Mariano Bosch is a Senior Specialist at the Labor Markets and Social Security Unit, Inter-American Development Bank.

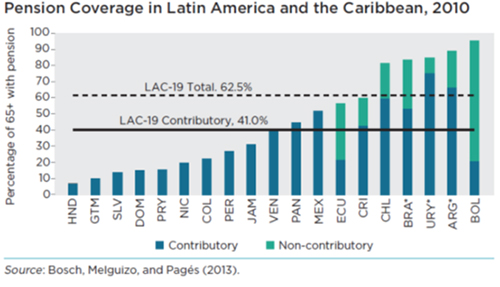

The panorama of pension coverage in Latin American and the Caribbean(LAC) is quite worrisome. Fewer than half of the 38 million older workers (aged 65 and older) are receiving a contributory pension — that is, a pension based on contributions (savings) accumulated during their active lives. Some LAC countries in recent years have managed to increase pension coverage based on non-contributory pensions (or, more correctly, a pension paid from the collection of general taxes levied on the public). However, the majority of pensions (either contributory or non-contributory) pay less than US$ 10 a day.

This bleak picture leaves only a small number of the region's elderly in a position to enjoy the two key objectives of pension systems: eliminating poverty in old age and maintaining an adequate standard of living for workers once they stop working. Moreover, without further reforms, the situation is expected to worsen. How can LAC expand coverage and better protect its workers? A new flagship report from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) — Better Pensions, Better Jobs: Towards Universal Coverage in Latin America and the Caribbean — calls for a universal non-contributory pension system, along with labor market reforms that promote more formal sector jobs. At this point, most jobs in the region are informal, meaning that firms and workers aren't contributing to social security.

The design and functioning of the social protection system

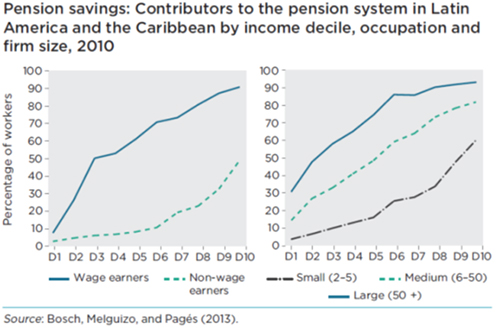

Social protection systems in LAC came into being in the 1930s and 1940s under the influence of the social insurance system implemented in Germany in the late 19th century. This scheme was created with the understanding that social benefits are for wage earners who acquire them by means of contributions paid jointly with employers. Much of the low coverage observed today stems from this original design. On average, only 4 out of 10 LAC workers are contributing to a social security system (see figure 1). Plus workers in the lower part of the income distribution, especially those self-employed or working in small firms, are largely disconnected from social security institutions (see figure 2). That said, some LAC countries in recent years have substantially increased pension coverage based on non-contributory pensions, which has boosted the proportion of older adults who receive a pension to more than 6 out of 10, even if the payout is meager.

Figure 1 Pension coverage in LAC is way too low

Figure 2 Non-wage earners and small- and medium-size firms are hardest hit

As a result, around half of the 140 million elderly in the region in 2050 won't be eligible for an adequate pension. At this point, LAC's population is young but aging rapidly. While in 2010 the percentage of older workers represented only 6.8 percent of the population, projections suggest that by 2050 this age group will grow to 19.8 percent.

A path to universal pension coverage

Going forward, policy makers need to balance two challenging objectives: (i) providing coverage for current uncovered elderly, and (ii) establishing the foundations for coverage in the future.

The first one can be achieved through an anti-poverty non-contributory pension for all citizens. It should be established with strict eligibility criteria in terms of age and at a level sufficient to reduce poverty in old age; have a stable funding source; allow for receiving both non-contributory and contributory pensions; and be supported by strong fiscal institutions.

The second one will necessitate mechanisms to promote formal employment. Among other options, subsidies can be offered to reduce contributions for wage and non-wage earners, favoring the incorporation of low- and middle-income workers into the formal system.

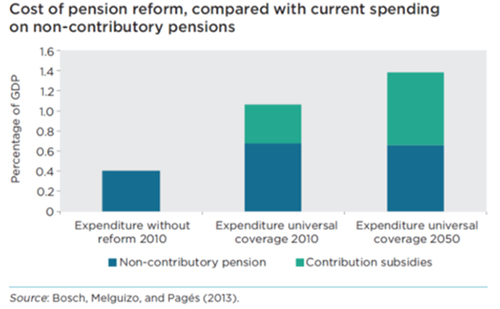

These instruments hold the potential to eliminate poverty in old age — the average poverty rate in LAC for people aged 65 or more is an average 19.3 percent — and lead to a significant and sustainable increase in formal employment and pension savings. Furthermore, subsidies for formal employees could increase formal employment. Fortunately, the cost of these combined measures will be no higher than 1.4 percent of GDP (see figure 3) — about one percentage point of GDP per year more than the amount that the region is already allocating to non-contributory pensions.

Figure 3 The price tag of universal pension coverage and measures to stimulate formal work

In all, Better Pensions, Better Jobs concludes that it is possible to move toward universal coverage in pensions, and that under certain conditions, the system is affordable now and in the future. However, achieving this goal requires not only establishing sustainable and efficient anti-poverty pensions but also making a firm commitment to create more formal jobs for the people that are in the labor market today. In fact, the report argues that this is the only sustainable strategy for providing adequate pensions in the long term. Informality is not an incurable disease from which the region inevitably suffers. It is the outcome of the original designs of social welfare systems, the incentives provided by the state in labor markets, and the value placed by workers and firms on the benefits of formality. All this can be changed. But to do so, we must understand what restrictions are preventing the creation of formal employment and implement the policies needed to remove those restrictions.

This post was first published on the Jobs Knowledge Platform.

Join the Conversation