كل أسبوع، يقصد الرعاة من البلدان المجاورة، خاصة موريتانيا ومالي، سوق الماشية في لينغير بالسنغال لبيع ماشيتهم. وتختلف الحالة الجسمانية للحيوانات بدرجة كبيرة حسب الفترة من السنة. فنسنت تريمو/البنك الدولي

كل أسبوع، يقصد الرعاة من البلدان المجاورة، خاصة موريتانيا ومالي، سوق الماشية في لينغير بالسنغال لبيع ماشيتهم. وتختلف الحالة الجسمانية للحيوانات بدرجة كبيرة حسب الفترة من السنة. فنسنت تريمو/البنك الدولي

For almost a year now—before the COVID-19 pandemic forced us all to stay put—I have been traveling in the Sahelian countries and talking to the many people involved in livestock production. This has enabled me to take stock of recent demographic trends. Over the last 30 years, West Africa has seen its population double and has experienced particularly rapid urbanization.

While this population growth is an asset in many respects, it also poses challenges, particularly in terms of food security. By 2050, demand for meat and dairy products in Sub-Saharan Africa is expected to increase by 327% and 270%, respectively, while demand for grains is projected to rise by 190%, in comparison with 2012 levels. In Burkina Faso, for example, milk consumption is expected to reach 1.3 million metric tons and beef consumption 0.5 million metric tons, an increase of 176% and 290%, respectively, from 2015 to 2050. This raises several questions: Can local production keep pace with the pace and evolution of demand? How can overdependence on imported livestock products be avoided? How to ensure that local animal products remain accessible to a population that is still predominantly poor and malnourished? And how to ensure that this growth is not detrimental to the environment?

We need more research and precise data to improve our knowledge of the different livestock systems and their respective costs, benefits, and limitations. But in the Sahel, it has been widely demonstrated that the pastoral system offers economic, environmental, and social benefits. Nevertheless, many misconceptions persist, and these should be cleared up.

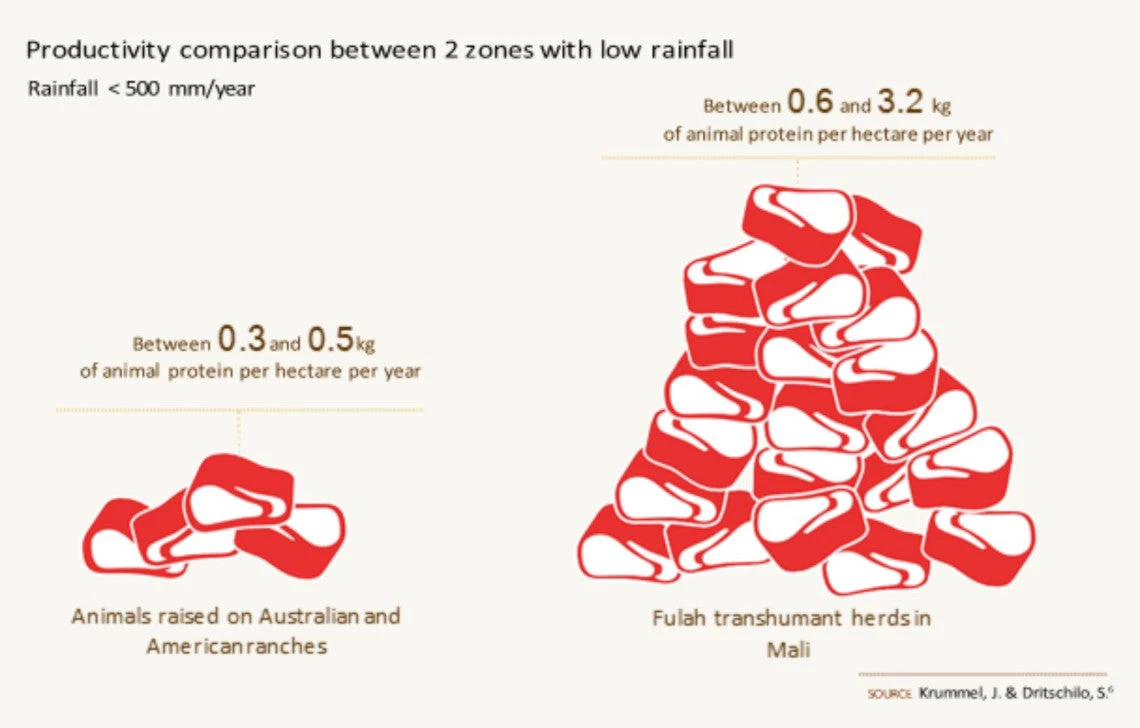

One such misconception concerns the issue of productivity. Contrary to what many may think, it has been proven time and time again that mobile livestock is far more productive than sedentary livestock in semi-arid and arid environments. Moreover, the pastoral system yields much more than meat: it provides milk, fertilizes poor soils, and allows land that is unsuitable for any other agricultural activity to be settled and put to productive use.

Contrary to what many believe, mobile livestock farming is more productive than sedentary livestock farming in West Africa. And the more mobile it is, the more productive it is! The productivity per hectare of mobile systems is even higher than that of ranching in the United States or Australia. Source: Krummel, J. and Dritschillo, S. Resource Cost of animal protein production.

That’s good news. The Sahel is home to more than 20 million pastoralists who raise nearly 60 million cattle and 180 million sheep and goats, providing much of the meat and dairy products consumed in the region and bringing income to more than 80 million people.

For a large segment of the population, pastoral products are also more competitive and affordable than products from intensive livestock production, which have higher production costs and require more inputs (feed, veterinary drugs) that are reflected in the price. Pastoral animals are also slaughtered according to demand, thus reducing the risk of losses due to the scarcity and high cost of refrigerators and cold stores. In countries with a Global Hunger Index ranking ranging from 67th (Senegal) to 115th (Chad) out of 117, the importance of having direct access to fresh milk—a food rich in essential nutrients for the millions of pastoralist and agropastoralist families in the Sahel and for the remote rural populations to whom surplus production is sold—cannot be overstated.

Pastoral products, especially fresh milk rich in essential nutrients, are more affordable for a large segment of the population than products from intensive livestock production ©Vincent Tremeau, World Bank

While people often point the finger at ruminant farming for its carbon impact, there is still little evidence to differentiate these impacts by type of production system. However, a recent study conducted in Senegal, which looked at pastoral land use as a whole, showed that pastoral systems can be carbon neutral. A broader study covering all the Sahelian countries is under way. This research, funded by the European Union, will provide really useful information that will enable us to better take these environmental factors into account in livestock development strategies.

In the meantime, it is essential to preserve pastoral husbandry in order to safeguard the livelihoods and health of millions of people. However, it will not have escaped anyone’s notice that in recent years the Sahel has been confronted with growing challenges that have made pastoral families more vulnerable. Growing insecurity, more frequent movement restrictions, and even border closures—especially with COVID19—have directly affected the mobility of animals and people. The consequences are manifold: large concentrations of animals at the borders, leading to overexploitation and degradation of resources, animal weight loss, outbreaks of animal diseases, and conflicts between herders and farmers. The closure of markets has led to a direct loss of income. If these situations were to continue or be repeated, they could seriously endanger the future of pastoralism.

Created following the adoption of the Nouakchott Declaration on Pastoralism in 2013 by Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Senegal, the Regional Pastoralism Support Project in the Sahel (PRAPS) aims to jointly address these constraints that extend beyond national borders.

A member of a pastoral family, Ainata Ka waters her goats at the camp where the family have temporarily settled while their animals graze. Doly Ranch, Thabouly Village, Linguere Region, Senegal © Vincent Tremeau, World Bank

Let’s take animal health, for example. Maintaining healthy animals is, of course, necessary for both production and productivity, yet losses due to animal diseases remain very high in most low- and middle-income countries. The presence of contagious diseases can decimate unprotected herds. Ensuring animal health is also essential to be able to access international markets. As with human health, the prevention and control of animal diseases require effective animal health systems that meet international standards. PRAPS has therefore focused on strengthening the performance of veterinary services and controlling two major diseases: contagious bovine pleuropneumonia, for which vaccination is mandatory to be able to move cattle within the ECOWAS area, and peste des petits ruminants (French for “small ruminant plague”), for which a global eradication target of 2030 has been set. The Project has supported the implementation of good vaccination practices, including technical specifications for vaccine procurement, post-vaccination serological surveys, systematic quality control of vaccine batches, awareness raising among farmers, training of field veterinary officers, maintenance of the cold chain, and vaccine administration and subsequent marking of the animal. The Project has also helped upgrade infrastructure and equipment, particularly at veterinary units along transhumance routes and at border posts. It has also modernized and harmonized the databases of veterinary services, enabling rapid feedback from the field thanks to data collection software and tablet computers made available to field agents.

As of August 30, 2020, PRAPS had financed the training of 51 young veterinarians, the construction/rehabilitation of 295 vaccination pens and 66 veterinary units, and the vaccination of more than 211 million animals. Here, a veterinarian supported by PRAPS vaccinates Ali's animals before he takes them out to graze. Niassanté Pampinabé, Senegal. ©Vincent Tremeau, World Bank.

After years of chronic underinvestment in the livestock sector, especially the pastoral sector, there is still a lot of work to do. But by putting pastoralism back on the development agenda as a priority, PRAPS has provided new impetus and opened up a path that other partners have followed. This is a very good start, but we must continue working in order to restore pastoralism to its rightful place in Sahelian policies and strategies—and in order to feed the more than 700 million people who will live in West Africa by 2050.

Join the Conversation