Flood in housing park in Kelantan, Malaysia due to heavy rains | © shutterstock.com

Flood in housing park in Kelantan, Malaysia due to heavy rains | © shutterstock.com

Twenty-three percent of the world population, or 1.81 billion people, are directly exposed to substantial risks during a 1-in-100-year flood event. Flood exposure and damages are also likely to increase as a result of more frequent floods, an increase in flood-prone areas, and the rapid growth of populations and economic assets in flood-prone areas. And the risk is not equal for all urban populations. Low-income households are more likely to live in high-risk zones, incur higher damages and be less able to recover.

In this context, a new study, supported by the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) examines the efficiency and distributional impacts of three ex-ante flood management policies in an urban context with two income groups. It considers various spatial configurations where poor and rich households either live in the central part of the urban area or in its periphery and flood-prone areas can be central, peripheral, or uniformly distributed throughout the urban area.

Efficiency of flood management policies

The three ex-ante flood management policies that we studied are a risk-based insurance scheme, where insurance premiums are incurred by homeowners and perfectly reflect risks of damages to buildings; a land zoning scheme, where construction is prohibited in flood prone areas; and a subsidized insurance scheme, where all of the households contribute through income taxation to a fund aimed at compensating losers from flood damages to buildings.

Consistent with previous work, we find that the first best policy for maximizing social welfare is the risk-based premium insurance. The risk premiums, by reflecting the anticipated costs of disasters, will encourage homeowners to build less in flood-prone areas. This policy perfectly internalizes the damage risks.

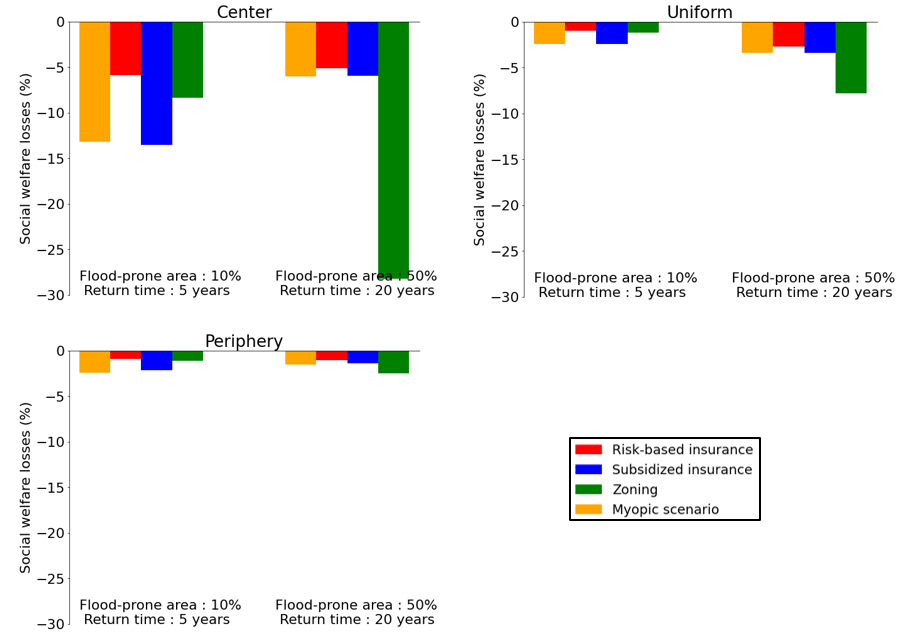

In the real world however, implementing risk-based insurance is often not feasible for technical, social, or political reasons. And even if it were, a sudden introduction of this policy would likely have limited impacts on flood risks and strong negative welfare impacts. Instead, subsidized insurance for widespread and rare floods, or zoning in the case of frequent and localized flood events, are close to optimal. This result confirms that more feasible, second-best options need not come at large expense of efficiency in aggregate. Zoning avoids structural damage but creates land scarcity for building purposes and drives housing rents up. Subsidized insurance—in the form of a flood compensation fund that every household contributes to—maintains a large building stock and consequently low housing rents, but it also increases damage to structures in flood-prone areas (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Social welfare losses from floods when the poor households live in the city center and the rich in the periphery, considering three flood locations (central, peripheral, and uniformly distributed) and two flood event types (frequent and localized, or, rare and widespread).

Source: Authors’ calculations.

No political economy deadlock… but redistributive and inequality issues all the same

The good news is that the hierarchy of flood management options coincides between high- and low-income groups, irrespective of urban configuration—high-income households living in the city center or the periphery—and flood location. This result is important because it shows that the type of flood management chosen should not lead to political economy problems, where antagonistic preferences between household groups lead to a suboptimal solution.

Flood management policies introduce flood risk information to various degrees and can trigger land and housing market adjustments. These market adjustments redistribute costs between income classes, irrespective of who is directly affected by floods. As such, flood management policies can be progressive, for example, can reduce inequalities, if the low-income group is hardest hit, or regressive if the high-income group is hardest hit compared to a situation where no flood management policy is available.

Although the hierarchy of flood management policies coincides between income groups, it can nevertheless come at the expense of increased inequalities. Whereas both income groups prefer risk-based insurance, for centrally located floods in the low income-high income configuration where low-income households live close to jobs, this type of insurance will deepen welfare inequalities. Low-income households will be better off with risk-based insurance than any other policy in absolute terms, but they will still lose comparatively to high income groups. In this setting, only subsidized insurance would maintain inequality levels constant across income groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Inequality and welfare impact of the three policies when floods are located in the city center when the poor households live in the city center and the rich in the periphery.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Note: For the three policies, each dot corresponds to a specific flood event, characterized by its return period (frequency) and extent (fraction of land which is flood-prone)

These results point to possible, though not systematic, equity-efficiency trade-offs which are made more apparent as flood events become more damaging, either because of increased flood frequencies, increased flood-prone areas, or more intense events—all likely to materialize in certain parts of the world due to climate change. So, while the inequality impacts of flood management policies may appear as negligible for current climate conditions, they could prove much larger in the future. Considering the path dependance displayed by structures and urban areas, and assuming that inequality levels can reach unsustainable levels from moral or political perspectives, it is important to take these findings into consideration when designing flood management policies to avoid greater inequality in the future.

Join the Conversation