World Bank

World Bank

The recent Call to action for Rural Sanitation highlights the need for increased attention to address the rural sanitation agenda. Rural areas are home to 91% of the 673 million people who continue to defecate in the open, and to 72% of the 2 billion people without basic sanitation services.[1]

Despite these high numbers, several countries have made significant progress in ending open defecation. Nepal declared itself ODF (open defecation free) on September 30, 2019. India followed suit a few days later. In Bangladesh, open defecation is practiced by less than one percent of people in rural areas.

These success stories hold an important lesson for other countries, such as Nigeria, that are about to embark on rural sanitation campaigns. The “campaign” approach has been effective in pursuit of the 2015 Millennium Development Goal – basically, to ensure that everybody has a toilet and uses it. But when that is achieved, once generous financial support and human resources tend to be withdrawn.

Achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal for rural sanitation instead requires a “service delivery” approach, as illustrated by this typical experience reported by a village headman in Rajasthan[2]: “Once we became ODF, all district officials disappeared and there was no money any more. Who is going to help us remain ODF? Who is going to help us improve our toilets?”

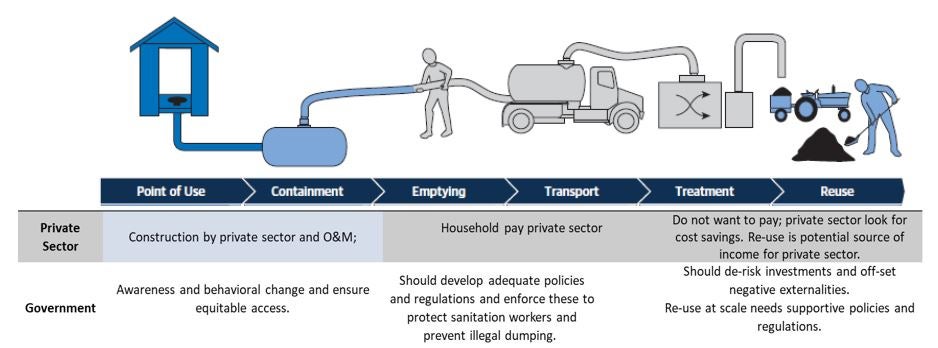

A recent World Bank report draws attention to the challenges of safely managing fecal sludge in densely populated rural areas - an issue that has received less attention than sanitation challenges in cities. The report looks at six parts of the rural sanitation service delivery chain – use of a toilet, containment of the waste, removal of the waste, transport to a treatment site, treatment, and reuse of the treated waste.

Potential market solutions exist in each of these areas. In addition to constructing latrines, in many countries, the private sector provides some emptying and transport services. Costs are then recovered by charging users and selling the waste, typically as fertilizer.

However, at each step there are negative externalities and market failures, particularly in transport and treatment. There is considerable scope to innovate business models in areas such as logistics and waste-to-resource processes, but market solutions will typically be safe and profitable only with public support and partnership arrangements. As the report concludes:

‘Public funding—whether through subsidy or market concession—will be needed to cover the affordability gap and address safely managed sanitation, requiring a clear and long-term commitment and support from government’.

The role of the public sector includes:

- Public funding—whether through subsidy or market concession. Ensuring no one is left behind by providing financial incentives for poor households if needed (see also Doing More with Less : Smarter Subsidies for Water Supply and Sanitation), or providing treatment and transport services where the private sector does not.

- Raising public awareness about operating and maintaining on-site sanitation systems, not just about constructing them.

- Enforcing regulations to ensure the health and safety of sanitation workers and citizens.

- Creating a supportive policy environment for safely managed sanitation and waste-to-resource activities – for example, by defining standards for waste-to-resource products.

- Supporting research and development.

- De-risking private sector operations through guaranteed purchase agreements of waste-to-resource outputs.

There is much to be learned about how policies, institutions, and regulations can hamper or support the development of an equitable, safe, and sustainable sanitation service chain. The leading advanced countries, such as Sweden, can offer pointers.

Lessons can also be learned from non-networked urban sanitation solutions, though there is more scope for on-site sanitation solutions in rural areas: in some contexts, a well-constructed and maintained twin-pit latrine can be an acceptable solution, as can septic tanks. Service delivery models need to be developed and tested to ensure that users are educated, technology selection is informed, and implementation is rigorously supervised.

But what is needed to provide equitable, safe, and sustainable rural sanitation services will vary from location to location. In many potential areas of opportunity – such as co-treatment of agricultural waste and fecal sludge – technologies exist but have yet to be tested at scale in relevant contexts. Innovative thinking is required to improve existing technologies and find new, low-cost solutions for particular challenges – such as areas that are flood-prone or have high groundwater tables.

Transport of waste is typically more complicated and costly in rural than urban areas due to lack of infrastructure. Only with a detailed understanding of local logistics and potential waste-to-resource markets can workable business models be developed.

Join the Conversation