Your neighbor drives for a ride-sharing company. Your nephew just joined his third start-up. Your daughter lands a job as a freelance journalist. Your street vendor who sells flowers down the street has been absent due to an illness.

The changing nature of work is upending traditional employment. But as the gig economy, part-time jobs, contracts and other diverse and fluid forms of employment grow, what happens to the protections the traditional job market offered to people and workers?

Most social protection systems in rich countries were developed at a time of “jobs for life,” with social insurance based on mandatory contributions and payroll (labor) taxes on formal wage employment.

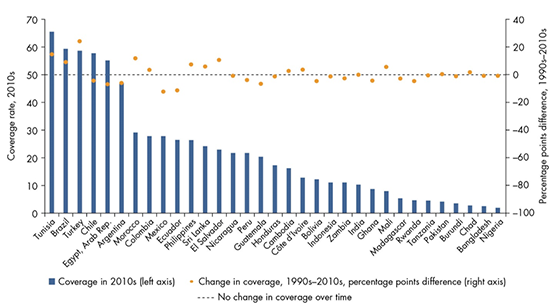

But around the globe, this traditional, payroll-based insurance system is increasingly challenged by working arrangements outside standard employment contracts. In the U.S., pension plans are becoming a thing of the past. In developing countries, traditional social protection systems are seldom adopted at a significant scale. In India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nigeria — which combined account for about a third of the world’s population — coverage of social insurance is single digit or almost so, with virtually no change detected over the past decades (figure 1).

Figure 1. Social insurance coverage in developing countries is generally low

Source: World Bank pension database

New ways of protecting people are needed. We need a new social contract and greater investment in people. As we examine the changing nature of work in our 2019 World Development Report, we are taking a look at how we can better protect people and workers in the new economy. Here’s what we’re finding:

- Informality, which currently engulfs around 80% of labor markets in developing countries, is a premier bottleneck. Most workers — especially the poor — are engaged in informal sector activities with no or little access to social protection. Given the endemic nature of challenge and slow progress against it, most people would be better-off with a social protection system that does not depend on their work situation.

- Social assistance, which ensures equity in societies, could be enhanced to include larger swaths of informal sector workers. There is a range of options starting with a means-tested Guaranteed Minimum Income (GMI) programs and ending with a Universal Basic Income. An intermediate option could be a Negative Income Tax that has relatively high threshold and gradual withdrawal of benefits, or a smaller GMI supplemented with other programs, such as universal child allowances and social pensions.

- The notion of ‘progressive universalism’, borrowed from the health sector experience, may help guide the expansion in ways that benefit the poor and vulnerable first.

Once guaranteed, solid basic protections are in place, people could keep upgrading their security with various progressively-subsidized schemes – with contributory social insurance where conducive conditions exist, but also an array of voluntary options where the state and markets can offer them.

As more investments are made in social protection, a balanced approach to labor market regulations could help meet productivity and equity goals. Minimum wage is and should remain a vital tool for balancing power between firms and workers. Just like social insurance, some regulatory measures may benefit only ‘insider’ formal sector workers. For example, it’s hard to enforce the minimum wage in high-informality contexts. Guaranteed social protection can help take pressure out of minimum wages when these are set too high.

Financing more investment in social protection is a formidable challenge for poor countries. But several options exist. Closing loopholes and exemptions in regressive VAT will generate considerable revenue: for example, Vietnam could increase tax revenues by 11 percent by moving to a uniform VAT rate of ten percent. Excise taxes, for example on tobacco, are another source of potential revenue. In 2015, Sub-Saharan African countries collected less than half the level of excise taxes as compared to Europe, at just 1.4 percent of GDP.

Carbon taxes have become increasingly prevalent. It is estimated that nationally-efficient carbon pricing policies could raise substantial amounts of revenue—above six percent of GDP in China, Russia, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. These taxes could be paired with the elimination of energy subsidies, which amount to $333 billion globally. Spending on energy often dwarfs that on social assistance: in the MENA region, the ratio is three to one. Other forms of recurrent taxation may include immovable property taxes as well as a fair corporate tax system, which is currently plagued by loopholes in the international tax architecture.

Just as technology improves delivery systems for social protection programs, it can also facilitate tax collection by increasing the number of registered tax payers and social security contributions.

The social protection community shares fundamentally similar values, although the exact policy contours may slightly vary. The future of social protection elicits passionate debate (e.g., see here and here) but, at a time when future risks meet unsolved present quandaries, it is important to face challenges head on.

At the World Bank, we count on our valuable global and national partners. Together, we can shape the future of social protection in ways that ensure broad gains for societies in general, and the poorest in particular.

Join the Conversation