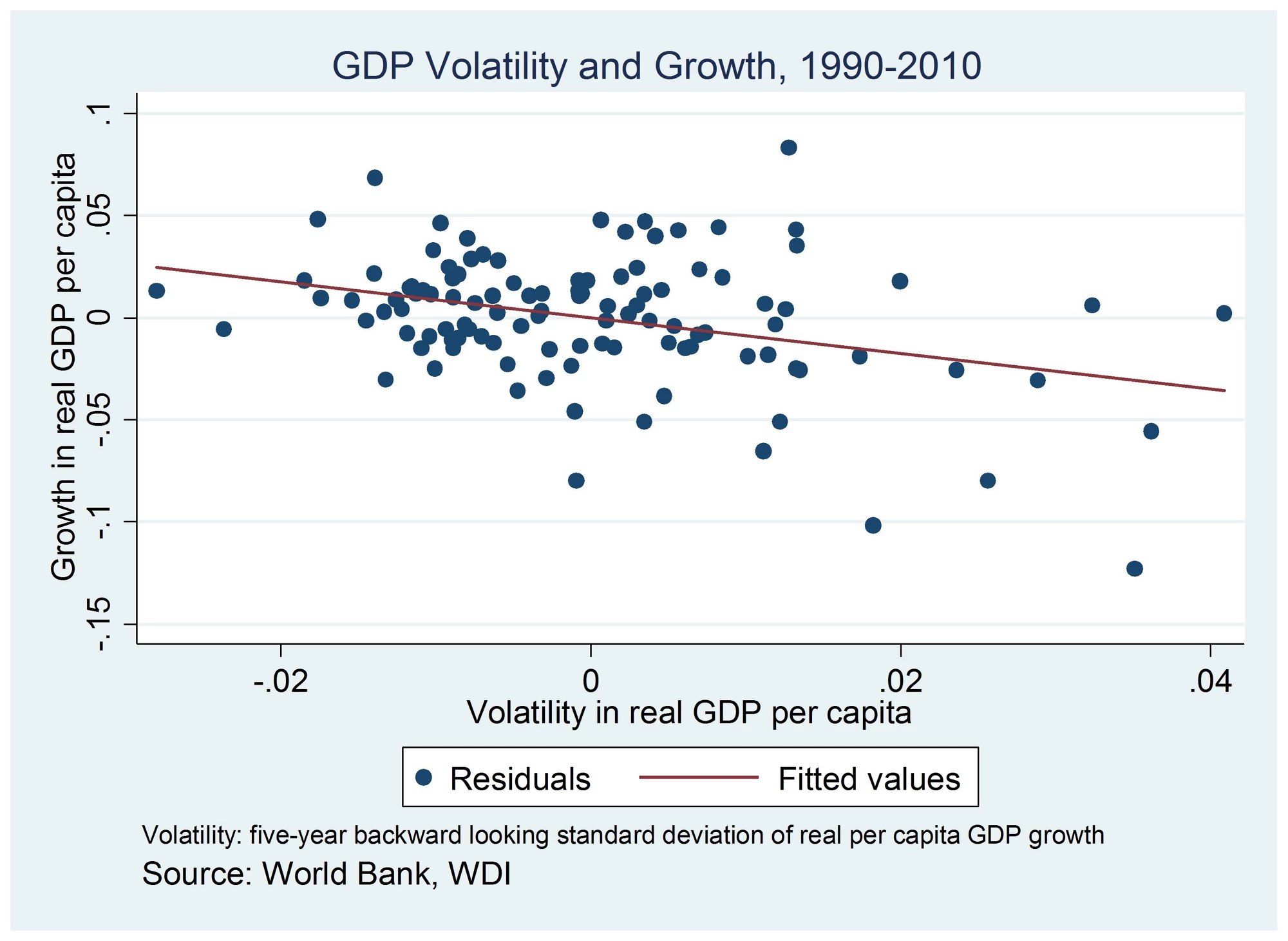

A basic conclusion—valid across the world—is that higher macroeconomic volatility means lower GDP growth. Many works in the economic literature bear this out. For instance, a 2004 study by Loayza and Hnatkovska found a direct statistical correlation, using the analytical tool known as standard deviation: A one standard deviation increase in macroeconomic volatility (measured as standard deviation of output gap) leads to a 1.28 percent average loss in annual per capita GDP growth, the authors found.

You can see the trend in the chart below as well. The horizontal “X” axis shows volatility, the vertical “Y” axis reflects real GDP growth per capita. The data points, reflecting the performance of the world’s countries, boil down to a steadily declining line in which greater volatility corresponds with lower growth.

We can also say that volatility’s danger is greater in countries whose financial systems are less developed and where governments rein in spending in hard times (the so-called pro-cyclical approach) rather than ramping it up (the counter-cyclical approach). We’ll explore that subject in more detail in later posts.

There are also many kinds of macro volatility, each one doing its own special kind of harm. Loayza and Hnatkovska, for instance, found that a recession may become deeper if the country’s government tightens credit. This leads to lower consumption and lower investment, and a tougher slog back to prosperity.

Athanasoulis and van Wincoop note in a 2000 study that because developing countries have few social protection mechanisms such as unemployment insurance, a recession is likely to make overall consumption patterns volatile. The forces build on each other: lower consumption reduces economic growth, lowering future consumption.

Volatility’s impact is especially sharp in the small Caribbean states, due to factors like these, but also because these countries lack scale and economic diversity, depending heavily on tourism or the export of particular commodities. When foreign trade proves volatile, the impact on a small island economy can be enormous.

There are three key questions to analyze: how do these forces interact, what is their effect on overall growth, and what policies are best to follow? All this is of more than academic interest: macroeconomic volatility can bring substantial hardships to millions of people

In this blog post and others to follow, we’ll offer some answers, with a focus on the small island nations of the eastern Caribbean.

A basic conclusion—valid across the world—is that higher macroeconomic volatility means lower GDP growth. Many works in the economic literature bear this out. For instance, a 2004 study by Loayza and Hnatkovska found a direct statistical correlation, using the analytical tool known as standard deviation: A one standard deviation increase in macroeconomic volatility (measured as standard deviation of output gap) leads to a 1.28 percent average loss in annual per capita GDP growth, the authors found.

You can see the trend in the chart below as well. The horizontal “X” axis shows volatility, the vertical “Y” axis reflects real GDP growth per capita. The data points, reflecting the performance of the world’s countries, boil down to a steadily declining line in which greater volatility corresponds with lower growth.

We can also say that volatility’s danger is greater in countries whose financial systems are less developed and where governments rein in spending in hard times (the so-called pro-cyclical approach) rather than ramping it up (the counter-cyclical approach). We’ll explore that subject in more detail in later posts.

There are also many kinds of macro volatility, each one doing its own special kind of harm. Loayza and Hnatkovska, for instance, found that a recession may become deeper if the country’s government tightens credit. This leads to lower consumption and lower investment, and a tougher slog back to prosperity.

Athanasoulis and van Wincoop note in a 2000 study that because developing countries have few social protection mechanisms such as unemployment insurance, a recession is likely to make overall consumption patterns volatile. The forces build on each other: lower consumption reduces economic growth, lowering future consumption.

Volatility’s impact is especially sharp in the small Caribbean states, due to factors like these, but also because these countries lack scale and economic diversity, depending heavily on tourism or the export of particular commodities. When foreign trade proves volatile, the impact on a small island economy can be enormous.

Join the Conversation