This post is part of our Closing the Gap: Financial Inclusion blog series, which shares the views of experts and practitioners on different financial inclusion topics.

Financial institutions and market authorities have moved payment systems from the backroom to the boardroom in recognition of the critical role that a well-functioning payment system plays in supporting financial systems and real economies. A sound and efficient infrastructure to process modern payment instruments has the potential to enhance financial inclusion. Widespread use of electronic payment instruments could also create significant savings for governments and other stakeholders.

The World Bank has been paying increasing attention to payment system development as a key component of a country’s financial infrastructure, and has committed to periodically collect and update information on the status of payment and settlement systems worldwide to both enhance knowledge on these matters and help guide reform efforts.

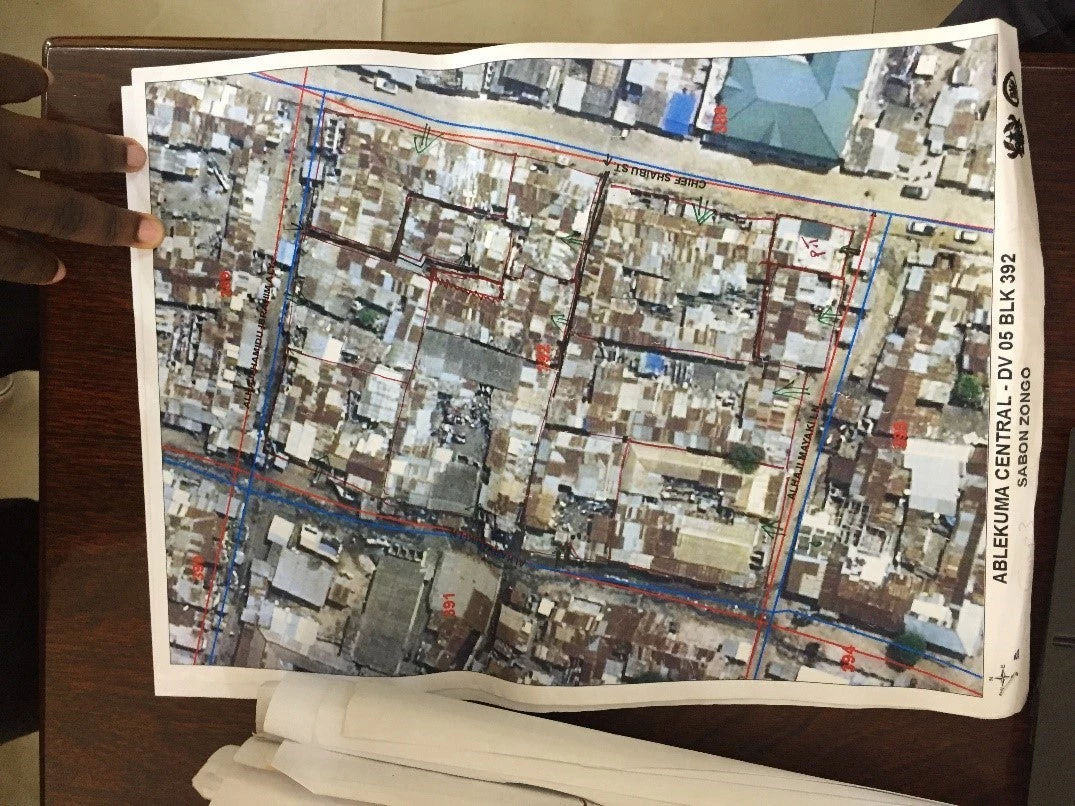

(Click here and go to page vii to view larger)

The most recent World Bank Global Payment Systems Survey contains information on: the legal and regulatory framework underpinning a national payments system, large-value payment systems, retail (or low-value) payment instruments and services including the latest innovations, foreign exchange settlement systems and international remittances and cross-border payments, among other topics. The study is important because it provides a ‘snapshot’ of payment systems worldwide covering 139 countries and serves as an important reference in shaping the international agenda on payment systems issues. The next iteration of the World Bank Global Payment Systems Survey will be launched in July 2012.

Snapshot: Key Findings

Data and information collected in 2010 clearly show that national payments system reforms have led to progress in large-value payment systems. 116 countries of different income levels and geographic locations report using a real-time gross settlement (RTGS) system for high value payments. This is up from the early 90s, when less than 5 countries had RTGS systems. These systems collectively process transactions worth over 40 times the global GDP in a safe and efficient manner. The shift to RTGS systems significantly reduces systemic risk.

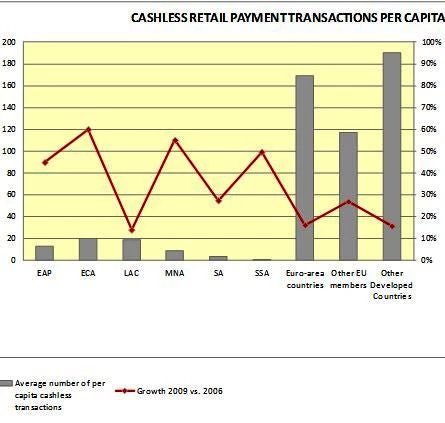

On the other hand, the retail payment systems area is where the largest differences continue to exist between higher-income and lower-income countries, and between developed and developing regions. While the vast majority of countries indicate that they are already operating one or more cashless payment systems, differences in volumes and value of transactions handled through such systems are still extremely large when comparing developed countries/regions to developing ones. While in most OECD countries it is typical to see 100 or more cashless transactions per capita in a year, in many low income countries this number drops to less than 1.

Also, when looking at the number of transactions for non-cash payment instruments, it appears that low- income countries (65%) show the highest usage of cheques, the cost of which they indicate as being generally lower than direct credits/debits (only 5% of low-income countries reported the cost of cheques as being high). Interestingly, the opposite is true for high-income countries.

This situation is explained by a number of factors, including:

i) The slow development of access channels to initiate and deliver cashless payments – e.g. POS terminals, and limited interoperability;

ii) Limited competition among banking institutions and payment service providers – resulting in higher costs and more limited coverage; and

iii) The widespread use of cash and cheques for government/utilities companies/large commercial firm’s payments – when automated, these could bring enormous benefits in terms of adoption and efficiency. Based on the survey’s findings, less than 10% of the innovative payment products reported support government to person (G2P) payments, and about 17% are used for business to government (B2G) payments.

Survey results show that cash is the most relevant payment instrument for both sending and receiving remittances, in 44% and 46% of the countries surveyed, respectively. Meanwhile, current account transfers for sending and receiving remittances were ranked a distant second by 26% and 32% of the respondents, respectively. The use of cash is clearly lower in high-income countries where current account transfers take first place. Remarkably, the great majority of the countries surveyed do not consider the use of prepaid cards and mobile phones significant for sending or receiving remittances. “Traditional” remittance service providers (RSPs) such as commercial banks and international money transfer operators (MTOs) are considered by far the most relevant RSP types by central banks at the global level (about 55% and 24%, respectively). Local MTOs and post offices are considered to have a limited role. Even more limited at a global level is the role of credit unions, microfinance institutions, and mobile phone operators.

The survey also shows that inadequate transparency in the market for remittance services (e.g. RSPs are legally required to disclose all transaction costs before the transaction itself is performed in only 56% of the cases) is often a result of the lack of an appropriate consumer protection framework for financial services users: Consumer protection legislation for financial services is only in place in less than a third of the countries surveyed. While the survey does not include information on the price of remittances, the World Bank publishes the cost of sending money to and from countries in "remittance prices databases", both at the global level and the regional level with a view to increasing transparency in the markets for international remittances.

On the other hand, it is encouraging to note that remarkable progress has been made in the area of payment system oversight: this function has been established in 99 central banks and is carried out on an on-going basis. The evolution of the oversight function towards broader objectives including fair competition and consumer protection may further expand to cover conditions and pricing of retail payment services.

It is clear that in this sector, market forces alone have not achieved the objective of an efficient and reliable payments system. In order to accelerate progress in the retail payments area, the payments system overseer must be entrusted with, and have sufficient powers and resources to make up for a specific type of failure in the market for payment services, i.e. the coordination failures among financial institutions.

Millions of the world's poor are unbanked. What can countries and citizens do to close that gap? Join the conversation by following our financial inclusion blog series or tuning into the Closing the Gap: Financial Inclusion event on Thursday, April 19 at 2:00 EST

Join the Conversation