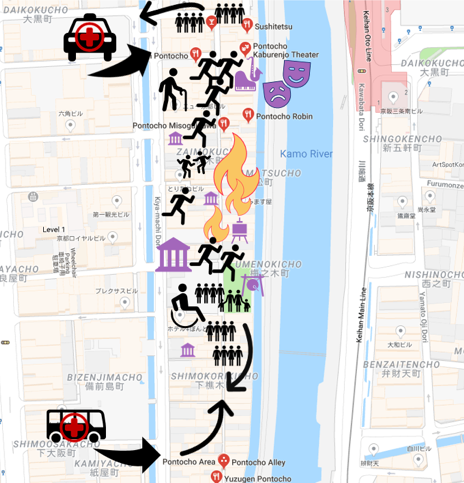

It is 7:45 p.m. in Ponto-cho, the historic narrow alley at the core of the Japanese city of Kyoto. Close to the Kaburenjo Theater – where still today Geikos and Maikos (Kyoto Geishas) practice their dances and performances – the traditional adjoining buildings with restaurants and shops are full of guests. Local people, tourists, students… On this Saturday in mid-April, the warm weather brings a lot of people to the streets nearby.

It is 7:45 p.m. in Ponto-cho, the historic narrow alley at the core of the Japanese city of Kyoto. Close to the Kaburenjo Theater – where still today Geikos and Maikos (Kyoto Geishas) practice their dances and performances – the traditional adjoining buildings with restaurants and shops are full of guests. Local people, tourists, students… On this Saturday in mid-April, the warm weather brings a lot of people to the streets nearby.

At 7:46 p.m., a M 5.1 earthquake strikes. Seven seconds of swaying. It doesn’t cause major damage, but it is enough to spread panic among a group of tourists. Screams, shoving, confusion… drinks spill, candles fall, people rush.

At 7:49 p.m., the fire starts spreading through the old wooden structures, also threatening the historic theater. Access is difficult due to the narrow streets and panicking crowd.

What happens next?

It could be a fire in the Ponto-cho traditional alley. It could be an earthquake shaking the historic center of Kathmandu (Nepal), the archaeological site of Bagan (Myanmar), or the historic town of Amatrice (Italy). It could be Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines or Hurricane Irma in the Caribbean, blasting sites with rain, flooding, and gale-force winds.

Cultural heritage assets around the world are at risk. They are often vulnerable due to their age, as well as previous interventions and restorations made without disaster risk or overall site stability in mind. Heritage sites reflect legacies, traditions, and identities. With all this, they carry a large cultural and emotional value of what could be lost – certainly beyond the traditional calculus of economic losses.

In many cases, it is not possible or advisable to conduct reconstruction on cultural heritage sites post-disaster. Therefore, the essence and soul of a cultural heritage site is at risk of being lost forever, making preparedness and preservation even more critical.

How can we protect these special places and traditions from the threat of natural hazards?

(Barbara Minguez Garcia / World Bank)

A disaster risk management approach can be fundamental for preserving heritage sites and – along with them – our human histories. Since such sites are often tourist destinations frequented by people who are unfamiliar with the area, comprehensive risk assessment and preparation can save lives. Unfortunately, there is often a gap in awareness and understanding of disaster risk – among site managers, surrounding communities, and the visiting public, including tourists and pilgrims.

The first step is to understand the risk – to the physical monuments and the integrity of the site, the cultural and economic activity in and around the site, and the well-being of local people and communities. To do this well, the local community – living and working nearby – must be part of the process to identify the risks and then protect and preserve the site, its character, and its integrity.

Interactive activities like the Disaster Imagination Game (DIG) can help communities – including neighbors, local authorities, and heritage specialists – to understand and communicate risk. This methodology, developed in Japan, brings together different stakeholders from a historic area to analyze and assess the situation, and then prepare people and places to face possible disasters. Ultimately, they discuss and decide upon potential solutions to avoid or mitigate risk, along with preparedness measures and plans for emergency response.

This exercise asks participants to reflect on key questions related to a specific cultural heritage risk scenario. For instance, consider the following about your hometown or a place you know well:

- What and where are the cultural heritage assets located? Are they structures, or are there also movable assets (e.g. museum artifacts)? Why are they important?

- Are there emergency evacuation routes for people at these sites? How about alternative evacuation routes to access and rescue critical heritage?

- Are you aware of the natural hazards in the area? How about secondary, or cascading, hazards (e.g. fires started after an earthquake)? How could those hazards affect the heritage?

- Who make up the community in the area? Are there elders or people with disabilities? Are there usually many tourists or visitors from out of town?

- What are, therefore, the main potential risks to the heritage sites and artifacts? What measures could or would mitigate those risks?

Interested in how communities are addressing this challenge around the world? Don’t miss this #UR2018 session:

Assessing and communicating risk to cultural heritage: The future of preserving the past

Thursday, May 17, 2018 / 11:15 am – 12:45 pm / Palacio de Minería

Join the Conversation