An automotive training center in Hawassa City facilitates the participation of female youths from disadvantaged backgrounds in the urban safety net's Youth Apprenticeship Program. Photo: Emiliano Ruprah/ World Bank

An automotive training center in Hawassa City facilitates the participation of female youths from disadvantaged backgrounds in the urban safety net's Youth Apprenticeship Program. Photo: Emiliano Ruprah/ World Bank

Sub-Saharan Africa has the world’s fastest-growing workforce, increasing by as many as 12 million youth every year. We need to redouble our efforts to help these young people as they enter the job market.

Yet, while African economies have increased fivefold since 2000, this growth has failed to deliver broad job creation. Only one in six workers in Sub-Saharan Africa gets a regular paycheck, compared to one in two workers in high-income countries.

The world risks missing out on this generation’s potential. Most youth are underemployed in unstable, low-paying, and low-skilled jobs, a challenge compounded by crises such as economic slowdown, climate stress, and conflict.

How can we change this?

New research is helping us learn what we can do for today’s workforce. Reforms that help African economies create more and better jobs over the long-term are important. But we also need to start by meeting young people, and other disadvantaged workers, with support that matches their immediate needs and reality.

Ethiopia illustrates a practical way to reach poor workers. Layering complementary services — like financing, training and coaching, and networking — through existing government social safety net systems can help people earn more by diversifying into self-employment and connecting to existing wage jobs.

Below, I highlight some of the key pieces of the country’s efforts, and you can delve into these even further in a new book, Working Today for a Better Tomorrow in Ethiopia: Jobs for Poor and Vulnerable Households.

The Ethiopian labor market: persistent challenges, new crises

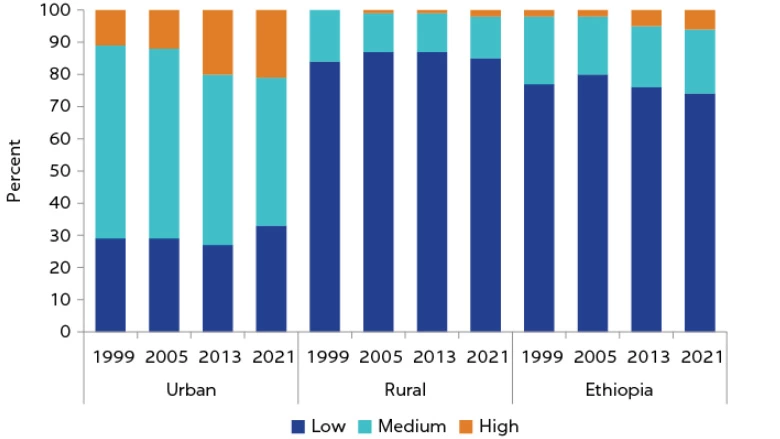

When we look at jobs in Ethiopia, the pattern is striking. About three-quarters of workers are in low-skilled jobs, not a major shift since 1999. Most people continue to work in agriculture as self-employed or unpaid family workers.

This low-skill, low-productivity work has a direct impact on people’s well-being. Despite GDP growth of almost 40% in the last two decades, rural incomes have grown by only 6%, and poor rural households saw no increase at all.

Ethiopia has seen little shifts away from low-skilled employment

Skill composition of employment, nationally and by location, 1999-2021

Source: World Bank calculations using data from the ELFS, 1999-2021

Source: World Bank calculations using data from the ELFS, 1999-2021

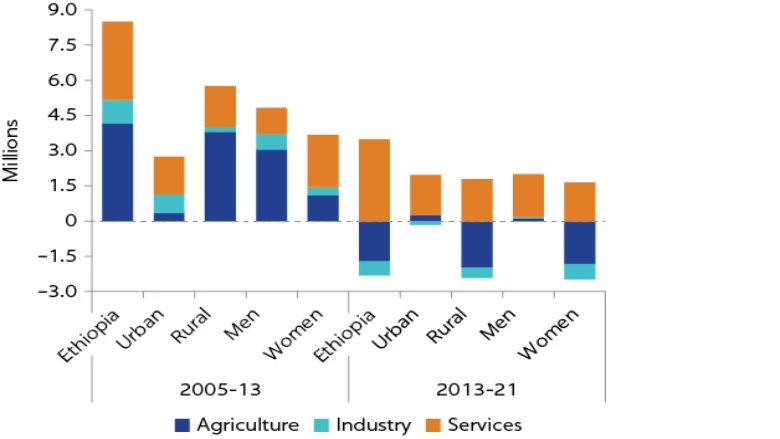

As in many countries, we see that the service sector is one area of new job creation. Global research shows that services are gaining increased importance in transforming economies.

Unfortunately, the scale does not match the need. In the previous decade, we saw about 3 million jobs added in the service sector. In the coming two decades, we expect around 20 million young people to enter the labor market.

The service sector has driven job growth in Ethiopia over the last decade

Source: World Bank calculations using data from the ELFS, 2005-2021

Source: World Bank calculations using data from the ELFS, 2005-2021

Barriers to good jobs: Meeting people to overcome their unique challenges

But it’s not just about the job market. People come looking for jobs with very different backgrounds, expectations, and access. We need policies that reflect these different realities.

The job experiences of four vulnerable groups — which together make up about half of the Ethiopian population — underscore the urgency to act now.

1) Urban youth: Ethiopia’s largest generation faces rising unemployment, and most urban youth work in low-skilled domestic jobs. More than 70% of youth have only a primary education, leaving them out of high-skilled service jobs such as finance, ICT, and scientific fields that grew the most in recent years.

2) Rural-urban migrants: Only six% of adult Ethiopians moved from rural to urban areas between 2016 and 2021. Increasing migration, particularly to towns and small cities, could promote better job opportunities, particularly for poor people.

3) Rural women: Working women earn only 73% as much as men. In rural Ethiopia, women face greater time and education constraints than men, but our analysis showed that a lack of productive inputs, such as access to land or financial services, is the main driver of the gender difference in earnings.

4) People with disabilities: Limited data on people with disabilities indicate that they are poorer, less educated, and less likely employed. Without better evidence, we cannot understand how to support people with disabilities in Ethiopia.

Social safety nets can bridge limited opportunities today and growth tomorrow

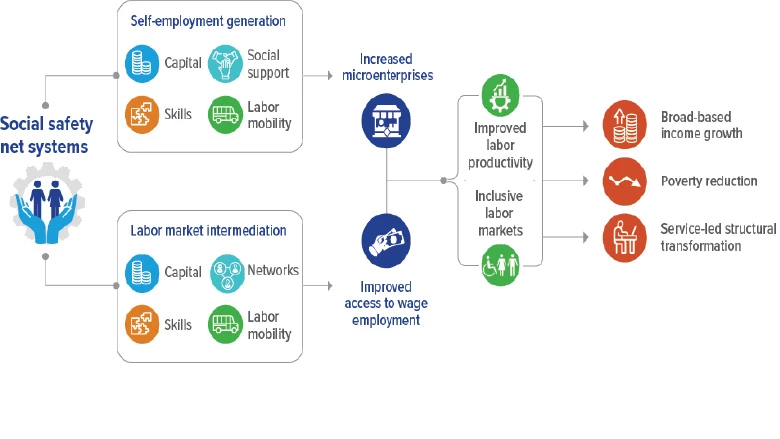

Ethiopia’s social safety nets already help many of the country’s extremely poor to improve their well-being. Ethiopia can leverage these same programs to help improve their job opportunities too.

Global evidence suggests that safety nets help people create their own jobs and diversify how they earn a living. A pilot self-employment program saw participating Ethiopian households increase consumption by almost 20%. While we are still learning how best to scale up this type of support through government systems raises, this effort is one way to build on safety nets and provide people with targeted and tailored support to start microenterprises.

Safety nets also can serve as a tool that connects poor people with existing jobs. While out of reach for most Ethiopians, there are employers looking for wage workers in Ethiopia’s towns and cities. Social safety nets can provide support such as apprenticeships, training, networking, and transport subsidies that prepares them for and links them to this type of work.

Scaling up and building on social safety nets can help transform the lives of young Ethiopians and other vulnerable people. This is one practical example showing how a country can invest in today’s workforce to build tomorrow’s inclusive economy.

Improving Labor Outcomes for Poor and Vulnerable Workers in Ethiopia

Join the Conversation