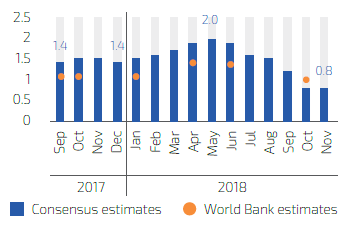

Figure 1: Forecast for South African 2018 GDP growth

We have argued for some time that South Africa is a low-growth economy, as many South Africans do not participate in the economy and high inequality fuels policy uncertainty around the future of redistribution. We estimate the South African economy to grow at about 1.4% on average between now and 2030 , unless significant policy action is undertaken. This growth barely keeps pace with population growth, leaving very little scope to generate the jobs and resources needed to reduce poverty in South Africa and create a more equal society. The need for higher growth—especially when other emerging markets tend to grow much faster—is undisputable.

Yet an optimism bias in growth forecasts is dangerous. In a recent paper we explore the impact the commodity super-cycle had on fiscal policy in emerging markets and South Africa more specifically. We argue that the unusually long duration of high commodity prices between 2000 and 2015 has led economists to believe that these high prices were a ‘new normal’ and accordingly, high prices were factored into baseline growth forecasts. When the super-cycle ended in 2015, it became clear that forecasts had been overly optimistic. This also meant that medium-term expenditure frameworks had been more generous than commodity-exporting economies could afford, and that their governments should have saved more to prepare for the downturn when commodity prices eventually dropped. We argue that this also happened in South Africa and that South Africa’s relatively high debt level can partly be explained by this. This indebtedness now severely restricts the power of fiscal policy to stimulate the economy.

In our 12th South Africa Economic Update, we estimate 2019 growth at 1.3%. This is below the expectations of both National Treasury and the South African Reserve Bank (both 1.7%). Our forecast assumes that the implementation of structural reforms under the Ramaphosa administration progresses but that these reforms will take time to yield results, while deteriorating global conditions will also put pressure on the South African economy. However, we assume that the reforms will eventually raise gross domestic product growth: our 2020 forecast is 1.7%. We would be happy for our forecasts to eventually be overly cautious—yet it is better to err on the side of caution.

Join the Conversation