Co-Authors: Aleksandra Iwulska, Javier Eduardo Báez and Alan Fuchs

In April this year the Dominican Republic borrowed 1.25 billion US dollars on international markets in 30-year bonds. The DR is the only country in the B investment rating group that successfully issued 30-year bonds in the last 6 years. The country has a total of 2.75 billion US dollars for three issuances in the past 15 months.

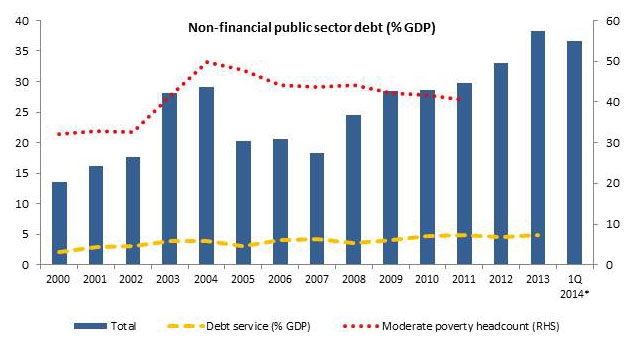

At the same time, debt levels have been growing in the country: non-financial sector public (NFPS) debt doubled from 18.3 percent of GDP in 2007 to 36.6 in the first quarter of 2014.When considering the DR Central Bank debt stock, levels would be already close to 47 percent of GDP. It is worth noticing that Jiménez and Ovalle (2011) estimated in 56.7% the debt to GDP the maximum debt to GDP threshold that investors would consider sustainable for the DR in 2013. Meanwhile, interest payments reached a peak of 2.4 percent of GDP in 2012-13 and external debt stood at 25 percent of GDP in 2013, levels not seen since the economic crisis of 2003. But the economic realities in the DR now are much different than they were in 2003. GDP grew by 4.1 percent last year and 5.5 percent in the first quarter of 2014. The Central Bank forecasts the annual economic growth at 4.5 percent this year. Meanwhile, central government fiscal deficit dwindled from 6.6 percent of GDP in 2012 to 2.9 percent in 2013.

A country with one of the highest economic growth rates in the region in the last decade, the Dominican Republic faces one important challenge: to balance a higher level of indebtedness with its high poverty rates (40 percent) and its weak equity conditions. In addition to limited poverty reduction, people have had little opportunity to escalate socially and economically to reach the middle class, with just under 2 percent of the population in the DR experiencing upward socioeconomic mobility, in contrast to 41 percent in the LAC Region. Whereas the country has succeeded in recent years in providing greater access to a spectrum of basic services, there is still high persistence of people that are not only poor in monetary sense but also deprived of the basic goods and services to enjoy fully productive lives.

Debt, growth and equity

* For Q1 2014 data reflects actual debt incurred in the first quarter of 2014 to projected GDP for 2014.

Undoubtedly, high levels of debt can slow down growth (Reinhardt and Rogoff, 2010) and transfer the financial burden to future generations. In countries with limited revenue generation capacity, growing interest and principal payments may squeeze government’s budget and crowd out other expenditures much needed by the poor. At the same time, countries with limited resources may borrow now to invest in physical and human capital (by investing in roads, schools, health centers, etc.), in a context of institutional and governance strengthening, expecting to improve equity conditions and the foundations for robust, sustainable and inclusive growth in the future.

In sum, it is difficult to predict the net effects of the current increase in debt in DR on poverty and inequality. At the same time, it is worth ensuring that debt levels are on a sustainable trend, since high debt levels could hamper growth, increase macroeconomic volatility and, ultimately, provoke a fiscal crisis, which in turn would negatively affect the poor.

Join the Conversation