How to think about it

So, does paying children to read work? Well, “work” for what? Why do we want children to read books, anyway? Adichie wants them to read to “understand and question the world.” We also want children to read books to increase their reading comprehension and to learn to love reading for both enjoyment and improved opportunities in later life.

What are the potential goods and bads of paying children to read? Guryan et al. (2016) have a nice discussion. On the good side, children may lack self-control or may lack a long-term vision of the benefits of reading and so may underinvest. Providing an incentive may help them learn to read better with a higher immediate benefit (“increasing the marginal return to education related activities”). This could happen through a direct effect (“I want the incentive and so I’ll read more”) or indirectly, through parental investments (“My parent wants is reading with me to help me get the incentive”) or peer interactions (“All my friends are doing it too!”). Perhaps they’ll discover a love of reading along the way.

On the bad side, extrinsic incentives can – in some scenarios – crowd out intrinsic motivation. In other words, offering the reward might actually reduce whatever internal interest in reading the kid has. Why? Gneezy et al. (2011) give a couple of reasons: The first is that establishing the extrinsic incentive may signal something about the activity: Reading must not be fun, or they wouldn’t be paying me to do it! The second is that the incentive could reduce the value of pro-reading preferences: “I’ve always thought reading is cool, but now everyone’s doing it because of the rewards! Maybe I need a new image.” If extrinsic incentives reduce intrinsic motivation, then kids may be less motivated to read after the program ends. Another downside is that an incentive may lead to a focus on the goal (finish the book!) at the expense of the process (enjoy the book and understand the book!). Here’s an anecdote to demonstrate, drawn from Small et al. (2009):

Of course, if kids have no motivation to read before the program, then maybe we don’t need to worry about the adverse effect of incentives on them. Skimming books is arguably better than not reading them at all, and they had no intrinsic motivation to crowd out.

$2 a book in Texas, USA

Some years ago, Fryer (2011) published results on a U.S.-based program in which second-grade students received $2 per book for up to 20 books per semester. To qualify for the $2, they had to score 80 percent on an online quiz about the book (which they could take only once). They could choose books from their school library or classroom, and there were quizzes available for about 80,000 books in total. An incentive check was written to the students three times a year. (Average payout for the year was almost $14, with a maximum of $80.) Average effects on reading achievement are tiny (0.01 standard deviations) and insignificant. Students who took the achievement test in Spanish performed worse, “entirely driven by the lowest performing students.” Of course, this might be driven by the fact that most of the books available were in English, so the incentives may have crowded out effort on Spanish. When separated out, those who took the test in English show a positive, statistically significant impact, at 0.22 standard deviations. Fryer tests for self-rated intrinsic motivation and finds no significant impact.

Books in the mail in the northeastern USA

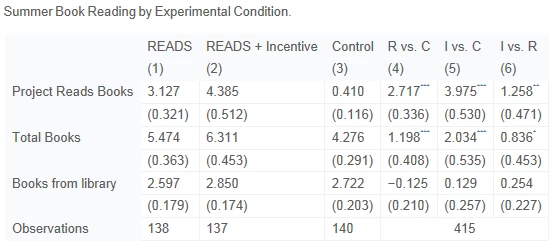

More recently, Guryan et al. (2016) [ working paper version] test incentives to read during summer break. Students going into 4 th or 5 th grade were randomly assigned to Project READS, Project READS + incentives, or a control group. Project READS kids received a book in the mail, together with a postcard: “The postcard asked them to list the title of the book they read, what their favorite part was, and asked them to check off each of the reading strategies they used when reading the book.” Who picked the books? Before the summer break, students attended a book fair and selected 14 (out of a collection of 115) books they were interested in. Implementers then selected the 10 books most closely match to students’ reading ability.

Kids in the incentives group earned 5 points per book and received a catalog of prizes they could buy, worth between 5 and 50 points: “The prizes included Captain Underpants books, art sets, board games, sports equipment, t-shirts and hats with local sports teams’ logos, magazine subscriptions, and science kits.” They received the catalog every week, together with the new book.

Control group kids received 10 books in the fall. So everyone got books! Reading motivation was measured at baseline using the Motivations for Reading Questionnaire.

As you can see in the table below, kids in the READS and the Incentive group both read more Project READS books than kids in the control group. But of course, the point isn’t really these books in particular, but rather to get them reading more books period. Control group kids read 4.3 books on average, whereas READS kids read 5.5 and Incentive kids read 6.3. All those differences are statistically significant, at least at 90 percent.

Because of a limited range in book selection, not all readers were equally well matched to the books they were sent. The biggest effects appear for those readers who were well matched to their books, with the READS kids reading 1 more total books than control and Incentive kids reading 1.7 more total books than the READS kids. The effects were smallest for kids who received books that were too hard.

Did they read better as a result of the program? No. Across a range of reading comprehension tasks, students in the treatment group did no better than students in the control group.

But wait, there’s nuance! The incentives – not the READ program by itself – actually did lead some students to better reading comprehension: the students who were more motivated to read at baseline. Likewise, there are suggestive results that the impacts on number of books read were highest for those who were motivated at baseline. So rather than motivating the unmotivated, the incentives encouraged those who would have been reading anyway.

The take away: “Rewards may not be a well-targeted strategy for increasing educational investments by less-motivated students. In addition, our findings imply that incentives could increase achievement gaps since motivation positively correlates with baseline ability.” The authors are quick to note that this is isn’t the only possible interpretation; it may be that mailing books out simply wasn’t enough, and that less motivated students needed more complementary inputs. The Fryer results also present a mixed picture, with the lowest performing students gaining the least (but that effect is confounded by language issues). Still, this evidence pushes back against the initial idea that paying students to read is a great way to get unmotivated readers into the spirit of reading.

So definitely continue to seek to inspire a love of reading among those children who haven’t caught the spark. But think twice about paying them.

Thanks to Ben Piper for pointing me to the Guryan et al. paper.

Join the Conversation