Reducing inequality is a key policy priority in many countries as high levels of inequality can be detrimental to society. The existence of large differentials in living standards can be a drag on the opportunities of the next generation, lower overall satisfaction with life, and in some cases, lead to disruption and violence. But how can a country succeed in reducing its inequality? Lesotho – a small, mountainous kingdom of 2.1 million people completely enclaved in South Africa – provides an interesting case study.

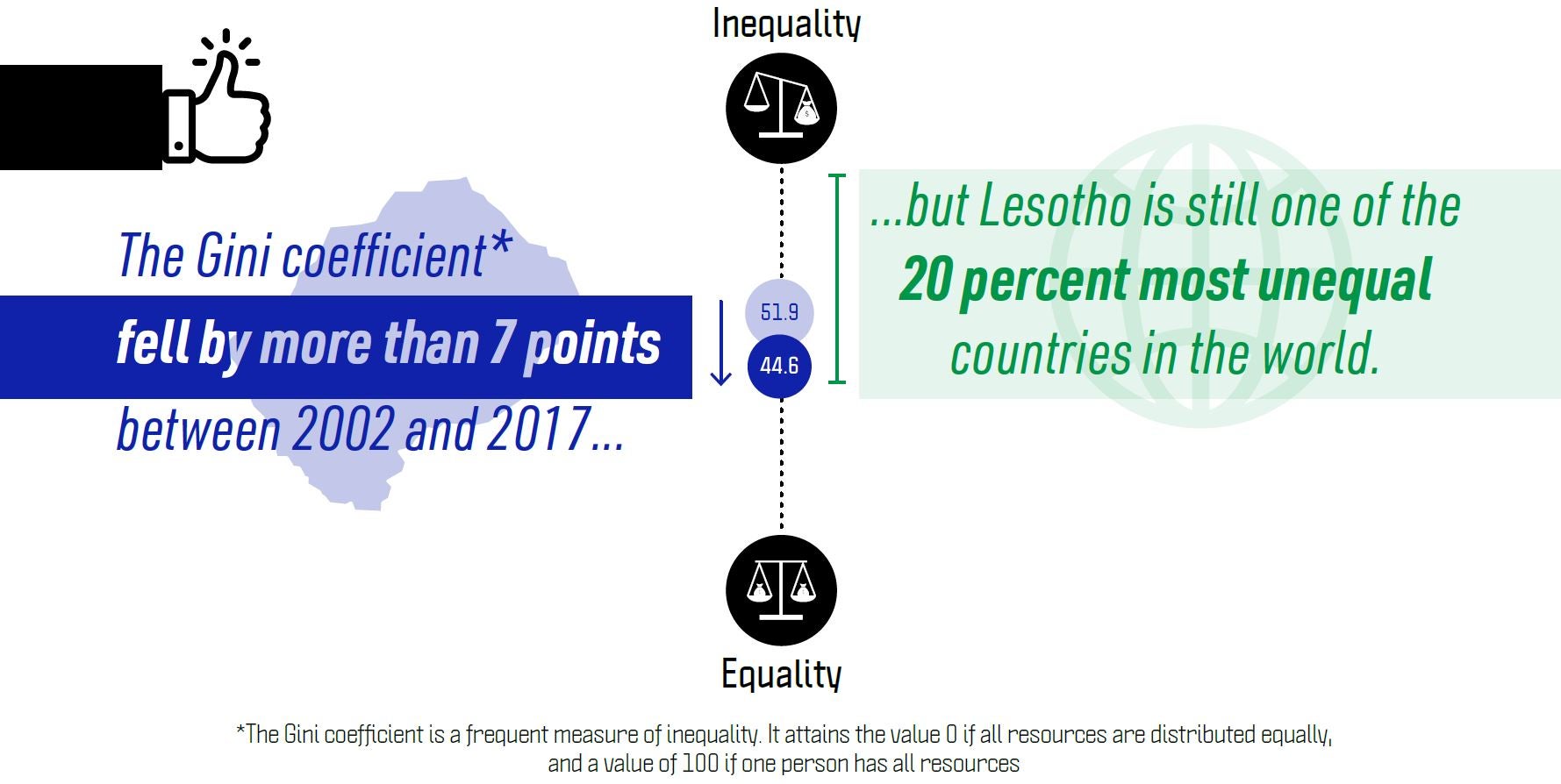

The Gini coefficient is a frequent measure of inequality, which obtains the value of zero if all resources are distributed equally and a value of 100 if one person has all resources. For years, together with its Southern African neighbors, Lesotho was one of only a handful of countries in the world with a Gini coefficient above 50. However, a recent assessment of poverty and inequality in the country suggests that it has made considerable progress towards a more equal society. In 2017 the Gini coefficient stood at 44.6, which, although still high in a global context, marks an impressive decline from 51.9 fifteen years earlier.

The decline in inequality was even more impressive when considering the many factors that were pulling against this decline. In 2015-2016, Lesotho had just experienced one of the worst droughts in its history, particularly hurting the rural poor, which had an adverse impact on inequality. The decrease in the Gini coefficient also occurred after employment opportunities in South Africa diminished, which used to be one of the main sources of income of the poor. Finally, it contrasts with the trend in South Africa, where inequality has increased since 1994.

So why did inequality fall?

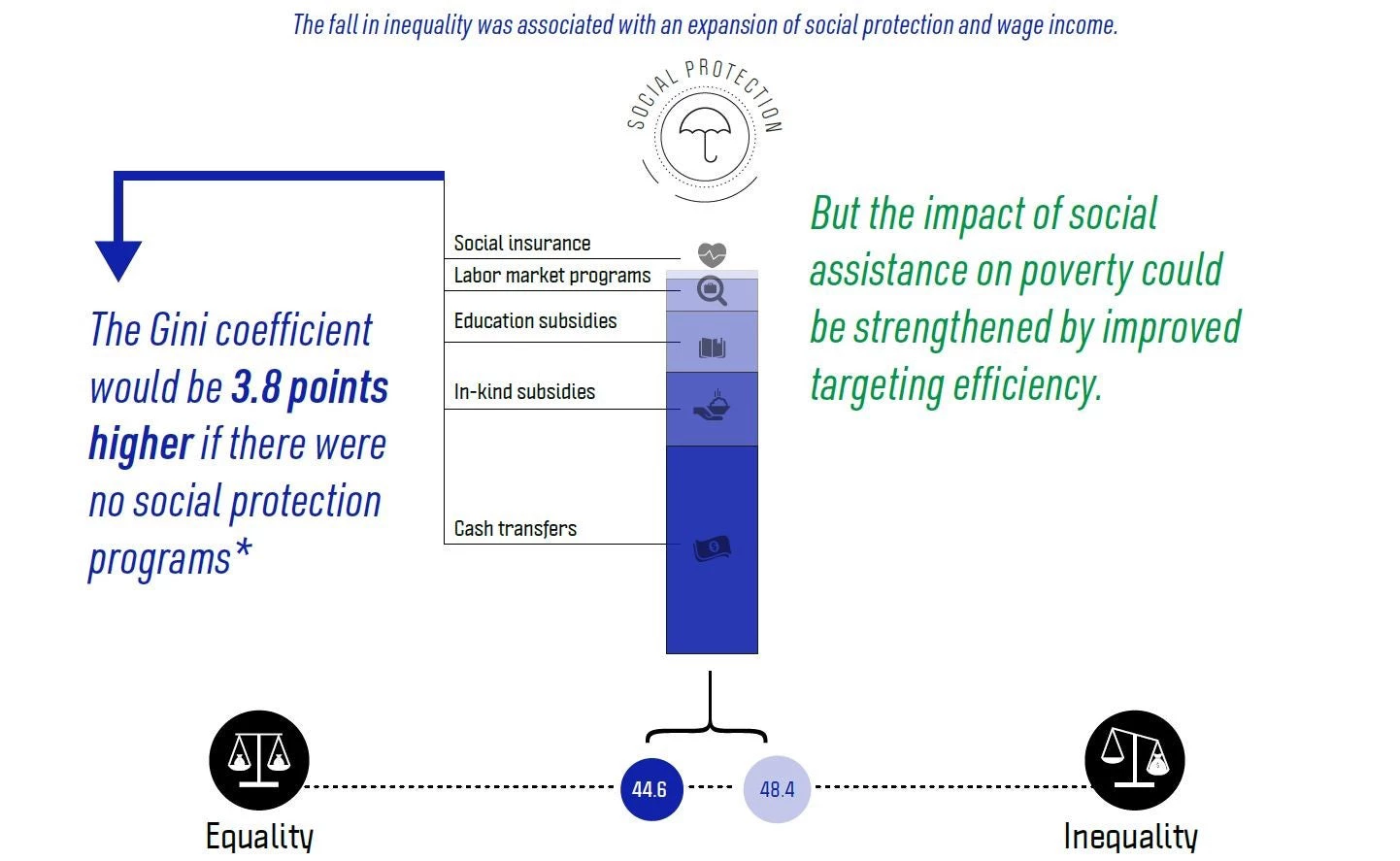

Increases in formal wages among the poor, expansion of primary schooling, and favorable demographic changes all contributed to lowering inequality. Yet, the study finds that the biggest reason for the decline has to do with introduction and expansion of social protection programs.

By one measure, Lesotho spends 4.5% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on social protection programs, in contrast to below 2% in the average country in Sub-Saharan Africa or the average lower middle-income country. The programs reach a large share of the poor and the Gini coefficient would be around 3.8 points higher if these programs did not exist at all. In particular, the growth in income from social protection programs that occurred between 2002 and 2017 led to a 2.6-point decline in the Gini coefficient.

The decline in inequality is mainly driven by old-age pensions, a noncontributory social assistance program introduced in 2004 which provides monthly cash transfers to those age 70 or above – a segment of the population which has some of the highest poverty rates. The program covered over 80% of the target age group, reaching 15% of all households, and provided a benefit amount roughly equal to the national poverty line in 2017. The school feeding program, which covers all children in government primary schools by providing cooked lunches at school, also has a noticeable impact on reducing inequality.

Still, many of the social protection programs could be better targeted, particularly postsecondary education bursaries, which are costly and tend to favor nonpoor households. Hypothetically retaining bursaries only for poorer students and reallocating the outlay this saves to a transfer targeted to poorer households through the government’s proxy means test formula, could reduce poverty and inequality significantly more than current spending under this program. Other programs also have room for improvement in better reaching the poor.

Due to a large urban-rural divide, public-private sector wage gaps, and inequalities in educational attainment, Lesotho is still one of the top 20% most unequal countries in the world. As such, a lot more still needs to be done in assuring that all Basotho have the same chances of succeeding in life. But the case of Lesotho shows that inequality can be tackled.

Join the Conversation