Power lines coming out from Itaipu Hydroelectric Dam | © Jose Luis Stephens, Shutterstock

Power lines coming out from Itaipu Hydroelectric Dam | © Jose Luis Stephens, Shutterstock

Hydropower has an important role in achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 7 of ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all. It is the largest zero carbon energy source, which provides approximately 16% of electricity worldwide.

In addition, there is an untapped potential of 10,000 TWh per year of undeveloped hydropower, which could bring modern energy services to millions of people. However, while hydropower remains among the lowest-cost sources of electricity globally, developing hydropower also requires a sizeable investment. Therefore, the developing countries’ governments must understand the long-term economic benefits of such investment.

Brazil is an important case study for quantifying the economic benefits of hydropower investment. In the 60s and the 70s decades of the last century, the country went through rapid industrialization, which required significant infrastructure investments. Since the 1970s, Brazil has made the energy sector a central element of its economy, and hydroelectric plants have become the solution for electricity production. This decade saw significant investment in hydropower, involving the construction of the world’s largest hydropower plants such as Itaipu, Tucuruí, and the Paulo Afonso Hydroelectric Complex.

Although the financial crisis of the 1980s eroded the government investment capacity and led to a long period of stagnation, investment in hydropower grew again in the 2000s. Between 1970 to 2010, total electricity generation increased tenfold, with hydropower accounting for approximately 88% of total consumption (Figure 1).

Advances in the electrification process accompanied hydropower development. Residential electrification rates rose sharply, with household access increasing from approximately 48% to 99%, covering three-quarters of the country’s area during the same period (Figure 2).

To find the answer, the World Bank study Electricity Access and Structural Transformation: Evidence from Brazil's Electrification developed a general equilibrium model with unbalanced economic growth and later analyzed it quantitatively based on Brazil’s data. The salient feature of the model is the introduction of electric power infrastructure chosen by an optimizing government. This infrastructure increases the productivity of firms’ investment in private energy-using capital. It also reduces firms’ fixed costs of operation through, e.g., a lower need for supporting equipment like small diesel-fired generators. Moreover, the improvements in electricity access are conducive to technological progress such as, e.g., the adoption of electric irrigation pumps.

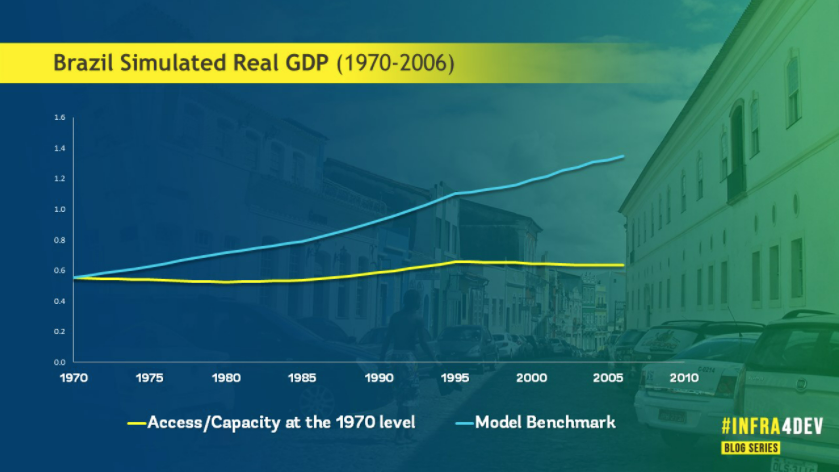

In the benchmark scenario of model simulations, we mimicked the actual investment in electricity grid access and generation capacity. We then compared this case with a hypothetical scenario where Brazil’s economy follows the same baseline except for its electricity access and generation capacity staying at the 1970s level. While somewhat extreme, this case allows us to quantify the extent to which power infrastructure has contributed to the country’s economic development.

The results of such an exercise are striking. In the early years, the simulated gross value added (GVA) is roughly at the same level in both scenarios. However, absent power infrastructure, there is a drastic output decline relative to the benchmark scenario across all sectors of Brazil’s economy in the following years (Figure 3).

The industry sector is particularly affected, with the simulated GVA 37.55% lower in 2006 than the benchmark case. Production in agriculture and services would have decreased by 20.64% and 22.92% compared to the model benchmark, respectively (Figure 4). All in all, constraining electricity availability has a significant impact on welfare, reducing GDP by 35.96%.

Besides direct growth effects, we find that power infrastructure investments have also led to the changing structure of Brazil’s economy. In the absence of power infrastructure formation, the share of the energy-intensive industry sector would have been, on average, 1.73 percentage points lower, whereas the ones of services and agriculture are 1.67 and 0.06 higher, respectively. While these relative effects may appear smaller due to offsetting nature of various general equilibrium effects, they nonetheless explain at least one-fifth of the observed structural transformation process (i.e., economy’s transition from agriculture to industry and industry to services).

Other studies have also found that power infrastructure investments resulted in long-term improvements in human development, while locations suitable for hydropower generation experienced improvements in crop yields, thus reducing deforestation.

An important final observation is that building hydropower plants alone wouldn’t have led to long-term gains without electrification policies. Another recent study has found that while Brazilian municipalities that built hydropower plants had experienced larger local economic gains than otherwise similar municipalities with hydropower projects planned but not yet built, these were short-lived. That is the long-term economy-wide effects of electricity availability, such as lower operational costs and higher productivity are considerably larger than local economic effects associated with construction of large-scale projects like hydropower plants.

#Infra4Dev is a blog series that showcases recent World Bank economic research to explore how Infrastructure is critical for development.

Subscribe here to stay up to date with the latest Energy blogs.

Previous Infra4Dev blogs:

How Does Infrastructure Investment Promote Economic Development in Fragile Regions of Africa?

The effectiveness of infrastructure investment as a fiscal stimulus: What we’ve learned

If you build it, they will come: Lessons from the first decade of electric vehicles

Can policy measures reduce the environmental impact of urban passenger transport?

How can we explain the rise in transport emissions… and what can we do about it?

Join the Conversation