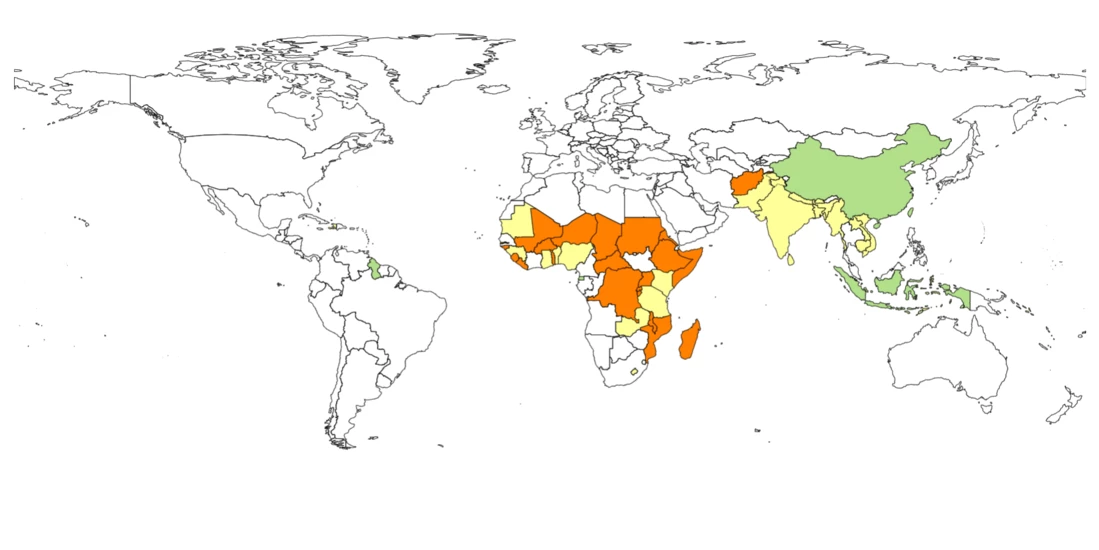

With the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), world leaders made a bold pledge in 2015 to leave no one behind on the path of development by 2030. Half-way to the target date, some 22 countries historically of low-income status are still being left behind. These countries were in a larger group of 51 countries of low-income status toward the end of the 1980s. Unfortunately, after more than three decades, these 22 countries are still of low-income status today (see Table 1).

Graduating from a low-income to a lower-middle-income status is arguably one of the first strides of development, so it is concerning that these 22 low-income countries are still unable to leap over the lowest bar. How different are they from the other low-income countries that escaped (narrowly)? What factors might explain their outcome of persistent low-income status? This blog tries to answer these deep questions.

Table 1: What has happened to low-income countries since 1987?

The starting point of this blog is the set of 51 countries that were low-income in 1987. It is encouraging that more than half (29 countries) have escaped low-income status in just one generation or so, suggesting that poverty is not destiny. While we focus on these movements across income thresholds, it is important to note that small changes in income levels can lead to moving up or down an income category, implying that setbacks are possible.

For example, Sudan graduated into lower-middle-income status in 2007 but fell back to low-income category in 2019. Moreover, there are countries that are currently of low-income status, but were not in the late 1980s (e.g., North Korea, South Sudan, Syria, and Yemen). In these four countries, there is a common thread of political instability and conflict, which might explain their current decline into low-income status (more on this later).

The 22 countries that are still having low-income status were initially poorer than the low-income countries that eventually escaped low-income status (see Figure 1, panels A and B). Their poverty rate in 1987 averaged 63 percent, which is more than 10 percentage points higher than their peers that are now lower-middle-income countries (Figure 1, panel A). One explanation for their lack of graduation from low-income status is thus partly mechanical: they started out further away from the threshold, so they had further to climb. However, this is not the full story: The countries that have always been of low-income status have also seen much lower growth rates, controlling for initial level of income (Figure 1, panel C). In fact, the 22 low-income countries were having worsening poverty rates in the early 1990s, while their peers were making progress against poverty (Figure 1, panel A).

Figure 1: Poverty and income levels

In all three groups of low-income countries, poverty has been generally falling over time, which might suggest that the 22 low-income countries are also making some progress, albeit slowly. However, it conceals the more serious point that the 22 low-income countries are being left behind. Figure 1, panel B shows that GDP per capita has been stagnant for three decades in low-income countries that could not escape low-income status, while GDP per capita has been growing in the rest of the world.

The 22 countries that have remained low-income have seen their share of the global extreme poor increase almost four-fold to 32 percent (Figure 2). About a third of the world’s extreme poor disproportionately reside in 22 out of 218 countries, accounting for 7 percent of the world’s population. The countries that escaped low-income to lower-middle-income status have also had a growing share of the world’s extreme poor but to a lesser degree from 38 percent to 47 percent. The five countries that moved from low-income to upper-middle- or high-income status have seen tremendous progress: While they still account for around a fifth of the world’s population, their contribution to world poverty declined from almost half to less then 3 percent. An important driver of that has been China, where extreme poverty declined substantially from 72 percent in 1990 to 0.11 percent in 2020.

Figure 2: Share of global poor

The 22 countries that are still of low-income status today also fare worse than those that escaped low-income status in terms of non-monetary poverty. Table 2 shows that a little over half of adults in the poorest countries are literate, compared to three-quarters in the group that has escaped to lower-middle-income status. More than 60 percent of the populations in the 22 low-income countries do not have access to electricity, and more than 80 percent do not have access to improved sanitation. A child born in any of the 22 low-income countries is will likely live up to 61.8 years, almost five years less than in the group that escaped to lower-middle-income status.

Table 2: Differences between low and lower middle income countries

So, why are the poorest countries being left behind? What factors might explain the incidence of poverty in low- and lower-middle-income countries more generally? And what could be done about it?

One question is whether these countries are in a poverty trap. This means that they are facing unfavorable circumstances outside of their control that perpetuate their poverty status. According to Jeffrey Sachs, they are poor because they are poor. In a sense, poverty begets poverty. These unfavorable circumstances may include a combination of different factors, such as being landlocked, political history, political instability, or even poverty itself. If left on their own, they have little or no hope of escaping poverty.

In Table 2, we attempt to unpack some of the possible risk factors of poverty by comparing these two groups of countries across a range of initial conditions. The results suggest that the lack of good governance, political instability, being landlocked, and belonging to Sub-Saharan Africa correlate with the inability of countries to escape low-income status. However, a country’s population size or the initial level of inequality does not correlate with remaining a low-income country.

In this blog, we have argued that we need to pay special attention to those countries that have been left behind. Twenty-two countries, home to 7 percent of the world’s population, have not managed to escape low-income status in more than three decades. Their GDP per capita has grown at a meager 0.26 percent annually since the late 1980s. These countries account for a third of the global extreme poor and their share is growing. These countries have a lot to learn from the experiences of those countries that escaped low-income status. However, we have also presented some evidence that these countries seem stuck in a vicious cycle of poverty as a result of complex factors, some of which appear to be outside of their control. This means that there will be a need for concerted engagement and support from development partners (e.g., through International Development Association (IDA) concessional financing). Otherwise, the poorest countries will struggle to eradicate poverty and the overarching goal of the SDGs to leave no one behind will not be realized.

Would you like to be updated with the latest news from the PIP team? Register to our newsletter here.

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the UK Government through the Data and Evidence for Tackling Extreme Poverty (DEEP) Research Program.

Join the Conversation