Whether it be from The Wall Street Journal, or YouTube, by now most of us have heard the arguments for and against development of “shale gas”, and as a member of the World Bank’s Oil, Gas and Mining Unit, hardly a day goes by that I do not receive a notice about an article, a presentation or a conference on this topic.

Shale gas is natural gas “trapped” inside impermeable rock, known as shale. Almost overnight, it has become an economically viable and popular source of fuel in the United States. Producers use a combination of horizontal drilling and high-pressure fracturing technologies to recover gas once thought too costly to produce. Production has rocketed from virtually nothing five years ago, to over one quarter of all US gas supply today.

Although shale development has been a US phenomenon to date, early scientific evidence indicates that shale gas deposits exist globally (the US EIA estimates shale gas could increase world recoverable reserves by over 40%), representing potentially important new energy supplies to countries currently dependent on imports or alternative fuels including heavy fuel oils and coal. But the production of gas is an industrial process that cannot occur unseen, unheard and without risk. The development of shale gas resources, especially in areas unfamiliar with extractive industries, comes freighted with controversy.

Proponents argue that this unexpected increase in supply has kept US gas prices low, saving the country billions of dollars in energy costs annually, and prompting many power generators to switch from coal to gas, eliminating millions of tons of CO2 from entering the atmosphere. At the local level, tens of thousands of jobs have been created, land and mineral rights owners have prospered, as have local governments and civil groups funded by taxes and contributions related to this industry.

Meanwhile, opponents of this extraction claim drilling and completion operations are dangerous and polluting, and that ongoing production is invasive and disruptive to communities. There have been assertions that water contamination, minor earthquakes, and unacceptable levels of air, noise and light pollution result from shale gas operations, and that low gas prices undermine the introduction of renewable energy.

In this context, and under the initiative of World Bank Special Envoy Mahmoud Mohieldin, a team of World Bank energy department staff members visited a highly productive section of Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale. We hoped to see for ourselves how industry, government and civil society are coping with the explosive growth of this industry, to help us develop responses to World Bank clients that have asked for preliminary guidance in this area.

We left the Bank’s Washington headquarters in late afternoon, travelling by road across the hills of Northern Maryland and Southern Pennsylvania to reach our hosts at the Nemacolin Energy Institute in time for a dinner reception with local community and industry representatives. After a brief explanation of the World Bank’s work in the energy sector, conversations quickly change to the unexpected and phenomenal growth of gas development operations in the region.

Here are just a few examples of the stories we hear:

Bill took a big bet that his “air-drilling” business, primarily to drill water wells in the area, would be the choice for the vertical portion of Marcellus shale gas wells, and expanded his business to service the oil field. His gamble was successful, and Bill’s business and staff have multiplied several times in the past five years…and he is hiring.

A local tire company had been barely profitable replacing personal car and truck tires and an occasional tractor tire in their rural community. Today, they service the high-margin off-road needs of company pickups, and commercial vehicles that support the industry.

The Nemacolin resort now hosts a variety of industry events and has become the home of the Nemacolin Energy Institute, a group that helps leaders develop local, regional and national energy policy.

We end our night feeling positive about shale gas’s potential to support ancillary services and inject money into local economies beyond taxes and royalties to governments and landowners lucky enough to control the rights to subsurface minerals on their property. We decide to “sleep on” our initial reactions, and reserve judgments until after our visit to the field.

I make a note to report that the Rice facilities looked pretty impressive, yet I wonder how this scene may be viewed by local landowners who have seen hilltops leveled for production pads, pastures crisscrossed with gravel roads, and pavements now shared with trucks of all sizes and other heavy equipment.

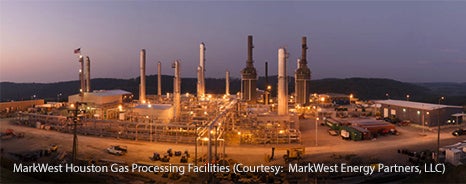

After a quick lunch during our bus transit, we meet the Managers of Operations, Environmental Protection and Safety from MarkWest Energy Partners, at a Hilton hotel in a “newish” commercial park in Canonsburg. MarkWest gathers “raw” gas here and processes it for sale as the natural gas we know as consumers. Their facility removes natural gas liquids (NGLs) which are sold for residential and refinery use and as feedstock to petrochemical plants. In fact, so much NGL are being recovered from shale gas, that the US petrochemical industry has been revitalized and is undergoing expansion. We learn that the plant and workforce have doubled several times over during the last few years, providing needed employment to the area which had been suffering from the closure of local steel mills.

Our team found no sign of protest, no indication of malpractice, or any evidence of pollution during our visit, although it is true that we were visiting producers, not critics. Instead, we saw and heard examples of how a potentially disruptive operational practice has been able to provide real economic and social benefits to these communities. Was there a rocky start to shale development in the area? I am sure there was. Are there still problems with this form of industrial growth? I am sure there are. Will there be issues and concerns going forward? I bet there will. But it is clear to me that five years into this wild ride, business, government and civil society have found ways to cooperate and share the benefits of development.

What might this mean for the developing countries in which the World Bank is active? Much scientific investigation and testing will be required before the industry can find and develop sizeable, commercial shale gas resources. Even then, supportive government policy and regulation and the establishment of highly technical support services will be required before the resource can be developed to a significant degree. Particularly encouraging from the US experience, however, is evidence that shale gas developments can be achieved by a host of smaller companies which, in turn, support the establishment and growth of other enterprises leading to significant local employment and economic growth. Perhaps imperfect, shale gas may be the best hope for many poor countries for secure and cleaner energy supplies in decades to come.

Related

Join the Conversation