On her daily walk down the muddy road that connects her home with school, Beatriz would sing a cumbia and dream of becoming a professional dancer. However, she would soon find out that her aspirations were short lived. At the age of 14, Beatriz got pregnant and never went back to school. In the six years following her pregnancy, she struggled with an unstable and low-paid job, cleaning rich houses in Guatemala City. By the age of 20, without minimum skills and a secure job, Beatriz had little control over her life and a murky picture of her future loomed.

About 150 miles away in El Salvador is Miguel, who has always admired his big brother Gus. The eight-year difference between them made Gus somewhat of a father figure to Miguel. At the age of 15, Gus quit school and started working as a “delivery boy” for a local gang in San Salvador. Miguel would ask his brother for a chance in the business, but Gus refused, arguing that it would ruin his life. One day, that bitter discussion would be the last interaction between the two brothers, as Gus was shot to death by a rival gang member a few days later.

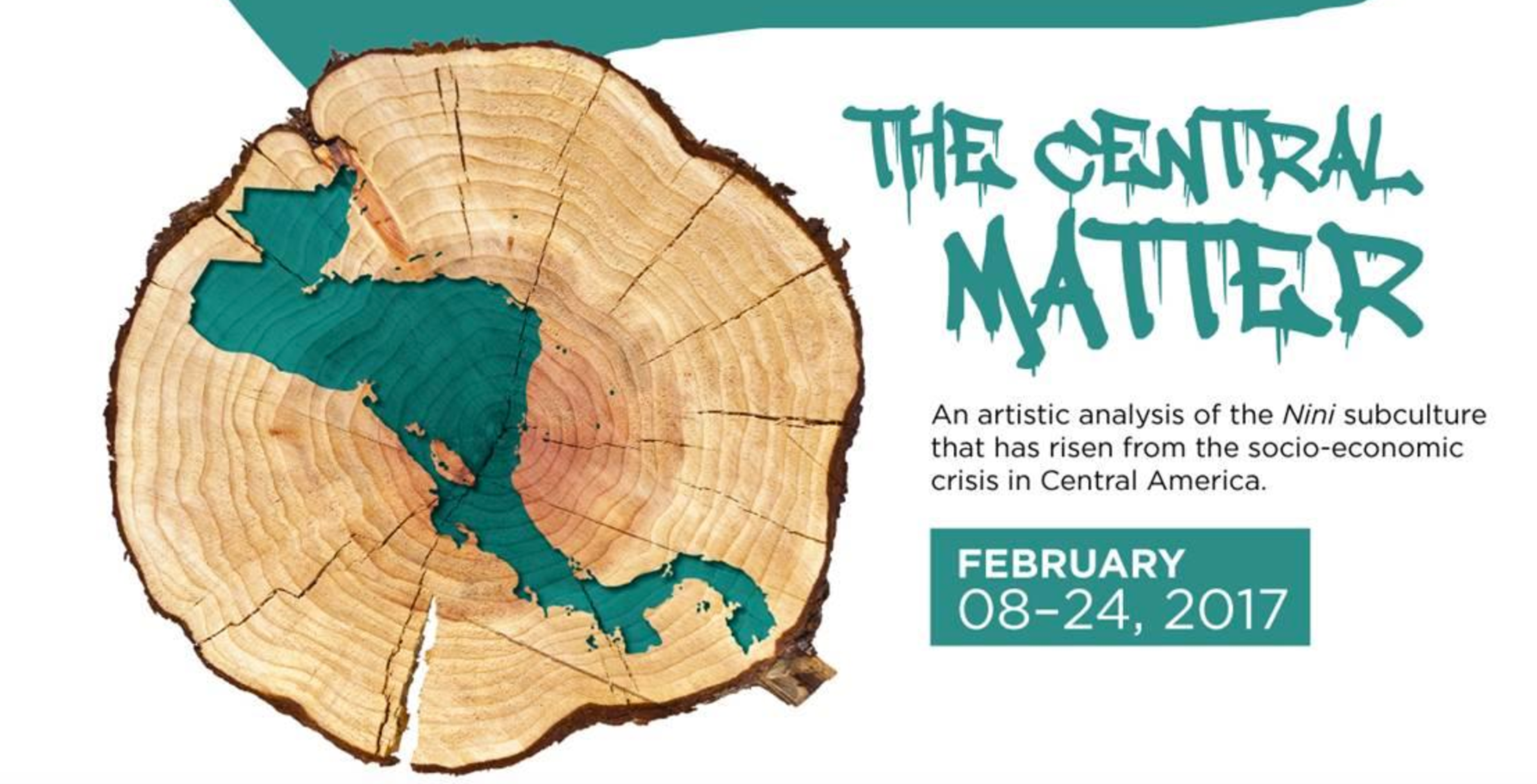

These two scenarios come from the theatrical performance of Héroes Perdidos (Lost Heroes) part of the art exhibition “The Central Matter” showcased throughout February at the World Bank Headquarters in Washington D.C. Unfortunately, the lives of Beatriz and Gus are not extraordinary cases amongst youths in Guatemala and El Salvador. A fifth of teenagers are already mothers in Central America and murder rates in this region are the highest on earth, which harms youths more than it does any other group.

The widespread hopelessness amongst youths in Central America, with 1 in 3 out of school and out of work, has created a subculture characterized by violence, drug abuse and attempts to migrate to the U.S. via Mexico. The art exhibition “The Central Matter” portrays Central American youths’ frustration, despair, and lack of opportunities. Through original photographs, paintings, sculptures and video art by Central American artists, this exhibition aims to create awareness of the desolation amongst the many youths in the region.

The first step towards a solution to the lack of opportunities amongst Central America’s youth is to acknowledge the problem and have a clear understanding of its causes. The lack of opportunities for youths in Central America is an outcome of income disparities. Inequalities and social injustice are built early in life as it is portrayed by “Las flores del mal,” an installation by Inés Verdugo (Guatemala).

Children in poor households do not receive the nutrition and early stimulation needed to succeed in school. In addition, those children go to poor schools that fail to compensate for the adverse initial conditions, increasing inequalities further. These same kids drop out of secondary school without minimum cognitive and socio-emotional skills. Then as teenagers, they engage in risky behavior, like drug consumption and unprotected sex. Some of them, having little to no choice, participate in criminal activities.

As mentioned in our report, Out of School and Out of Work: Risk and Opportunities for Latin America’s Ninis, governments in Central America and the international community should work together to put in place effective policies to help the youth in the region. Prevention is, by far, the most efficient strategy.

Starting early by providing the appropriate nutrition and stimulation to infants would yield a huge return in the long run. Providing incentives to have the best teachers serving the poorest communities, would help to improve social inequalities. For those in secondary school, there are successful interventions based on cognitive behavioral therapy that are currently being evaluated in Mexico; they could be easily adapted to the Central America context. Short-term training programs with a strong link to the private sector and with modules to improve socio-emotional skills have been proven to increase employability among those who dropped out without the minimum basic skills.

However, in the short term, none of these effective policies would change the harsh reality that millions of youth face in Central America. For many of them the only viable option is to leave. They take the little they have, cross the border into Mexico, jump in a train called “La Bestia” (The Beast), and travel a long and often inhumane journey through Mexico to the U.S. This journey is portrayed in “Opciones para escapar a un lado más seguro,” a digital print by artist Ronald Morán.

While Central America has a plethora of talented artists who create beautiful works of the region’s many riches, the purpose of The Central Matter is to expose a reality that is often ignored or unspoken. By creating awareness of the Nini phenomenon, and by sharing our report’s findings and policy recommendations, we hope to inspire a movement that contributes to providing opportunities for Central America’s youth. Only then will the region be able to take full advantage of the possibilities for economic development and poverty reduction.

Find out more about World Bank Group education on our website and on Twitter .

Join the Conversation