The entry and exit of firms in the private sector, so-called “firm turnover,” can be an indication of a healthy market, if that means scarce resources are re-allocated from less to more productive firms. Such churning can be substantial in dynamic economies; in the U.S, for instance, according to recent work by the Brookings Institution, “… one new business is born about every minute, while another one fails every eighty seconds.”

[1] Underneath this churning is substantial re-allocation of resources across firms and sector of the economy, with consequential implications for overall productivity growth. As long as exit is tied to productivity, in the sense that the less productive firms are the ones exiting the market, a measure of firm exit could capture the pattern of business dynamism in an economy. However, in the absence of well-functioning markets, firms’ exit from the market can reflect adverse conditions that do not allow otherwise viable, often young, businesses to survive.

What are the patterns of firm exit, and under what conditions do firms leave the market? To date, this question has largely been confined to high-income and only select developing economies. In a recent working paper, we put forth a methodology to provide estimates of firm exit and job loss, as well as to analyze the conditions under which firms exit the market for a large set of developing countries. The study was conducted using data from the World Bank Group’s Enterprise Surveys in 47 developing economies where the surveys have been conducted more than one round.

Here is a brief summary of our findings:

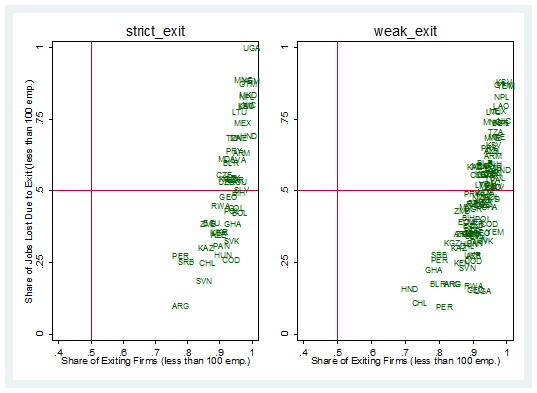

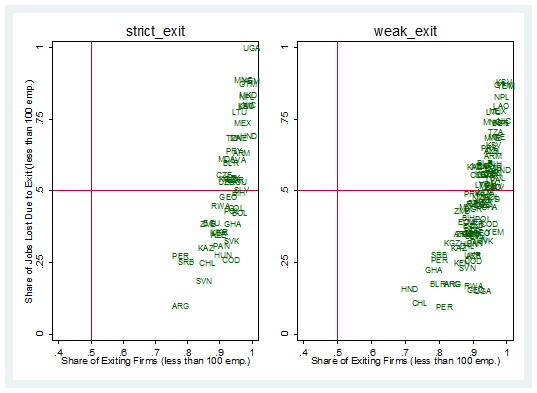

Figure 1: Job Loss and Firm Exit Rates, Relative Share of SMEs (fewer than 100 employees)

These findings can have important policy implications. The nature of private sector competition matters. Young firms, in particular, face a high risk of exiting the market. Small firms also face a higher risk, but this effect goes away after productivity is taken into account. In light of the notable risks for young firms, policy actions should focus on addressing market failures, especially ones relevant to the risk of market exit, including limited access to bank financing, the assurances of more complex legal structures, and markets for foreign ownership.

What are the patterns of firm exit, and under what conditions do firms leave the market? To date, this question has largely been confined to high-income and only select developing economies. In a recent working paper, we put forth a methodology to provide estimates of firm exit and job loss, as well as to analyze the conditions under which firms exit the market for a large set of developing countries. The study was conducted using data from the World Bank Group’s Enterprise Surveys in 47 developing economies where the surveys have been conducted more than one round.

Here is a brief summary of our findings:

- We estimate that 3.7 to 5.4 percent of incumbent firms exit the market annually. We use a necessarily conservative definition to arrive at our estimate and treat these estimates as baseline indicators for firm exit.

- Productivity is strongly correlated with firm exit, with less productive firms more likely to exit. What is more, firms in markets with highly productive competitors are more likely to exit.

- Nevertheless, the greater the number of competitors the less the likelihood of exit, which is a bit surprising, and perhaps a sign of static market competition and thus low market churn via firm exit (and likely low entry). Together, this evidence indicates that large numbers of competitors in a static market can shelter firms from market churning effects, while dynamic and productive markets have an opposite effect as indicated by higher rates of firm exit.

- Not surprisingly, we also find that young firms are more at risk of exiting the market. Small firms are more likely to cease operations in our estimation; but after taking their productivity into account, firm size does not have a significant effect. This means that smaller firms do not face a significantly higher risk of exiting the market if they have equivalent productivity levels as their larger competitors.

- Further, firms with bank financing face a lower risk of exit, as do firms with limited liability, and foreign ownership

- Firms that face lower barriers to entry, as measured by the Doing Business project’s Starting a Business indicator, do face a significantly higher risk of exiting the market. Moreover, where there are more market entrants – indicated by the number of new firms per 1,000 people – there is also a significantly higher likelihood that firms exit the market.

- We estimate that the exit of 3.7 to 5.4 percent firms every year results in an annual job “loss” of between 2.9 and 4.2 percent each year. SMEs (firms with fewer than 100 employees) account for the vast majority of firms exiting the market, but the same is not necessarily true for job losses.

These findings can have important policy implications. The nature of private sector competition matters. Young firms, in particular, face a high risk of exiting the market. Small firms also face a higher risk, but this effect goes away after productivity is taken into account. In light of the notable risks for young firms, policy actions should focus on addressing market failures, especially ones relevant to the risk of market exit, including limited access to bank financing, the assurances of more complex legal structures, and markets for foreign ownership.

--------------------------------------------------

Join the Conversation