Also available in:

Español

Follow the authors on Twitter: @shomik_raj and @canaless

“It takes over 40 minutes just to get out of the parking lot. There has to be another way!" Listening to Manuel, an executive from Sao Paulo, was the tipping point that convinced us to convert our theoretical analysis on the potential of “corporate mobility” programs into real-life pilot programs in both Sao Paulo and Mexico.

“It takes over 40 minutes just to get out of the parking lot. There has to be another way!" Listening to Manuel, an executive from Sao Paulo, was the tipping point that convinced us to convert our theoretical analysis on the potential of “corporate mobility” programs into real-life pilot programs in both Sao Paulo and Mexico.

Corporate Mobility Programs are employer-led efforts to reduce the commuting footprint of their employees. Such programs are usually voluntary. The underlying rationale behind them is that improved public transport systems or better walking and cycling facilities are necessary but not sufficient to address urban mobility challenges and move away from car-centric development. Moreover, theory suggests that corporate mobility initiatives may have the potential for a rare “triple bottom line”: they reduce employers’ parking-related costs, improve employees’ morale and reduce congestion, emissions and automobility. In other words, corporate mobility programs are good for profits, good for people and good for the planet.

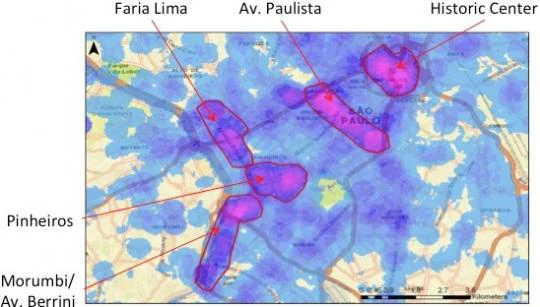

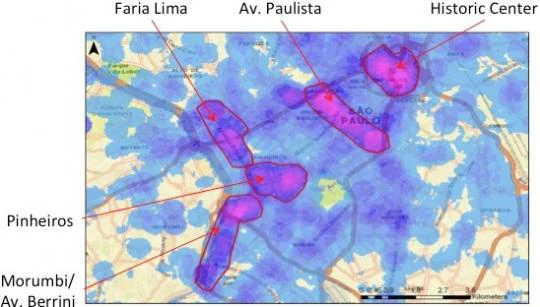

Our pilots were carried out in Mexico City’s Santa Fe business district and in two office complexes with about 6,000 employees in the Berrini Avenue section of Sao Paulo. Both areas were selected due to their high percentage of single-occupancy vehicles during peak hours compared to the rest of the city (see map below), and to the presence of a cluster of private employers who could be engaged in the mobility programs.

Careful monitoring of employees’ commuting patterns before and after the implementation of the program revealed the great potential of corporate mobility initiatives: in Sao Paulo, 4 of 10 participating firms saw a decline in single-occupancy vehicles of more than 15%, and another two witnessed more modest declines.

Building on the promising success of our pilot initiatives, it looks like corporate mobility is attracting more and more attention. Inspired by media reports on the pilots, some other Sao Paulo companies contacted us for assistance in designing and implementing a mobility plan for their employees. The World Resources Institute in Brazil decided to partner with the Bank on this and organized a high profile workshop in September 2013 where mobility secretaries of Sao Paulo city and state, Belo Horizonte and Curitiba endorsed the initiative. In Mexico, the city government is currently exploring ways to incorporate elements of a corporate mobility initiative into its sustainable mobility agenda. Other Latin American cities have also approached us and expressed interest in corporate mobility.

As we look to institutionalize and scale-up such “demand management” initiatives, we wanted to highlight three “pillars” that we think are essential to the success of corporate mobility efforts:

Organizing the alternatives. A lot of our effort focused on facilitating and coordinating the alternatives to single-occupancy commuting:

Motivating the participating firms. Given the voluntary nature of the pilots, we had to come up with creative ways to motivate both employers and employees to continue participating:

The pilot Coporate Mobility Programs presented in this article were implemented with the help and financial support from the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP).

Learn more:

Follow the authors on Twitter: @shomik_raj and @canaless

“It takes over 40 minutes just to get out of the parking lot. There has to be another way!" Listening to Manuel, an executive from Sao Paulo, was the tipping point that convinced us to convert our theoretical analysis on the potential of “corporate mobility” programs into real-life pilot programs in both Sao Paulo and Mexico.

“It takes over 40 minutes just to get out of the parking lot. There has to be another way!" Listening to Manuel, an executive from Sao Paulo, was the tipping point that convinced us to convert our theoretical analysis on the potential of “corporate mobility” programs into real-life pilot programs in both Sao Paulo and Mexico.

Corporate Mobility Programs are employer-led efforts to reduce the commuting footprint of their employees. Such programs are usually voluntary. The underlying rationale behind them is that improved public transport systems or better walking and cycling facilities are necessary but not sufficient to address urban mobility challenges and move away from car-centric development. Moreover, theory suggests that corporate mobility initiatives may have the potential for a rare “triple bottom line”: they reduce employers’ parking-related costs, improve employees’ morale and reduce congestion, emissions and automobility. In other words, corporate mobility programs are good for profits, good for people and good for the planet.

Our pilots were carried out in Mexico City’s Santa Fe business district and in two office complexes with about 6,000 employees in the Berrini Avenue section of Sao Paulo. Both areas were selected due to their high percentage of single-occupancy vehicles during peak hours compared to the rest of the city (see map below), and to the presence of a cluster of private employers who could be engaged in the mobility programs.

Areas of Sao Paulo with the highest indices of single-occupancy vehicles (SOVs)

and traffic congestion during peak times

and traffic congestion during peak times

Point density plot of automobile trips from 2007 OD Survey

Area around Berrini > 53% of trips by SOV

Note: These are working trips starting at home between 7:00am and 9:30am

Careful monitoring of employees’ commuting patterns before and after the implementation of the program revealed the great potential of corporate mobility initiatives: in Sao Paulo, 4 of 10 participating firms saw a decline in single-occupancy vehicles of more than 15%, and another two witnessed more modest declines.

Building on the promising success of our pilot initiatives, it looks like corporate mobility is attracting more and more attention. Inspired by media reports on the pilots, some other Sao Paulo companies contacted us for assistance in designing and implementing a mobility plan for their employees. The World Resources Institute in Brazil decided to partner with the Bank on this and organized a high profile workshop in September 2013 where mobility secretaries of Sao Paulo city and state, Belo Horizonte and Curitiba endorsed the initiative. In Mexico, the city government is currently exploring ways to incorporate elements of a corporate mobility initiative into its sustainable mobility agenda. Other Latin American cities have also approached us and expressed interest in corporate mobility.

As we look to institutionalize and scale-up such “demand management” initiatives, we wanted to highlight three “pillars” that we think are essential to the success of corporate mobility efforts:

Organizing the alternatives. A lot of our effort focused on facilitating and coordinating the alternatives to single-occupancy commuting:

- In addition to existing public transit options, we also identified a number of private-based alternatives, including carpooling, commuter bus solutions, teleworking, carsharing, and even inspirational “bike angels”, who volunteer to bike with new cyclists to show them the ropes and give them confidence.

- We helped property managers conceptualize improvements in shower, locker and parking facilities for cyclists, and helped companies develop products such as a parking cash out (whereby employees eligible for a parking spot could give it up in exchange for cash-equivalents like a gym membership).

- In addition, we developed a “guaranteed ride home” program: the program allows employees who do not drive to work to receive a certain number of taxi vouchers each year in case they have to work late or face an emergency.

Motivating the participating firms. Given the voluntary nature of the pilots, we had to come up with creative ways to motivate both employers and employees to continue participating:

- One step towards that was to enlist the help of professionals who have had much experience with such programs in the US and were able to help us design messages tailored to the interests of particular interlocutors at the firms.

- A second important tool was a comprehensive media initiative. Our colleague Andrea Leal spearheaded a very successful communications campaign – you can watch Andrea present the program in this TV segment (Portuguese).

- Other potential tools include: branding initiatives like “Great Place to Work”, which recognizes firms that support employees to manage the burden of their commutes; and possibly mandatory requirements like this program in Seattle.

The pilot Coporate Mobility Programs presented in this article were implemented with the help and financial support from the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP).

Learn more:

- Report: A commuter-based Traffic Demand Management Approach for Latin America: Results from Voluntary Corporate Mobility Pilots in São Paulo and Mexico City

- Feature story: Changing Commuters’ Choices Helps São Paulo Reduce Traffic Congestion

- Great Place to Work Program

- Commute Trip Reduction (CTR) Program in Seattle

- News article: In an Effort to Alleviate Traffic, Brazilian Companies Ask Their Employees to Work from Home (El País, Spanish)

- Video: Andrea Leal Bets on Corporate Incentives to Reduce Traffic (Portuguese)

- Video: Globonews Panel - Guests Talk About Urban Mobility Projects and the Problems Caused by Traffic (Portuguese)

- Bike Angels, Brazil: Welcome to the World of Cycling! (Portuguese)

Bem-vindo ao Mundo da Bicicleta / Welcome to the World of Cycling

Join the Conversation