In the recent READ 2 Trust Fund Newsletter, I wrote about Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4, which is the United Nation’s main global goal for education. A key indicator for monitoring progress towards SDG 4 requires countries to report on the “ proportion of children and young people in Grade 2 or 3, at the end of primary education, and at the end of lower secondary education to achieve at least a minimum proficiency level in reading and mathematics”. For many countries, a key measure of proficiency at the end of lower secondary education is the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment ( PISA). Historically, however, few lower-income countries have participated in this exercise, which means they lack an international benchmark for how their students are performing at what is essentially the end of compulsory schooling.

As Jaime Saavedra, Senior Director of the World Bank’s Education Global Practice, highlighted in his recent blog, Measuring learning to avoid “flying blind,” December 11, 2018 marked an important milestone for the education community, with the release of results for seven lower-income countries -- Cambodia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Paraguay, Senegal and Zambia – that had participated in the PISA for Development ( PISA-D) pilot. Launched in 2014, this one-off pilot, spanning six years, aimed to make the PISA assessment more accessible to lower-income countries. The World Bank’s READ Trust Fund financed a number of key PISA-D activities, including technical workshops to inform the design of the instruments, high-level reports on lessons learned from existing cross-national assessments, and capacity needs analyses and capacity building plans for the participating countries.

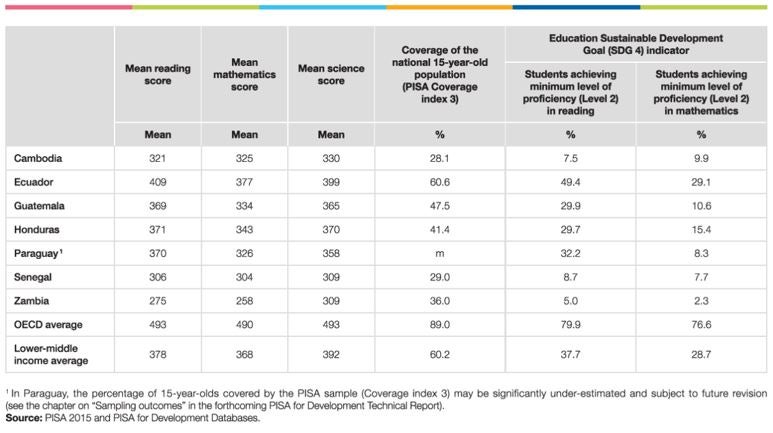

For the seven countries that participated in the pilot, PISA-D is important because it provides them, for the first time, with internationally comparable data on learning levels at the end of their compulsory schooling. The results, as shown below, are very disturbing.

Snapshot of performance in reading, mathematics and science

On average, only 43 percent of all 15-year-olds in these countries were enrolled in at least grade 7 by age 15 and therefore eligible to sit the PISA-D test, compared to the OECD average of 89 percent. The remaining 15-year-olds were either in grades below 7 or out of school. Average performance in reading ranged from 275 on the PISA scale for Zambia to 409 for Ecuador, well below the OECD average score of 493. Average performance in math and science was no better. The data offer much food for thought for the individual countries involved and hopefully will help them design better policies and practices to improve learning outcomes going forward.

The longer-term importance of PISA-D, however, lies in the removal of key barriers to lower-income country participation in PISA in general. I’ll mention three here.

First, PISA-D was specifically designed with the information needs of lower-income countries in mind. For example, the PISA-D cognitive instruments used questions from the PISA item pool that are more suited to students in developing economies and the background questionnaire was redesigned to include questions suited to the economic and social conditions of lower-income countries. These innovations were done in a way that still let participating countries place their results on the official PISA scale.

Second, PISA-D was specifically designed with the technical capacity requirements of lower-income countries in mind. This involved supporting participating countries to carry out an upfront capacity needs assessment to determine the kinds of technical and other support needed to carry out the assessment. The results of this exercise were used to develop a capacity building plan for each country to ensure that its needs were met throughout the entire implementation process. As a result, all of the countries that joined PISA for Development successfully completed the exercise.

Third, PISA-D was specifically designed with the out-of-school populations of countries in mind. The focus on out-of-school youth was particularly important given that many lower-income countries have a sizeable proportion of their 15-year-olds outside the formal school system. The PISA-D pilot included an out-of-school assessment so that these countries could have a better understanding of the learning levels and needs of their 15-year-olds who were no longer enrolled in school.

From 2021 onwards, the instruments and capacity building options developed under PISA-D will be incorporated into the main PISA exercise. Already, many lower-income countries have signed up for PISA 2021, which looks set to be undertaken by over 100 countries. This means that for the first time in the history of PISA a truly diverse set of countries will be able to compare the learning levels of their 15-year-olds, whether in or out of school, at the same time and on the same scale . Individual countries will have access to an unparalleled source of information on the comparative performance of their future citizens to those in countries around the world. For some, this will prove an unpleasant wake-up call. For others, it will provide confirmation that their reforms are on track. Meantime, the international community will gain a much better understanding of the global map of learning and where and how to best target efforts. Certainly, there is still work to be done to improve the value and accessibility of PISA and other international assessments for lower-income countries, but the completion of the PISA-D pilot marks an indisputably significant milestone in that journey.

Want to know more? You can find overall results, national reports, and data for PISA-D here.

Join the Conversation