White goods are big business, and it's easy to see why. They're among the most important products for any person who cooks and does laundry, making life easier across a wide range of household functions. Therefore, it is unsurprising that as a manufactured product category – that includes refrigerators and freezers, dishwashing machines, washing (and drying) machines, and stoves – global exports hit almost $90 billion in 2015.

Some countries that will leap to mind when thinking about white goods – because of the prominent consumer brands that emanate from them – are Germany (with such household names as Bosch or Miele) and the United States (Whirlpool). As with all manufactured goods, China is also a big exporter. However, among the world’s top exporters for home appliances is a county that not everyone would immediately guess: Turkey.

Turkey is in the top ten global exporters of fridges and freezers, washing machines and stoves, only just missing the top ten for dishwashers – but with growth averaging 15 percent a year over the past ten years, it's only a matter of a few years before Turkey is among the top-ranked exporters for this product too.

Growing steadily, then going global

Among Turkey’s better-known white-goods manufacturers is the firm Arçelik, a part of the industrial conglomerate Koç Holdings. Founded in 1955, Arçelik started off making office and metal furniture, producing its first washing machine in 1959, its first refrigerator in 1960, and launching a vacuum cleaner plant in 1979 and a dishwasher plant in 1993.

However, among the firm’s various accomplishments, one stands out, both to outside observers and for the company itself: when Arçelik broke out of Turkey to go global, first in the markets Arçelik sold to and then in its production locations.

This expansion has occurred both through organic growth and through strategic acquisitions. For example, aside from the Arçelik brand itself, among the firm’s flagship brands is Beko, initially a home-grown brand that in the 1990s was assigned to drive Arçelik’s expansion outside of Turkey. The Beko team was tasked with the goal of “being a world brand”: Today a Beko-branded product is sold, worldwide, every two seconds.

To further the global foothold gained by Beko, in 2007 Arçelik made a flagship acquisition of Grundig, one of Germany’s foremost home appliance and electronics brands. Today, more than 60 percent of Arçelik’s sales are made outside of Turkey through sales and marketing offices in over 20 countries, with its brands selling in moere than 130 countries worldwide.

Accompanying this market penetration has been a widening production footprint, with Arçelik running 18 different production facilities across Turkey, Romania, Russia, China, South Africa and Thailand. However, this success of its expansion strategy has not come without its challenges. Differences in business processes – and business culture – when integrating new manufacturing facilities into the group have tested the resilience of the firm’s staff, as has aligning the brands in terms of design and marketing activities.

Owning property

The first manufacturing venture of the Koç Group started in 1940, when it began the manufacture of lightbulbs in partnership with General Electric. Building on this experience, most of the Koç Group’s entry into new products has been in partnership with international firms, allowing it to be among "Turkey’s firsts" in the manufacture of many products, from white goods to automobiles. This has applied to Arçelik, too, which started off manufacturing washing machines and refrigerators under license from different companies.

However, as Arçelik deepened its manufacturing experience, it also began to increase its independence from its international partners, launching an internal research and development (R&D) team in 1991 to drive product development and innovation. By 1997, Arçelik ended all licensing from other companies. Today, Arçelik’s has more than 2,000 patent applications and accounts for one-third of Turkey’s international patent applications to the World Intellectual Property Organization.

Its R&D is driven by a balance between "doing the right R&D" (picking the right technology) and "doing R&D right" (effectively managing the process from prototyping to mass production). This requires a careful balancing act between the effort dedicated to research and the effort dedicated to production deployment: If there is too much focus on the former, the team risks turning into an academic research laboratory; if there is too much focus on the latter, the team risks turning into a product-development unit without enough of an innovative edge.

To maintain this innovation success, Arçelik is actively investing in its R&D infrastructure, with 14 R&D centers in Turkey, a new center at the Cambridge University Science Park in the UK, and a hub in Taiwan. Two new R&D centers are planned for Germany and the United States, ensuring proximity between product development and key end-markets.

Emulating Arcelik

Arçelik stands out as an impressive example of growth and transformation for anyone directly involved in business or supporting the growth of businesses. It is particularly inspiring because it is an example of a firm from an emerging-market country that has successfully gone global – and truly global – expanding into advanced-economy markets. It is also inspiring because it is an example of a firm that has managed to develop its own R&D and innovation successes, no longer dependent on imitating other firms’ products but creating its own.

This is a far cry from the contract manufacturing in which many developing- and emerging-market firms find themselves, perhaps most strikingly embodied by the text on the back of every iPhone: “Designed by Apple in California. Assembled in China.” This separation of responsibility, and the difference in value capture that it embodies (and in capabilities that it implies), is a challenge that dogs many developing- and emerging-market manufacturers, and is one that few have been able to overcome. To borrow a phrase that describes barriers to women’s advancement in the workplace: Manufacturers in developing and emerging markets face a "glass ceiling" that limits their growth, where they are unable to develop and own the brands of the products that they make (or find that their brands are restricted to domestic markets or, at most, to a few neighboring markets in their region).

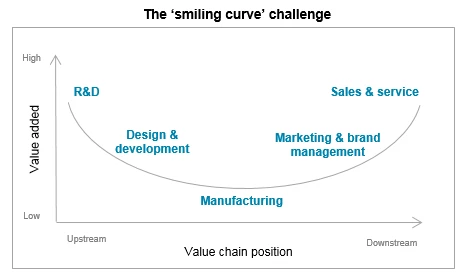

They similarly find it challenging to lead on innovation, instead manufacturing products that are designed elsewhere, either following specifications from buyers or copying products. Yet the real profits in most products reside upstream in design and product development, and downstream in branding and sales, with manufacturing and assembly taking a limited share of the profits – a challenge highlighted by the so-called "smiling curve," originally used in 1992 by Acer’s founder, Stan Shih, to illustrate the challenge that information technology manufacturers in Taiwan faced when finding themselves often at the bottom of the curve.

In light of this common experience, and the seeming limitation to growth that it embodies, Arçelik stands out as a beacon and example, showing that developing- and emerging-market manufacturers can grow to build (and acquire) their own global brands and to be positioned on the cutting edge of innovation in their industry.

Join the Conversation