Elementary school children carry out morning exercise. | © shutterstock.com

Elementary school children carry out morning exercise. | © shutterstock.com

Why do some countries succeed in implementing challenging education reforms to improve student learning, while others falter? The WDR 2018 broke new ground by exploring in depth the political and technical barriers to ensuring that all children learn. In Fixing the Foundation, the new education regional flagship covering middle-income East Asia and Pacific (EAP), we offer new evidence on the factors impeding reforms in the region. So, what is going on? Is it ignorance of the problem? Is it a lack of knowledge of how to address the problem? Is it low implementation capacity? Are there perverse incentives?

We learned a few surprising things.

Awareness Gap among EAP’s Policymakers

Reform has to start with widespread awareness of low learning. But in EAP, a significant disconnect exists between policymakers' perceptions of how much students know and the reality of educational proficiency. Policymakers in seven EAP countries, including those from ministries of education, ministries of finance and parliamentarians, estimate that only 28% of 10-year-olds cannot read proficiently, while the actual figure is a staggering 60%. The disconnect is greater than the global average. Like their global counterparts, EAP policymakers often overlook foundational skills like literacy and numeracy, instead focusing on nation-building and technical training.

Declining Influence of Teacher Unions

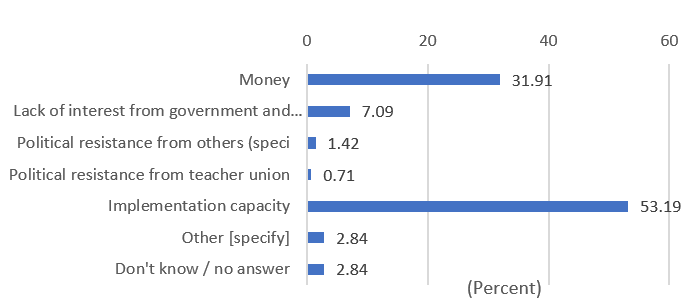

In the WDR 2018, we wrote about how powerful teacher unions had stalled quality-focused reforms in several countries and promoted better outcomes in others. But unlike these countries, teacher unions in EAP have seen a decline in influence over the past decade. Once powerful in countries like Cambodia and the Philippines, teacher unions now play a diminished role in education politics. Driven by government policy, unions here have lost much of their voice. When asked, policymakers in East Asia did not view union power as a major barrier to educational reform (see figure 1).

Figure 1: What do you think is the single biggest barrier to improving student learning outcomes?

Source: https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/eap/publication/fixing-the-foundation

Vested Interests in the Education System

Despite weakened unions, informal mechanisms appear to significantly influence teacher recruitment, deployment and promotions in EAP. Education systems in countries like Indonesia, Philippines, Cambodia, and Mongolia intertwine closely with the political system, creating a cycle of mutual benefits for politicians and educators. It is hard to get evidence on this, as much of it happens in the shadows. But Fixing the Foundation provides some telling results. As figure 2 shows, merit might matter, but political connections are also important. Interestingly, teachers in EAP retained their political power even when unions did not. How? When unions don’t signal teacher priorities, politicians are in the dark on what teachers might do, so they play safe and avoid measures that could be unpopular with teachers.

Figure 2: Political connections influence teacher selection

Who is most likely to get the job?

Candidate A has good test scores, but is not well-connected politically

Candidate B does not have good test scores, but is well-connected politically

Source: https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/eap/publication/fixing-the-foundation

Low implementation capacity

The subversion of meritocratic processes in recruitment and deployment has likely weakened implementation capacity in EAP. Policymakers acknowledge low implementation capacity as a primary challenge in improving educational outcomes (see figure 1). The compromised integrity of personnel-related processes affects the effective implementation of reforms.

Limited Parental Voice

In EAP, parents have minimal influence over the education system, a trend aligned with a general decrease in voice and accountability in EAP’s developing countries as shown by the Worldwide Governance Indicators. School management committees, once platforms for parental involvement, have been co-opted by teachers and principals in countries such as Indonesia, further eroding accountability mechanisms.

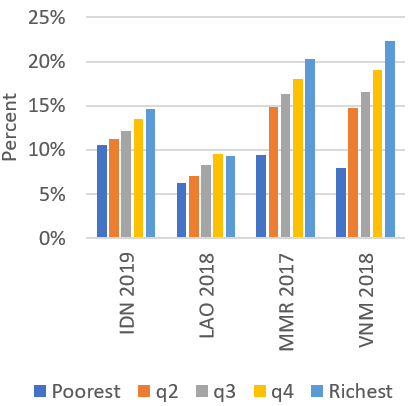

Public vs. Private Education and Equity Issues

EAP features a dual education system: a public system and a vibrant shadow private sector focused primarily on exam performance. As the next chart shows, parents spend a lot on supplementary tutoring in Vietnam and Myanmar. This is highly inequitable, and it also reduces parental motivation for demanding teacher accountability in public schools. The result is an equilibrium with two parallel systems and little demand or promise for improvement in the public system.

Share of households that pay for tutoring (among households with positive expenditure on education) |

Household tutoring expenditure as a share of total education expenditure |

Source: https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/eap/publication/fixing-the-foundation

Breaking the Cycle: Recommendations for Reform

In line with the WDR 2018 and evidence that has accumulated since its publication, Fixing the Foundation suggests four options:

(1) Prioritize effective outreach about the problem (and solutions): Education systems that have successfully implemented difficult reforms—such as Ecuador, Karnataka (India), and Sobral (Brazil)—have often used information strategically to draw attention to the state of education, and garner support for reforms from the broader community.

(2) Build strong coalitions and teams: Long chains of implementation and decision making at multiple stages—within the political sphere, bureaucracy, community and teachers—create room for information gaps and differing motivations. Reforms in Indonesia and Delhi highlight the importance of building coalitions between and across the political chain, bureaucracy and community. Building competent, motivated and stable teams is vital for implementing reforms successfully and making them politically sustainable.

(3) Buy out vested interests: This may be necessary to weaken resistance to reforms. In Indonesia, teachers who agreed to the redeployment and recertification policy received salary increases; others were allowed to opt out, but they had to forgo the salary increase.

(4) Implement and adapt: Successful reforms are often rolled out in a phased manner, which helps address initial flaws, garner wider buy-in and ensure their political sustainability.

Join the Conversation