Woman technician operating grinding machine during industrial training class at a government industrial training institute in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Woman technician operating grinding machine during industrial training class at a government industrial training institute in Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India.

In the decade before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, South Asia struck a strong growth note of 5 percent per year in per-capita GDP, strongly outpacing other developing regions in the world, notably Latin America and the Caribbean; the Middle East and North Africa; and Sub-Saharan Africa—all of which grew less than 1 percentage point per year. Only East-Asian economies outperformed South Asia at a growth rate of 6.5 percent.

Undoubtedly, South Asia as a region, possesses a powerful growth engine.

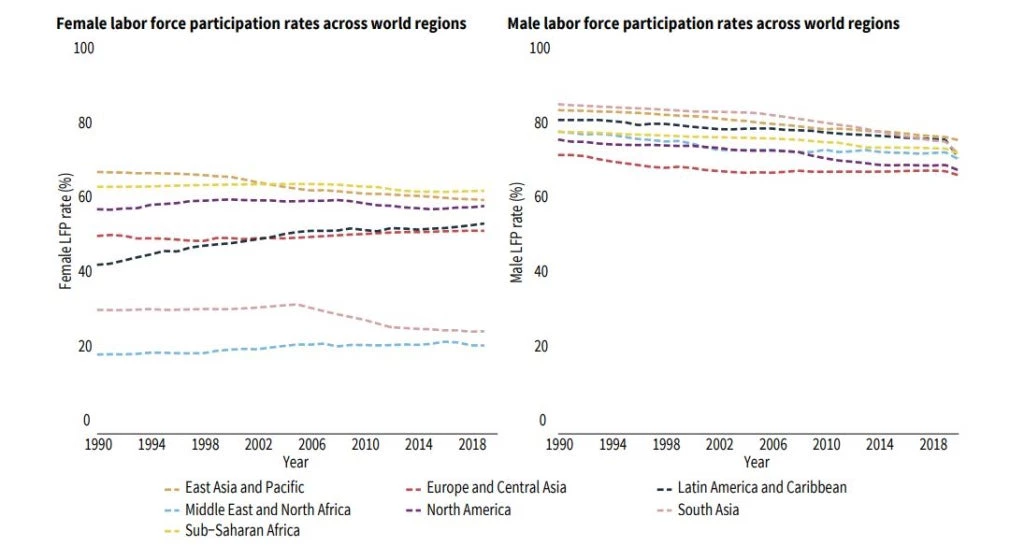

Yet, what is striking is that this engine has not been firing on all cylinders, implying that large numbers of people and significant parts of the economy are not participating in the strong growth. In South Asia, only 20 out of every hundred women actively participate in the labor market, while the labor force participation for men is 80 percent, far below the participation rates in other regions.

- Between 80-90 percent of the workforce is stuck in unproductive informal sectors that have notoriously limited access to credit and sales markets.

- The region’s exports of goods—traditionally a source of productivity growth—are only one third of the size of exports when compared to other countries around the world.

The economy’s sum is greater than its parts

From the findings above, it appears that most of South Asia’s economic activity is concentrated in small pockets of societies, namely the formal workforce and male workers mostly employed by formal firms that have access to credit and are largely selling to domestic markets. These segments can grow fast, but this is not the full throttle mode that is required to launch economies to their fullest potential. Therefore, it’s not a surprise that currently, per-capita income in South Asia is only one fifth of the per-capita income in East Asia, a region with a much larger female labor force participation, smaller informal sectors, and an export-led growth strategy.

For South Asia to reach its full economic potential, it must explore untapped opportunities.

Let’s start with low female labor force participation.

The latest South Asia Economic Focus zeroes in on a possible answer to this conundrum. Using new data from 140 countries, the chapter on gender norms shows that in South Asia, perceptions about the role of women in society have not kept up with new economic opportunities as they have done in many regions of the world. The analysis shows that these gender norms determine to a large extent, the participation of women in the labor force.

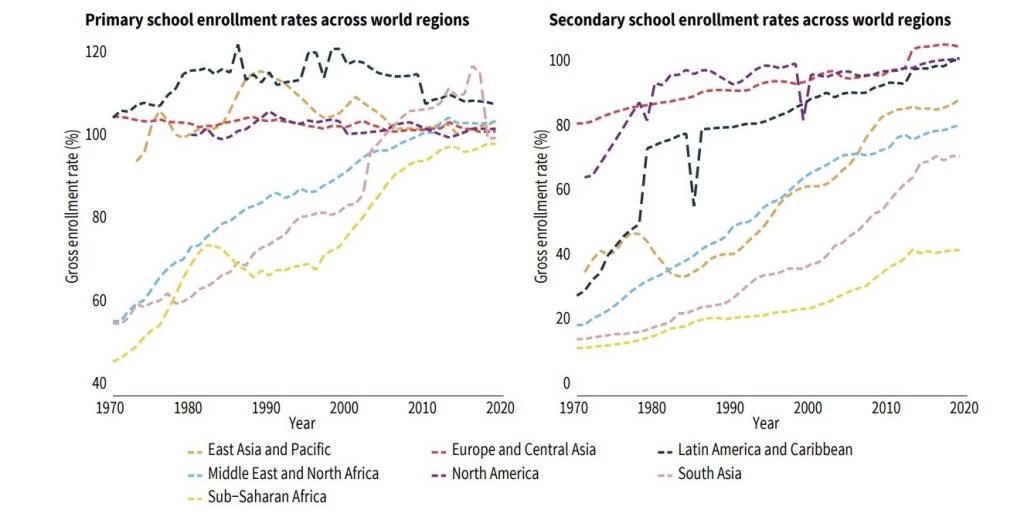

The paradox here is that in most countries, education of girls tends to increase female labor force participation as education increases potential wages, which makes it more attractive to participate in paid work. However, in South Asia, whereas education of girls has improved significantly during these past decades, the participation of women in the workforce has not kept up to speed. If norms mandate that married women stay at home, then women are likely to withdraw from the labor market after marriage, irrespective of their education level. The latest South Asia Economic Focus also shows that conservative norms in South Asia are associated with other forms of gender inequality as reflected in freedom of movement, asset ownership, access to finance, preference for the male child, and domestic violence.

Let’s examine the challenges of the informal sector.

South Asia is split between a well-connected and well-protected formal sector where only 10 percent of the workforce is employed, and an informal sector, which employs 90 percent of the workforce —a trend that has been extraordinarily persistent for decades. We know that a large informal sector (and conversely a small formal one), is detrimental to development because it limits the tax base as many informal firms remain below income tax thresholds; it keeps informal workers vulnerable due to lack of social protection; and informal firms lack legal protection to access credit, curtailing their productivity, business expansion, and overall economic growth.

However, there are strong forces that keep this informality stubbornly in place. Firms and workers in the formal sector have privileges such as high wages, easy access to credit from banks, and political connections that they can maintain when barriers to enter the formal sector remain high. In economics, measures that keep a group small to create unique benefits for them, are called insider-outsider policies. In this case, the outsiders are the workers in the informal sector. These outsiders have limited access to finance and markets and find it difficult to challenge the position of insiders. The result is a stable system, but one that unfortunately underutilizes the resources of the informal sector.

Third, we look at the lackluster growth of exports.

South Asia has a largely inward-looking development strategy with domestic firms being shielded from foreign competition, and that has created economies where exports of goods are only one third the size of exports as compared to other countries across regions. Trade protection reduces productive growth in firms, which makes it harder for them to compete in international markets.

True, South Asia has experienced periods of rapid GDP growth during the last two decades. But that was largely caused by opportunities to catch up when you start at low levels of development. South Asian countries must be relentless in removing barriers to trade so that countries can develop and grow their economies and increase overall productivity.

A time of change is a time to change

Norms prevent reality from changing, and an unchanging reality reconfirms the norms. However, a crisis can catapult much-needed change by challenging this status quo, especially when it brings home the fact that an old development model is unsustainable. We witnessed this in South Asia during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the crisis hit informal workers and women exceptionally hard. That could well be an opportunity to rethink the position of women and informal workers. In South Asia, more than 80 percent of women in non-agricultural jobs are in informal employment, and this leaves women often without any protection of labor laws, social benefits such as pension, health insurance, or paid sick leave. Concurrently, the COVID-19 crisis also boosted digital technologies, as new technologies almost always get a boost during a major crisis. These digital technologies open new opportunities for women to participate in the economies and for the informal sector to get access to finance and markets, including international markets.

There’s no better time than now for South Asia to challenge existing norms and paradigms and especially create opportunities for the less privileged: women and informal workers. Such a strategy is not only the right thing to do, but it will establish better equilibrium for growth and help economies take off full speed towards inclusion and long-term prosperity.

Join the Conversation